AS ABOVE SO BELOW

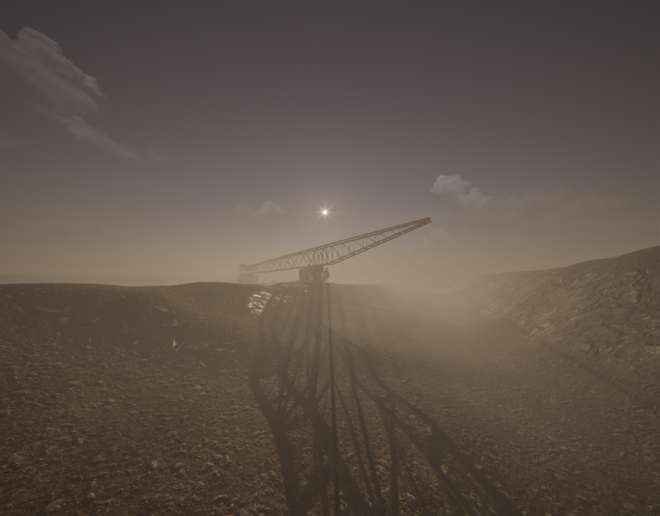

This project addresses the middle ground between spatial and temporal forces in eastern Germany. After lignite coal mining strips a land of its topography, fertility, and people, what is left to rescue? In a devastated landscape, how do we choose to stay? The project attempts to wrestle with questions of residue and pollution to suggest an alternative future for post-capitalist wastelands.

In the area of Lusatia, in East Germany near the Czech and Polish borders, a significant amount of lignite "brown" coal lies just under the earth's surface. Once providing 40% of East Germany's energy under the GDR, after the collapse of the USSR the mines were bought by Swedish company Vattenfall, and then sold to LEAG (Lausitz Energie Bergbau AG) in 2016, who now employ some 800 miners and engineers in the region.

In 2023, 41.7 million tonnes of lignite were mined in this district. 25% of Germany’s energy still comes from brown coal, and Germany is still the world leader in lignite extraction.

The “Energiewende” or Energy Transition Plan published by Angela Merkel in 2003 mandated a significant reduction in German CO2 emissions in alignment with the Paris Accord, demanding that the Republic should heavily regulate, improve the efficiency of, and eventually phase out lignite energy production entirely by 2045. Most lignite mines in the region are projected to close by 2038, but the year shifts constantly as LEAG and several miners unions fight to keep the industry alive.

Once these mines close, what then? LEAG is legally responsible for rehabilitating and revegetating these devastated landscapes. This is a huge opportunity, but a huge responsibility. Their current proposal aims to cover around 53% in forest, 25% in lakes, 10% agricultural fields, and the remaining 12% willl be roads and tourism infrastructure. They are constructing Europes largest network of artificial lakes, and proposing significant re-engineering of the landscape to ameliorate the acidification, soil liquefaction and erosion brought about by open-pit mining.

As a response to this real-world proposal, my project is a speculative investigation into an alternative future for the ruined post-capitalist landscape of the lignite mining industry in Eastern Germany

"Residues defy scalar expectations. Residue accretion is the principal physical driver of our planetary crisis. And monitoring this accretion constitutes the key method of Anthropocene epistemology: it’s how we know the geological, atmospheric, and biophysical impact of human activity.

In the Anthropocene, residues are the main event."

Gabrielle Hecht: “You can see Apartheid from Space”_Residual Governance_(2023) 34

Turning the mines into artificial lakes is only one answer. These proposed lakes, by themselves, would take 100 years to fill. Water is therefore instead diverted from the nearby Spree river and other aquifers to speed up the process, further inducing drought-like conditions in the region. The newly exposed pyrite in the tailing piles reacts with water, leaching sulphuric acid into the soil and water systems. The lakes, left to themselves, would be as acidic as vinegar (pH of 4 or 5). LEAG has had to devise complex strategies to neutralise the water, including boats that deposit alkaline substances, such as caustic lime and chalk, which increase the pH to around 7.0 and can make the water occasionally look turquoise. These huge, expensive, and Sisyphean efforts to return the landscape to a sort of pre-mining utopia are in whose service? Certainly not the fish. And who will maintain these fragile and newly implemented ecosystems when the money runs out and the mining companies are no longer legally required to? Over 11 billion euros has been spent on landscape engineering since the 1990s. And is tourism —once again turning to profit— the answer to a ravaged post-capitalist landscape?

