A professional balance between sense and sensibility

This is the translation of the graduation speech given by Lene Dammand Lund on the 28th of June 2019.

Dear Graduates

Welcome to your graduation ceremony. My speech will be in Danish, but you can find a translation of the speech in English on some of the seats. Please pass them around.

It’s lovely to see you all, as well as your friends and family, here today. I would also like to welcome KADK’s instructors and other representatives – all deeply invested in these graduates.

I don’t know about you, but I’m a little nervous, excited and moved by this event – and perhaps you are too?

Obviously, today’s ceremony is about much more than presenting you with an envelope containing your certificates.

Those of us who are not graduating today are proud of and impressed by your accomplishments. I’m sure you are too. You should be, at any rate. Perhaps you’re excited, too, about what life has in store for you now? Not all of you have landed your first job, and perhaps other big decisions are waiting to be made as well?

Nerves, pride, and uncertainty – many emotions are at play. And here we are, bringing all these emotions together in a rite of passage as a shared experience, right here, right now.

Professional - and emotional

Now that we are feeling them, our emotions, let’s talk about them: emotions will play a vital role in your future professional endeavours. Today, you will join a profession, which processes emotions and/or is reliant on taking emotions seriously.

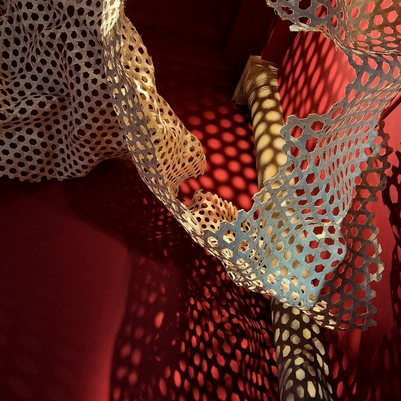

There is not a single project in the exhibition, which we will be going over to view in a moment that does not incorporate both an emotional and a rational basis – not even the conservators are exempt from this...

Let me give you three examples from this year's graduation projects.

Graphic designer Adam Lenzinger's project originates very directly from human emotions. He has developed an algorithm that can read the facial expression - whether you are happy, angry or sad - and transforms it into fonts that reflect the emotions that the face expresses. This allows you to create completely new opportunities for communication, which in an advanced way integrates our feelings.

Architect Mads Max Ibenfelt has based his project on a concrete problem in Sri Lanka. For a long time, the coast has been densely populated by large hotels and the population has therefore been cut off for access to the sea. Mads has designed a small hotel that allows the locals to walk from the main road and down to the beach via the hotel area - thus accessing their local nature area. His project originates from empathy, and a willingness to improve the joy of life and meaning of the locals.

Conservator Astrid Grinder Hansen has uncovered how to use colours in the Danish court theatre at Christiansborg from 1767. The colours testify to the role of the theatre in a socio-political context, and the colours can thus help us understand a bit more of our common historical heritage. Moreover, it is about the extent of emotions, understanding of which culture we are rounded off, and how previous generations lived and what symbols they used.

Culture and collective

You’ve completed your study programme at an artistic, cultural research institution, and all of you have invested emotions in the process of developing your study projects – so many emotions, in fact, that you have occasionally been utterly exhausted, not to say exasperated. I am not one of those who think that artists – or those of you who are now architects and designers – are endowed with an unusually abundant emotional life. However, I do know that you excel at processing the emotions you do feel with professionalism – which will be obvious to the naked eye at the exhibition.

You are not trained only to express your own feelings. You will get an opportunity to do jobs that are designed to meet functional needs: clothes for the body, roofs over heads, chairs to sit on, restorations of decomposing paintings, etc. Through them, you will be tasked with ensuring that we, too, continuously develop our collective emotions: that we uphold our shared physical culture, which stimulates interaction with whatever we individually might feel. In this sense, culture is defined as both the uniquely collective manner in which we do things and as a shared understanding and identity imparted to us through our physical surroundings.

