A Strategy for Belonging - Fighting fading identities in Norwegian Coastspace

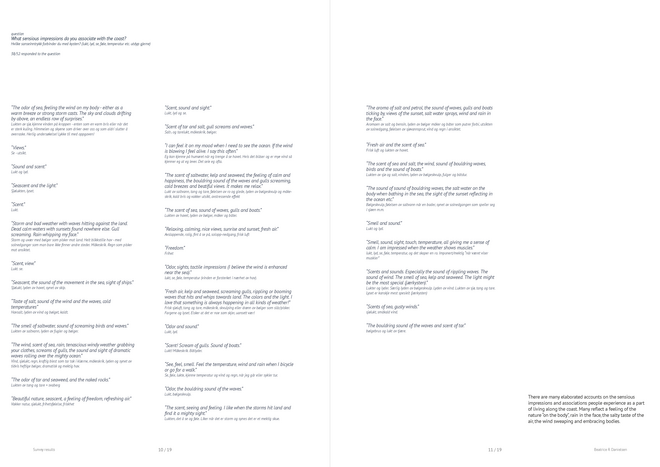

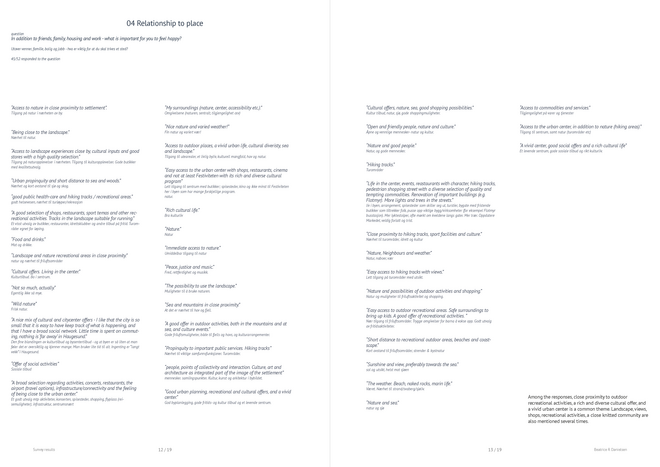

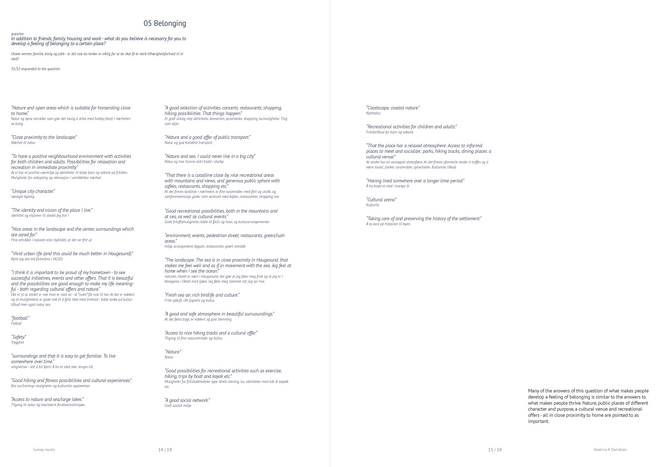

What does it mean to belong, and how does our physical environment affect a feeling of belonging? These were central questions in my research on the Norwegian southwest coastspace.

Throughout my thesis, the drawing "Sjøsprøyt" by Harald Sohlberg has been one of my greatest inspirations. I find the way he has managed to depict not only a landscape, but an atmosphere – a way of being human in the dramatic meeting of sea and land. In the drawing I see, and recognize, the feeling of standing on the west coast when the waves are hitting land and the rain is pouring down. It is an image of constant movement, and the calm feeling looking at the endless horizon, of longing towards the sea and dependency of what is there.

0.00 On Belonging, Identity and Landscape

In my research on the southwest coastspace I found that belonging, identity and landscape are closely interlinked. These three concepts has been central throughout my project, and my working hypothesis has been that a feeling of belonging can be strengthened by using the characteristics and attributes of the landscape to unfold the identity of the coast settlements.