This project takes its initial jumping off point from the fact that rehabilitating a landscape is a tautology, a moot point. The landscape that once was has fled, any landscape that replaces it will be entirely, unavoidably different. Every tablespoon of fertile topsoil contains ten times more organisms than there are people on the planet. Every hour the f60 machine in a Lusatian mine is capable of digging out 29000m3 of earth, (or around 2 billion tablespoons). If we embrace, acknowledge, and fully take responsibility for the Anthropocene, then we would not attempt reimposition of previous paradigms, we must look for new ways of inhabiting and coexisting with this terra firma that we have shaped with our own hands.

METHODOLOGY

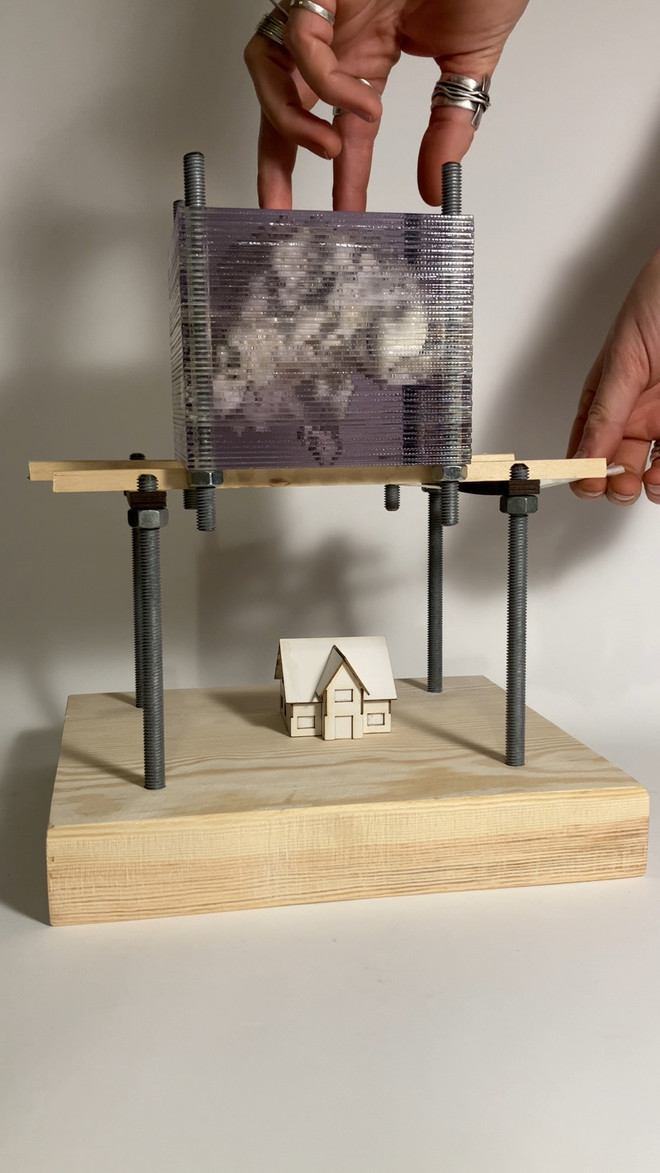

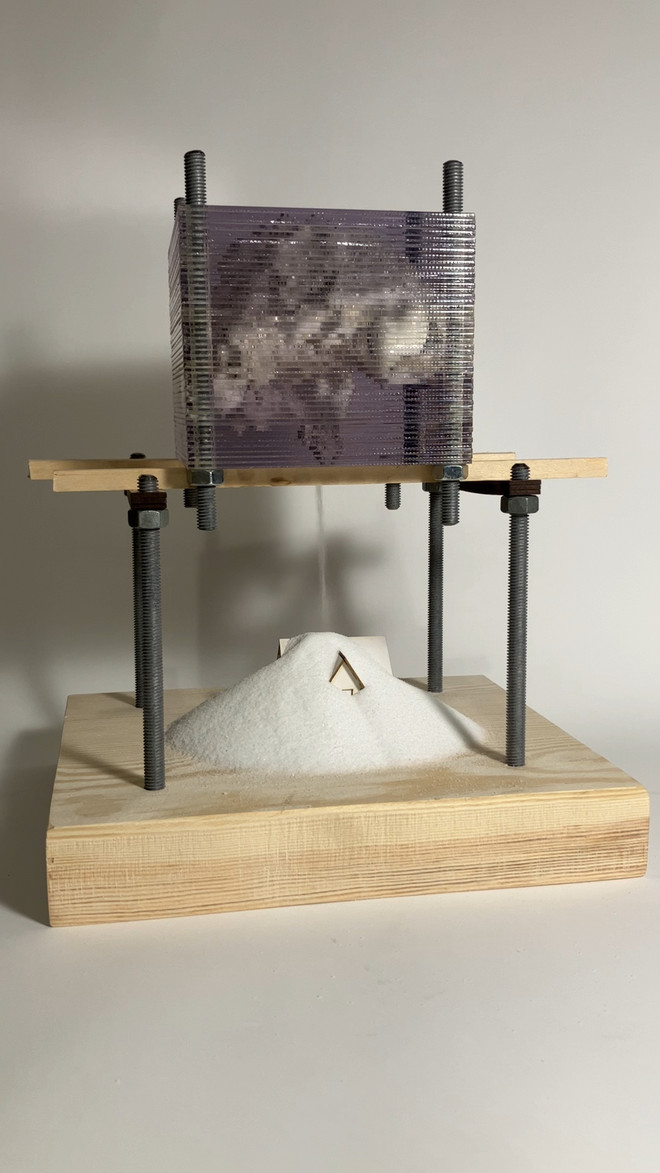

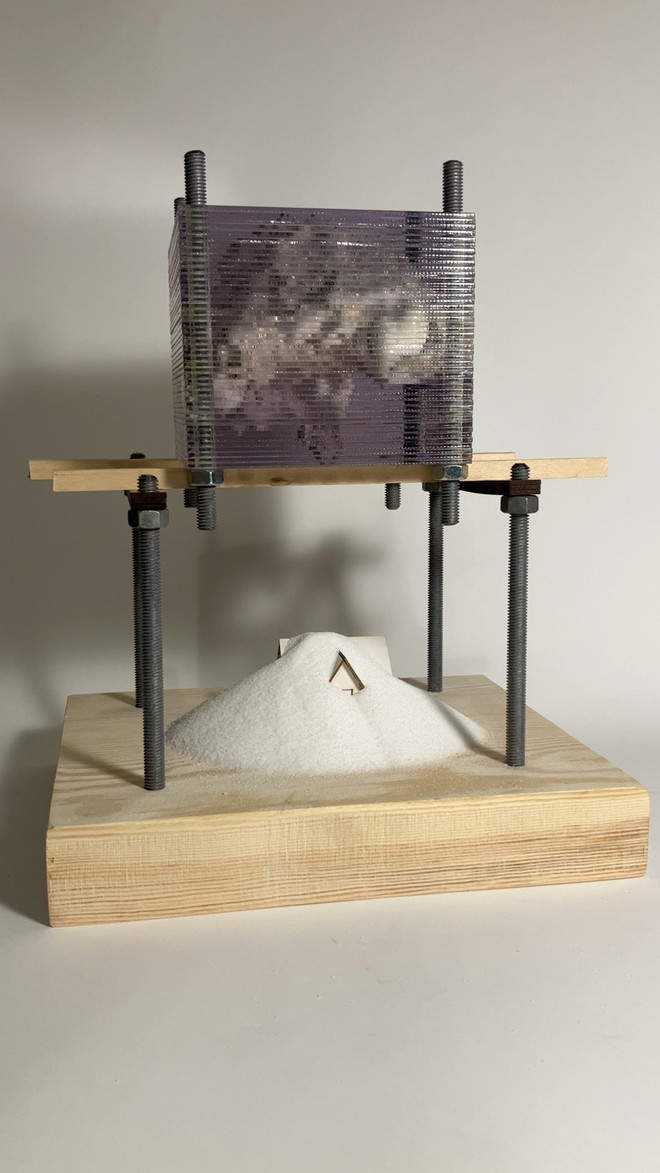

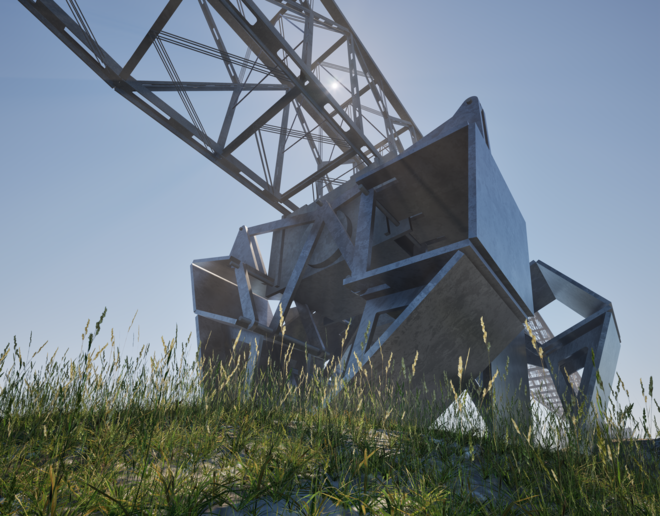

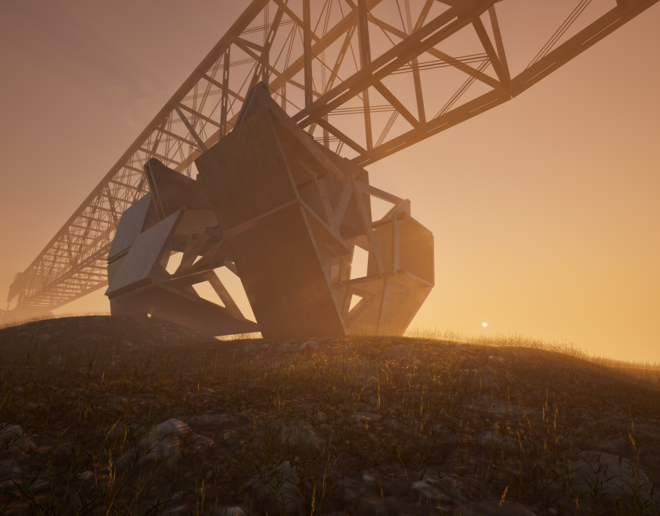

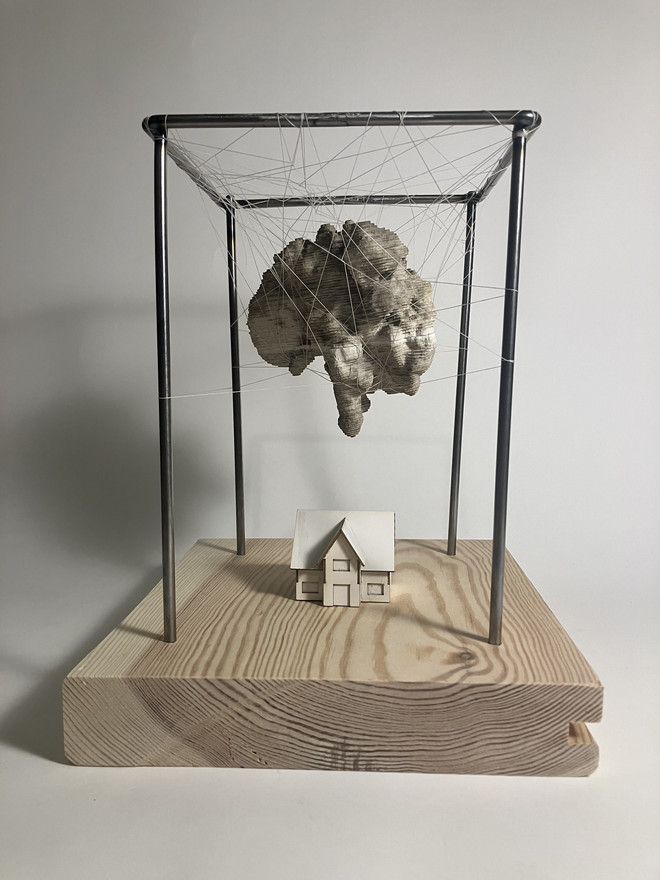

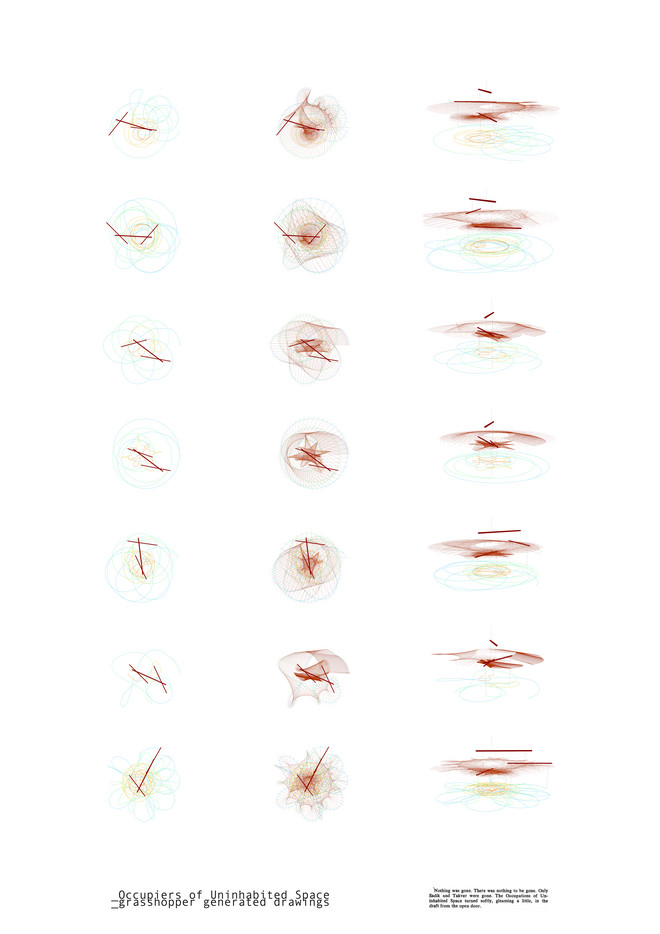

I used models as a form of exploration and analysis, allowing them to inform each other in repeatedly enmeshed iterations, a dance of knowing and acting. These models then influenced the development of the project, encircling the problem until the proposal became clear.

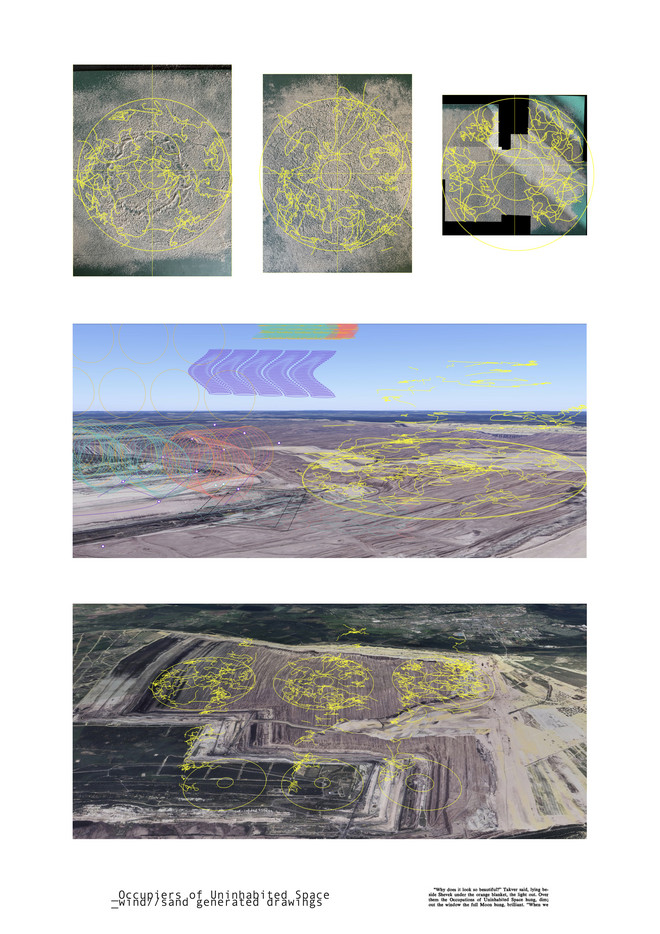

Here is a series of models I produced in the research stage of the project, after I conducted a number of interviews with locals in the region about the effects of air pollution, dust and noise from the mines. What does it mean to live both on and under these artificial landscapes? Does it permeate our understanding at all? The models attempt to look at air as an extension of the Anthropocene, how artificial and human shaped landscapes affect the air we breathe, and how this is a recursive loop, blurring bodies and environments. As Nerea Calvillo says: “We live with/in air” so we cannot ignore it. This is partly an attempt to make airs more visible, and partly to grasp at the moving, flowing complexities of the medium.

And what of the dust? It contains, it spreads, it settles, it permeates. It is ubiquitous. It talks. How do we listen?

Mining occupies a catabolic membrane between solid and gas, between slow and fast, between potential and action.

It is here in this thin layer of transition and translation that large-scale processes sublimate sedimentation into energy and back again. This mirrors the molecular breakdown of chemical compounds into smaller units and energy but enacted on a huge scale…as above so below.

Det Kongelige Akademi understøtter FN’s verdensmål

Siden 2017 har Det Kongelige Akademi arbejdet med FN’s verdensmål. Det afspejler sig i forskning, undervisning og afgangsprojekter. Dette projekt har forholdt sig til følgende FN-mål