In fact, this is actually the unique, crucial element that differentiates us as human beings from other species: our ability to experience suffering and pleasure by recalling something that has happened and by anticipating something that will happen – and by sharing these recollections and expectations with one another.

As humans, we imagine the past and the future – visually and linguistically. Our shared imagery becomes a cultural lodestar, articulated through our senses: taste, smell, hearing, touch and visual stimuli as well as through our inveterate, complex emotions involving desire, pleasure, depression, and so on.

To connect body and mind

Antonio Damasio is a Professor of Psychology, Philosophy and Neurology, no less, at the University of Southern California, and he is definitely a man to learn from, if you want to know more about emotions. According to Damasio, culture is simply a matter of orchestrating our emotions, and it is not driven by genes or finances.

Over the course of human history, philosophers have discussed the relationship between emotions and rational thought. According to Damasio, emotions play a critical role in making good decisions, which we obviously could not do without employing our rational skill-sets too. In other words, he dissociates himself from Descartes’ mind/body dualism pitting feelings and emotions against thought and reason. On the contrary, Damasio links the body to the mind. The soul breathes through the body, and joy and suffering are bodily responses, whether they arise in the skin, internal organs, bones or imagination. Emotions and rational thought have a symbiotic relationship.

If Damasio’s thorough, biologically based line of reasoning – that our emotions lead us to make good decisions, a process in which our rational skill-sets are indispensable – were to be generally well-known, then the world as we know it would probably look somewhat different.

Homo Economicus

Perhaps some of you were present when we celebrated the beginning of the new academic year in September last year. The event featured Frederik Stjernfelt and David Budtz Pedersen, joint authors of the book “Kampen om mennesket” (the struggle over the human identity). In their book, they describe eight different human types, ways of viewing ourselves as human beings: homo economicus, homo nationalis, homo sapiens, etc. They wrote the book because they felt our view of human nature had become too restricted. There are and should be many views of humanity.

In fact, one specific view of human nature is paramount: homo economicus. The fundamental aspect of homo economicus is that we do not have unlimited resources, so there is no room for emotions or so-called irrational behaviour, as this will inhibit us. According to this view of humanity, we are calculating beings whose every choice is aimed at one purpose: to best serve our own interests. Economics and the free market are seen as expedient regulators, and prices express an objective utility value because the market is regulated by our rational decisions.

In this view of humanity, emotions are disruptive and should preferably be avoided, because they undermine our ability to make sound, rational choices. Being at the mercy of one’s emotions is the worst thing that can happen to you. In addition, the distraction and chaos of populism, Trumpism and social media’s emotional porn has only given more credibility to the notion that we must make all our decisions based on clear-cut facts and statistics. One advocate of homo economicus argues for keeping emotions out of the climate debate and trusting that science and innovative technology will solve all our problems. He is closely aligned with the homo economicus view of not dwelling on the past or our cultural and natural heritage, and being devoid of nostalgia about this. One should only look forward and focus on maximising quantifiable future gains.

You have also encountered the homo economicus viewpoint on your way through the educational system. It is the explicit goal of certain politicians that you must contribute to economic growth and thus to social prosperity. It is argued that the best way to do this is by finding the study programme and career that will maximise your life-long income – and then by achieving this goal as quickly as possible.

No social cohesion without culture

I don’t know what Damasio would have to say about homo economicus, but I believe that he would have two opinions of this view of humanity in its pure form (which is fortunately only a theory). One is that if we never look back, we disregard the unique human advantage which has enabled us to use artefacts and environments of the past to create a common ideal of the future that is richer than if we only had to consider the present and future. Secondly, he would probably argue that if one truly acted out this view of the world, where human decisions are made only according to a rational maximisation of individual needs, then, as human beings, we would squander our most important survival card: we would have no common culture and thus no social cohesion, and society would presumably collapse.

The balance between emotions and rational thinking

Stjernfelt and Budtz Pedersen’s book on different views of humanity includes homo emotionalis. As the name suggests, this view of humanity deems human emotion the most crucial aspect of our relationship with the world.