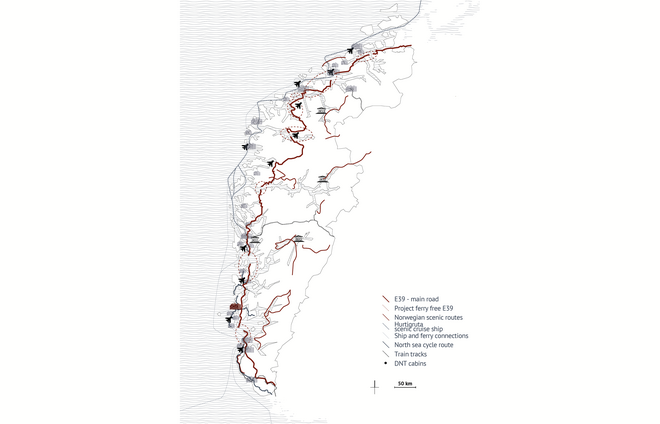

1.00 The region of southwest coastspace

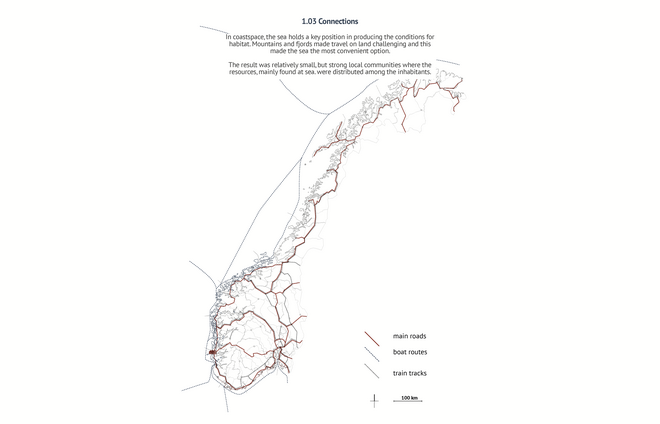

A Norwegian region is defined by the scholars Jones and Olwig, as more than just the visual appearances. It is defined as “socially constructed through the identification of certain characteristics seen as particular to that region, such as customs, language or dialect, a way of life, or features of the physical environment”. The result is very different sets of conditions for settlement in the different regions.

One of the most important characteristics is the coast and the key position it has in producing the conditions for habitat. Svein Hatløy argues the coastal settlements are conscious and unconscious orientated towards the sea. This orientation is not only a result of the familiar view of an undisturbed horizon between the sky and the sea, it is also a result of the possibilities found both beyond, above and underneath it.

The connection between landscape, identity and society is strong and many faceted, especially the impact on the economic sector. Norwegian settlement, growth and fortune is to a large extent a result of access to natural resources, such as fishing, shipping and petroleum. The resources and the way they are managed, has built a stable foundation for the Norwegian social democracy and the welfare state. The Norwegian society, therefore, has good reasons to feel a strong connection, dependency and appreciation towards the landscape.

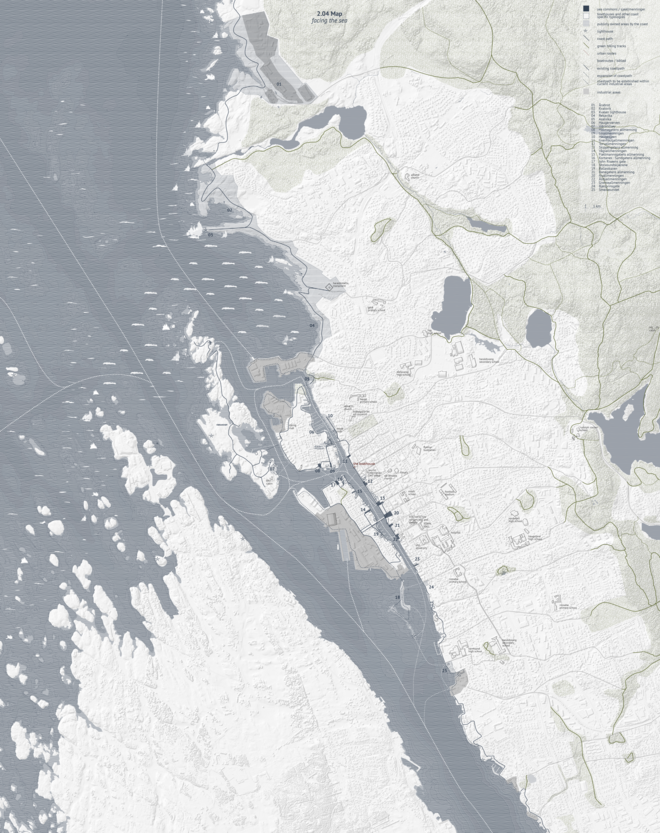

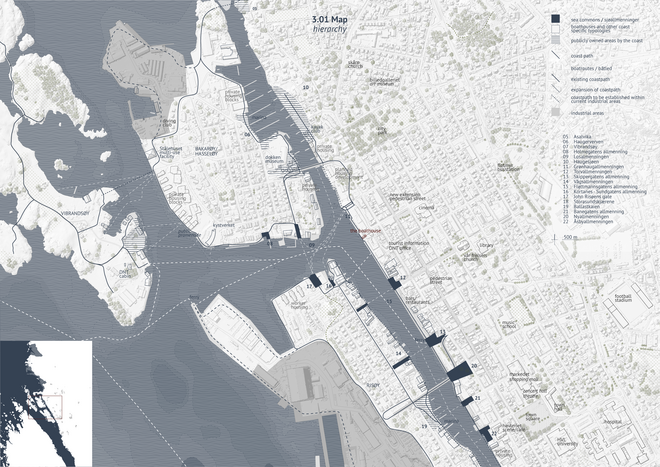

2.00 A new network of encounters between sea and settlement

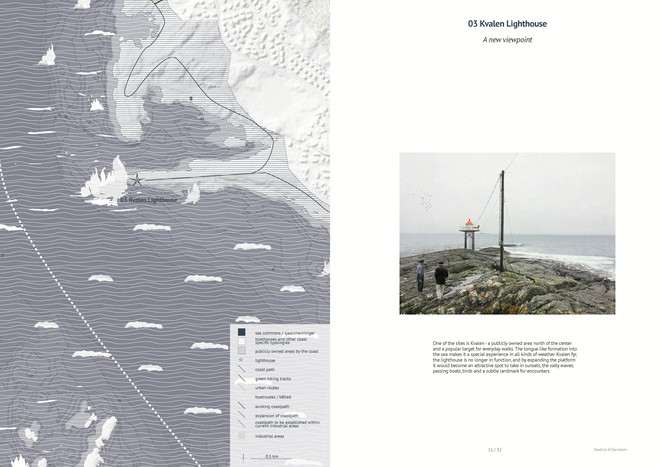

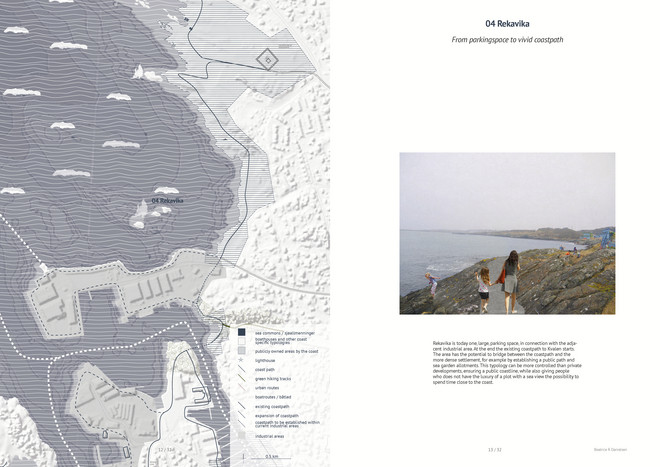

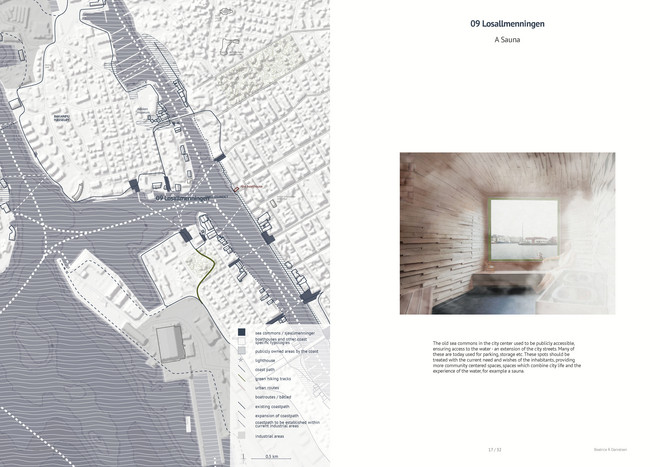

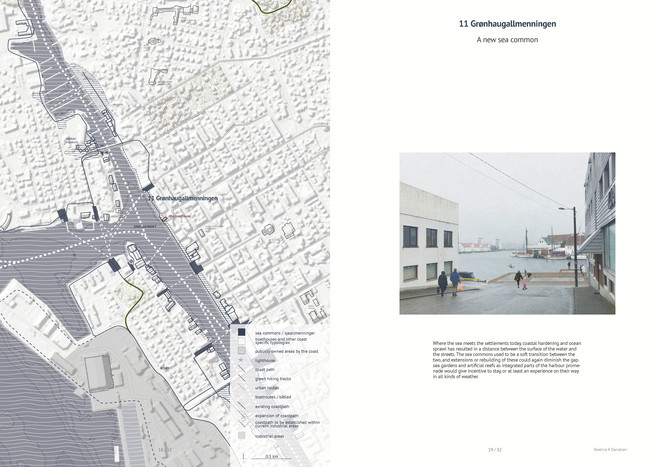

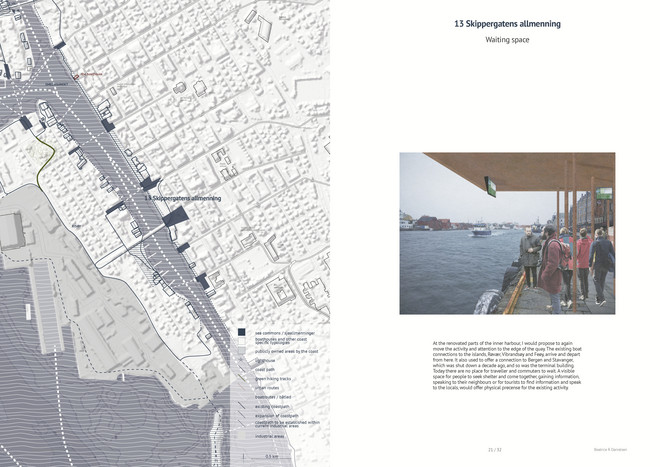

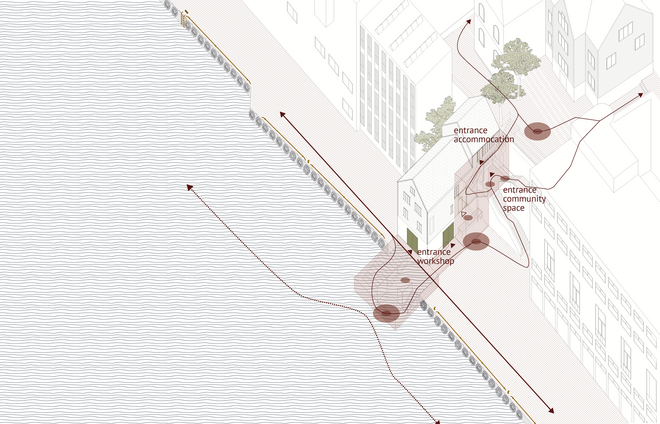

The sites in the network comprise previous sea commons - publicly owned places in the settlement which used to work as points of connection between land and sea, and other publicly-owned areas by the coast, in addition to boathouses and lighthouse.

The sites in the network can function as independent points of encounters, however, it should also be an alternative to walk along the coast, visiting several of the sites on the way. This new coast path would comprise wilder landscapes in the norths, a path already well established, through the inner harbour and out to the neighbourhoods in the south.