Here, too, Damasio would probably warn us to strike a balance between body and mind, emotions and rational thinking.

As mentioned, arriving at this equilibrium is actually not that easy. In a world of seductive demagogues and ubiquitous media who want us to disregard reason in favour of spontaneous emotions, it can be rather alarming to consider where these emotions could lead.

That’s where you enter the picture, though. We need more people like you who take a professional approach to their work by drawing on emotions, common sense and facts. People who do not see this as both/and, not either/or.

We need you to strike this balance between reason and emotion, which seems to repeatedly get out of kilter.

You must find your inner homo economicus when you need to be paid for your work. Moreover, never work for nothing, for heaven’s sake, because, if you do, you will be unable to afford the pursuit of the quality you are trained to be capable of creating. Also, remember to stay up to date at all times with research and other knowledge in your field of specialisation.

Nevertheless, you must also insist on never abandoning your homo emotionalis, even if it cannot be monetarised and you occasionally feel that you are the only one talking about this unquantifiable entity.

You must go out and be instrumental in upholding and enriching our common culture through language, imagery and tangible sensory experiences. You must also actively participate in finding specific solutions to the challenges expressed in the Sustainable Development Goals, for instance. Solutions that consider the needs of human beings and our natural environment at the same time. Solutions that go beyond achieving only one sustainable development goal at the expense of the others.

You must help society – both in Denmark and in the world at large – to take a sophisticated approach to exploiting our human capacity both to look back and to evoke shared visions of a desirable future. You must come up with visions that address the challenges we face, and, not least, plot a course to improve the human condition beyond what we have today. Reduce the role of consumption in our lives – or at least render it sustainable. Because our lives will develop into something entirely different if we pursue the Sustainable Development Goals. The pressure on our resources caused by climate change and other factors will require us to pursue new ways of living, and there are no assurances that the solutions we find will be widely embraced or will align with the cultural values we have right now.

This explains our decision to incorporate the Sustainable Development Goals into our work at KADK. Because, in addition to specific solutions, we have a unique capacity to advance an understanding of the enormous emotional upheaval and cultural development required to achieve these goals – and encourage the perception that these solutions will not only be technological, financial or functional, but that we must include emotions as integral elements of the entire process.

Climate debate - with feelings

During the recent national elections, an oft-repeated phrase was “climate hysteria”. There were politicians who wanted to urge caution – we should take a rational approach to climate change.

Hystrionics are obviously pointless, but emotions such as anxiety and compassion for those hardest hit by climate change are important, even indispensable drivers of change. In our enthusiasm for science, we tend to forget that science is shrouded in – and does not make sense without – emotions, which cannot be substantiated by evidence. Medical science does not originate from science. It arises from a wish to reduce the feelings of pain and feelings of grief over the loss of others – so, without emotions, there would be no science. It simply makes no sense to see one without the other. Therefore, emotions must obviously be integral to the climate debate. However, we must take a balanced, professional approach to how we use them – which is precisely what you are trained to do. In many ways this is the essence of the education you have received here at KADK.

It will be eternally challenging – for you, as well – to strike the right balance and you will not be able to strike this balance, nor resolve the problems you will be confronted with, by yourself.

The trick is to find good colleagues and partners – preferably with a background that differs from yours.

Being able to take a multidisciplinary approach is becoming increasingly important. It’s a skill-set in its own right. One way for you to learn this quickly is by seeking jobs that may not seem self-evident – in other words the ones not everyone else is seeking.

Search everywhere, and be bold!

Try challenging yourselves in relation to what you imagine to be the job of your dreams. My guess is that there are many more jobs relevant to you waiting out there than you can think of offhand. Meet up with friends over coffee to shine a light on this and widen your scope of options. You have acquired a sound area of specialisation to stand you in good stead – now you must go out and learn to bring it into play.

I look forward to seeing what you go on to do, and I’m not saying farewell, but welcoming you back again soon to further your studies, in partnership or as colleagues.