The integration of the city islands on the walk by new permanent connections, and the islands through increased ferry connections and public mooring places will result in a diverse coast path - which could even be imagined established along the entire coast.

The network also relates to the existing urban fabric, knitting sea and settlement together, taking in to account the existing institutions, cultural offers and invites the associations to be a part of the development of the activities promoted by the new network.

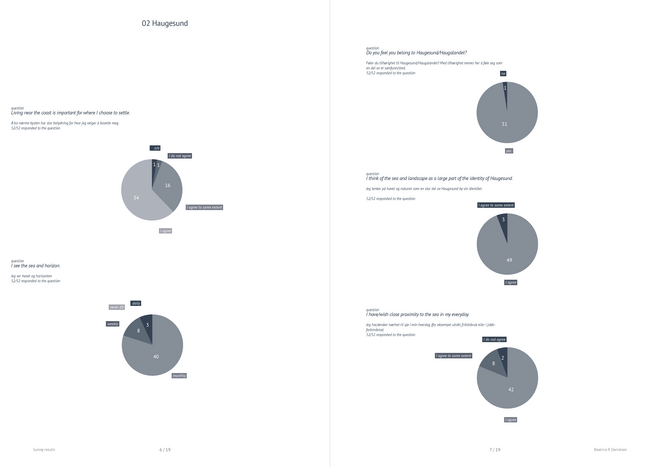

Haugesund is a city of 40.000 inhabitants with a steady growth, on the southwest coast of Norway. Already in the name, we find the first reference to the landscape. Sund or strait, refers to the city’s location in Karmsundet, with Karmøy on the other side of the strait protecting the city from the north sea. The city has rich access to recreational areas, such as the coast landscape, islands, and the mountains, and the resources found at sea has been key for the settlement to sustain a living.

The area has a long history of settlement, although the city itself is young, only established in 1854. Idar H. Pedersen describes the city’s reliance on the sea with the words: “rapid changes the city has experienced, the city has played with the ocean and the ocean is a petulant teammate, it takes – and gives plenty back, but you never know when”.

This leaves a new map of Haugesund, of a settlement once again facing the sea. The narrow belt of habitance in close relationship with the mountainous landscape - the backbone of the settlement, and the vast sea and island communities.

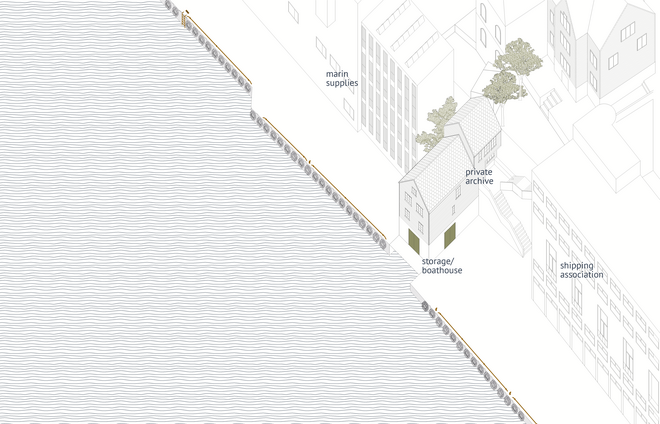

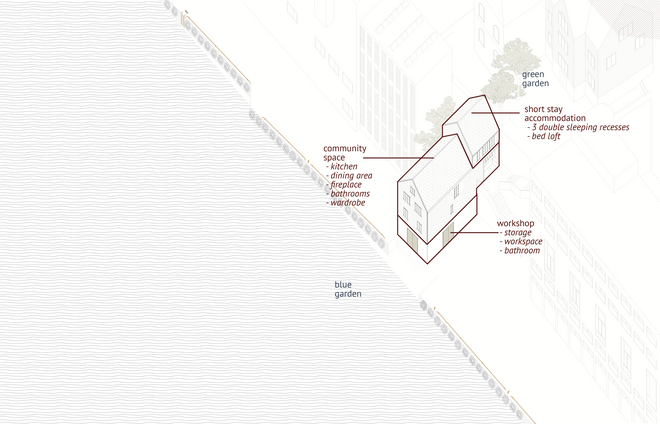

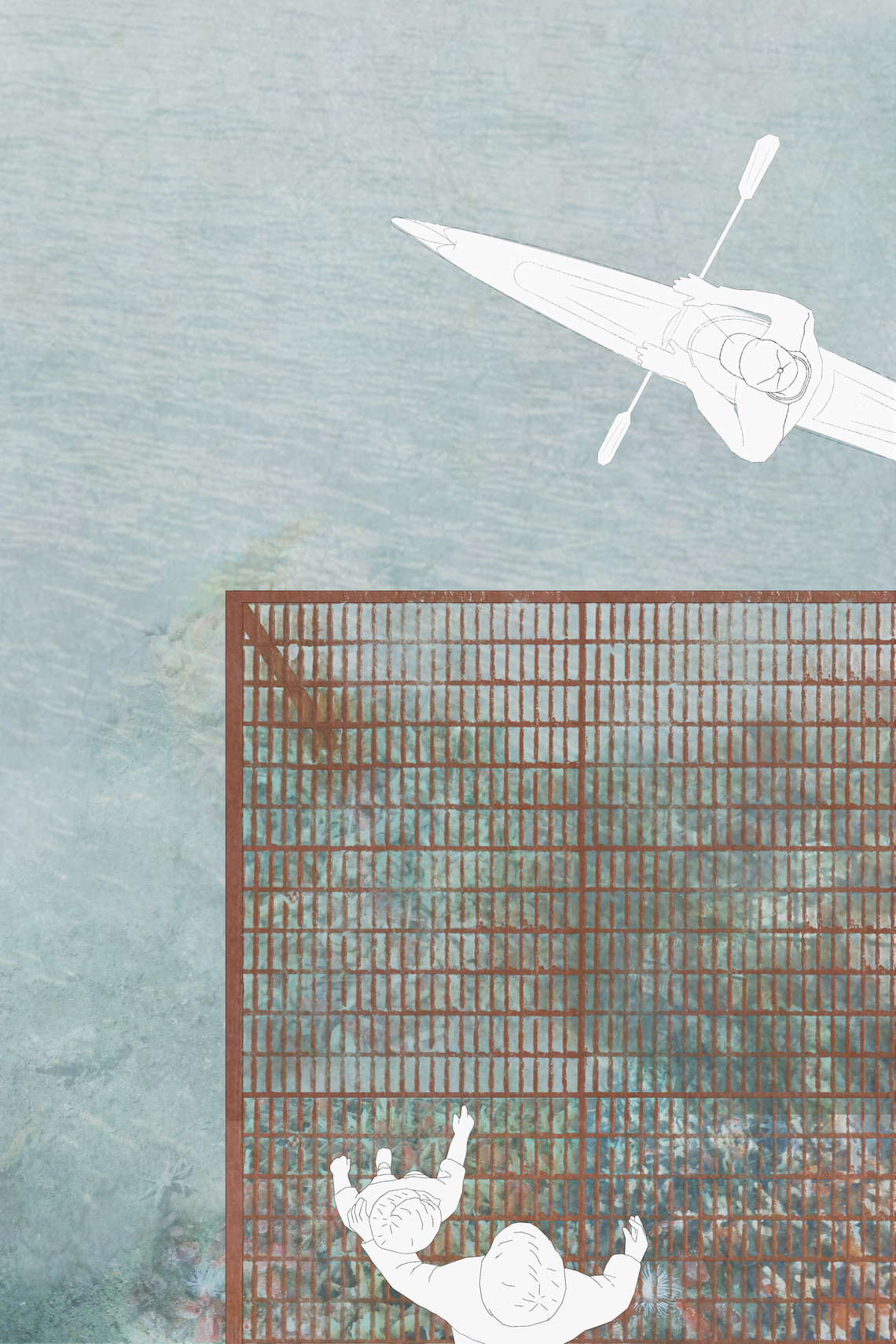

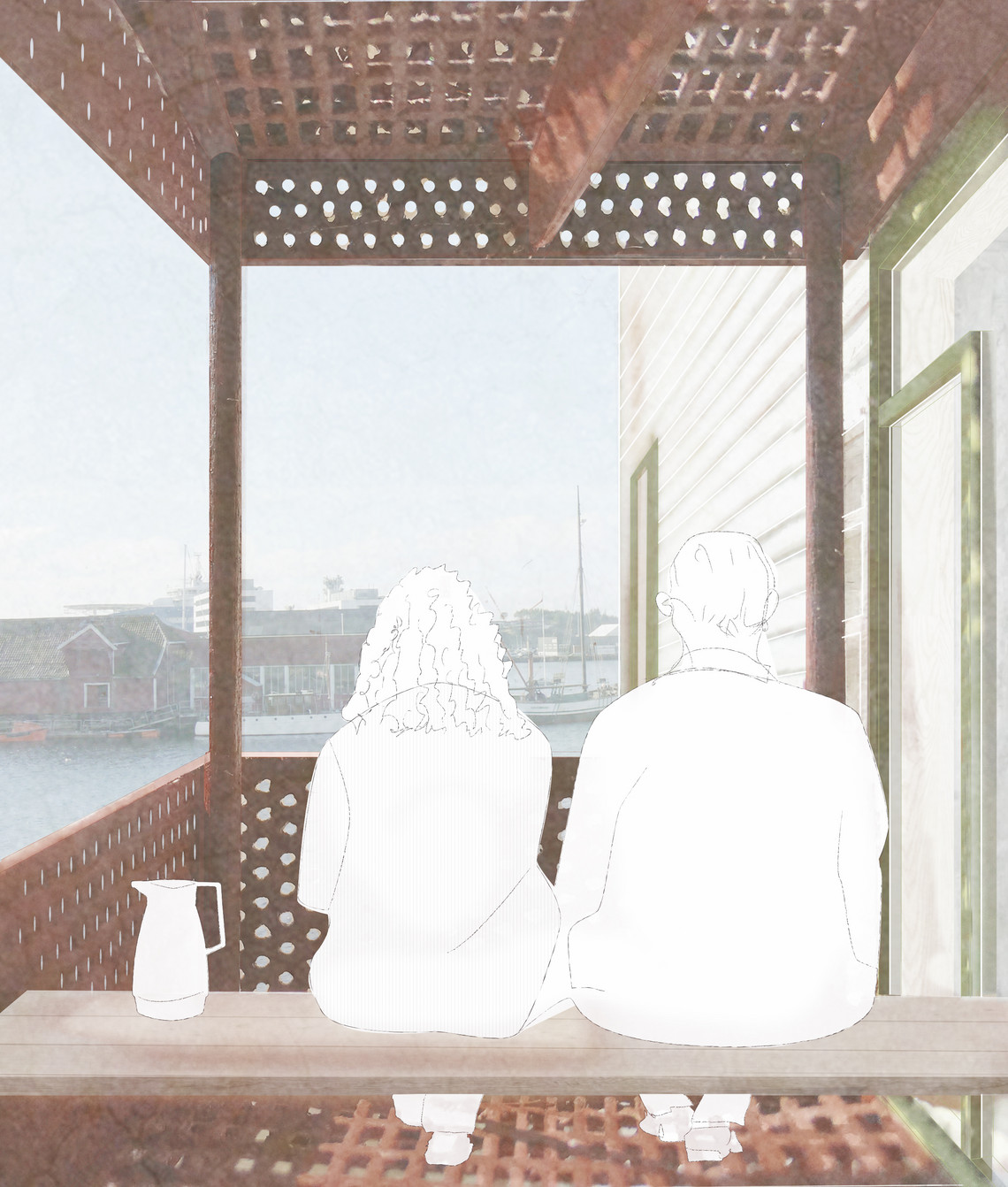

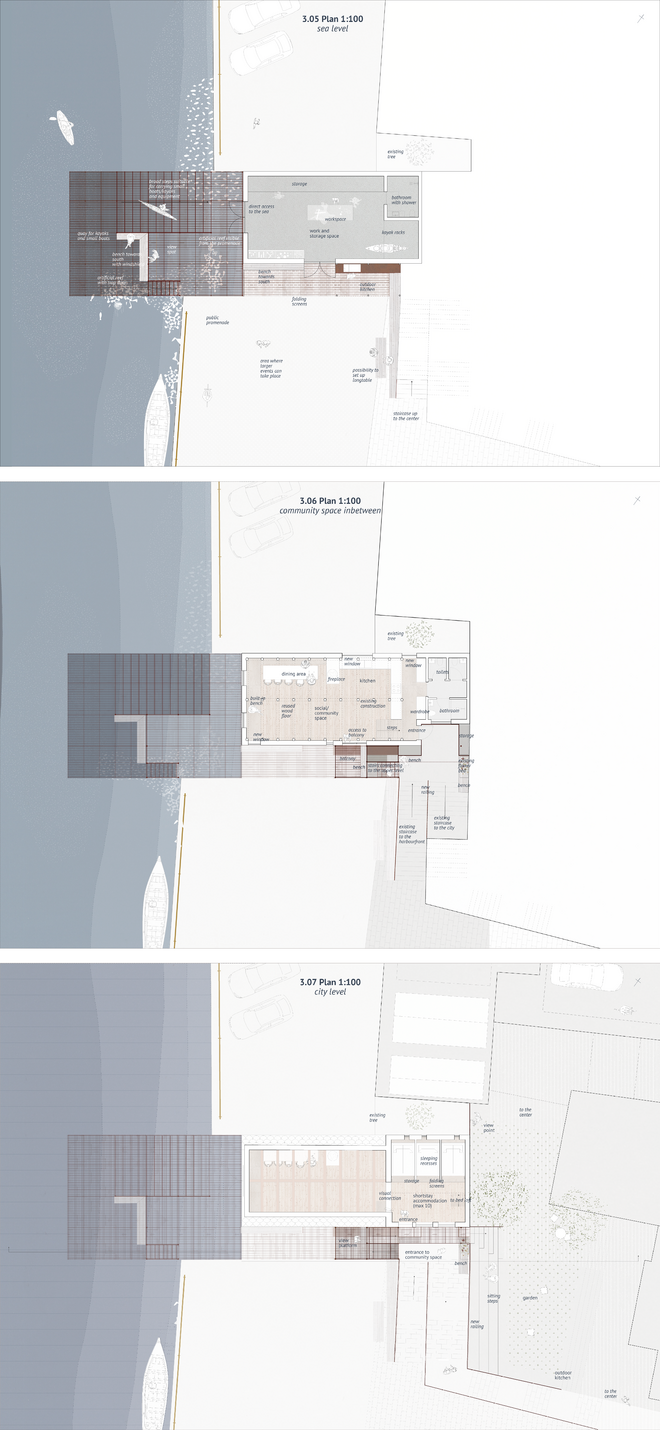

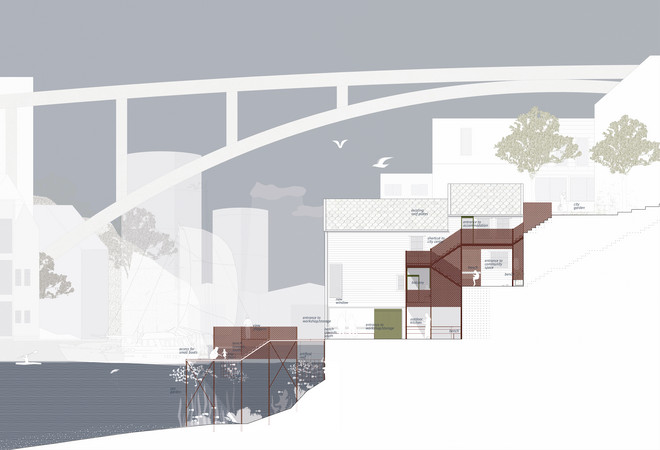

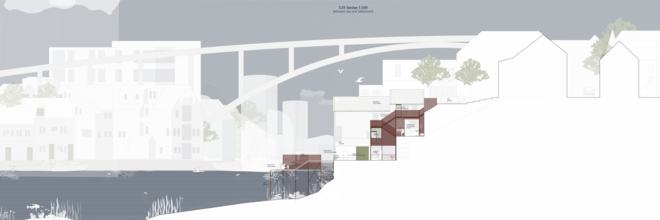

3.00 A new place for encounters in the harbour

The project is a transformation and addition of one of the last boathouses in this area of Haugesund. The intention is to make the connection between the urban center of the settlement, through the inner harbour, down to the water strong again. The transformed boathouse will be a place of encounter between land and sea, shared by the local community with visitors from the rest of the coast region, and other tourists. As one of the last boathouses it will continue the physical storytelling of the city, as a typology functioning as a hinge between land and sea.

My project can be summed up in very simple words – reconnecting Haugesund to the water. However it is also about more complex intentions, I believe the vision to strengthen a feeling of belonging can happen by emphasizing the relationship between settlement and sea and by creating places where this identity becomes a present part of the everyday life and where it can continue to develop on the grounds of the very reason for settlement. Haugesund will always be characterized by the meeting between land and sea, although the way this encounter happens will continue to change, along with the inhabitants and community’s way of acting in these conditions. From first and foremost being a landscape of resources, it is today an important recreational arena and tourist attraction. The landscape Haugesund is located in is more than merely its visual character, the landscape is the very foundation for the city’s existence. However, if the growth and expansion happens at expense of the qualities at place, if Haugesund looses its coastline and close proximity to the landscape, will it continue to be an attractive place to settle? Will the inhabitants no longer feel belonging to the place?

The landscape is the shared basis for the coast communities, and if it is to continue to be so, it needs to be a part of the urban hierarchy.

In this strategy, I have worked to extend the understanding of identity in public places by not only discussing it as appearance and function, but also through the complex social structures and behaviours it produces and accommodate. I believe that if we produce public places which act with the characteristics found, both in the physical surroundings and in the societal structure, places which not only offer a place to stay, but intrinsically lead to an understanding of the surroundings and society in which they are located, a feeling of belonging could be strengthened.

The importance of the qualities of place is increasing, as we are freer to settle according to other preferences than those of necessity. If these places by then have become identityless and do not have something else to offer their inhabitants, what is their future?

Det Kongelige Akademi understøtter FN’s verdensmål

Siden 2017 har Det Kongelige Akademi arbejdet med FN’s verdensmål. Det afspejler sig i forskning, undervisning og afgangsprojekter. Dette projekt har forholdt sig til følgende FN-mål