Shifting States: A Climate Commons in Ilulissat

Could we rethink the way we build for a changing climate and use architecture to help convey the sensory impact of climate change on a more human scale to foster agency, awareness and action?

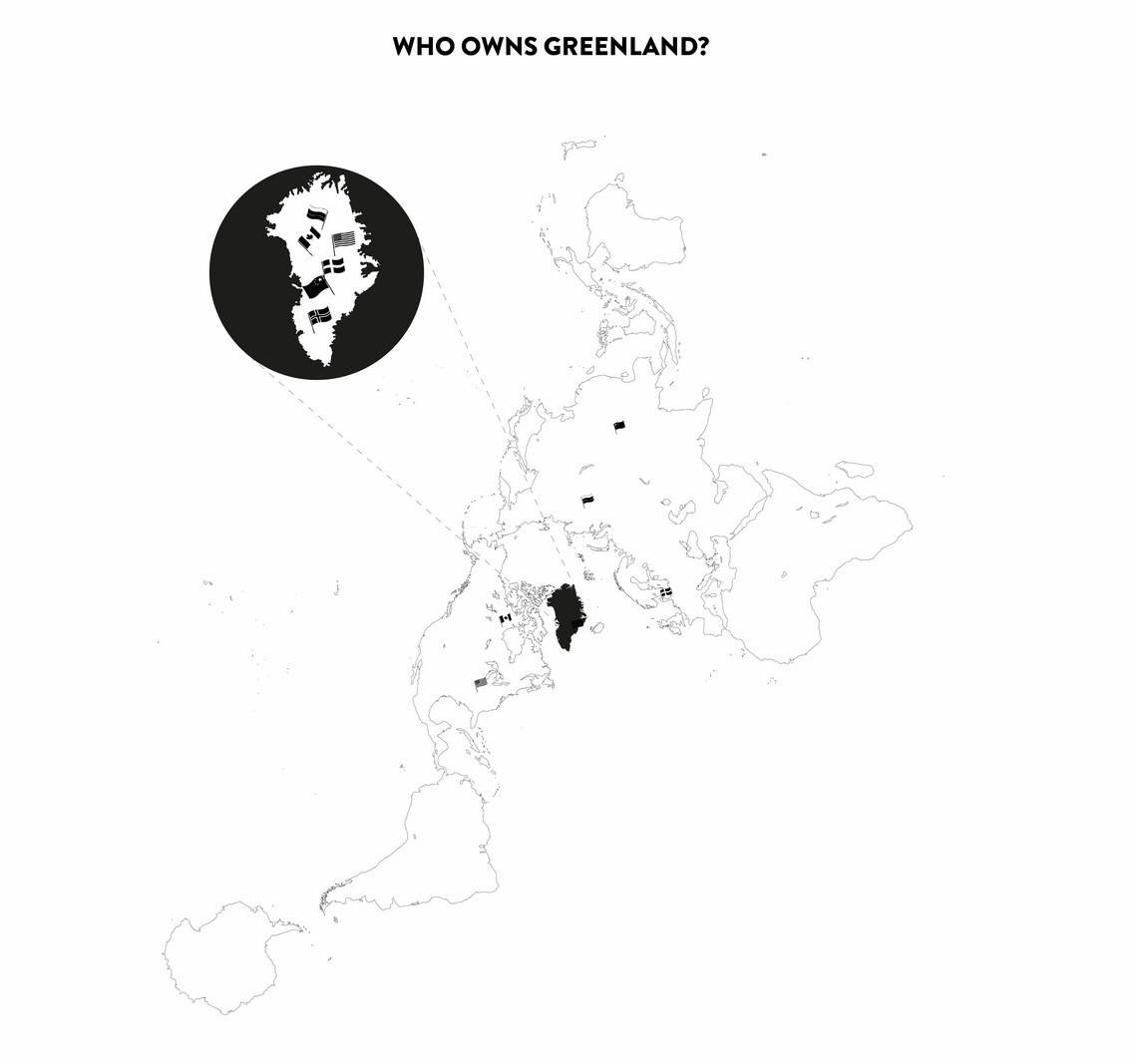

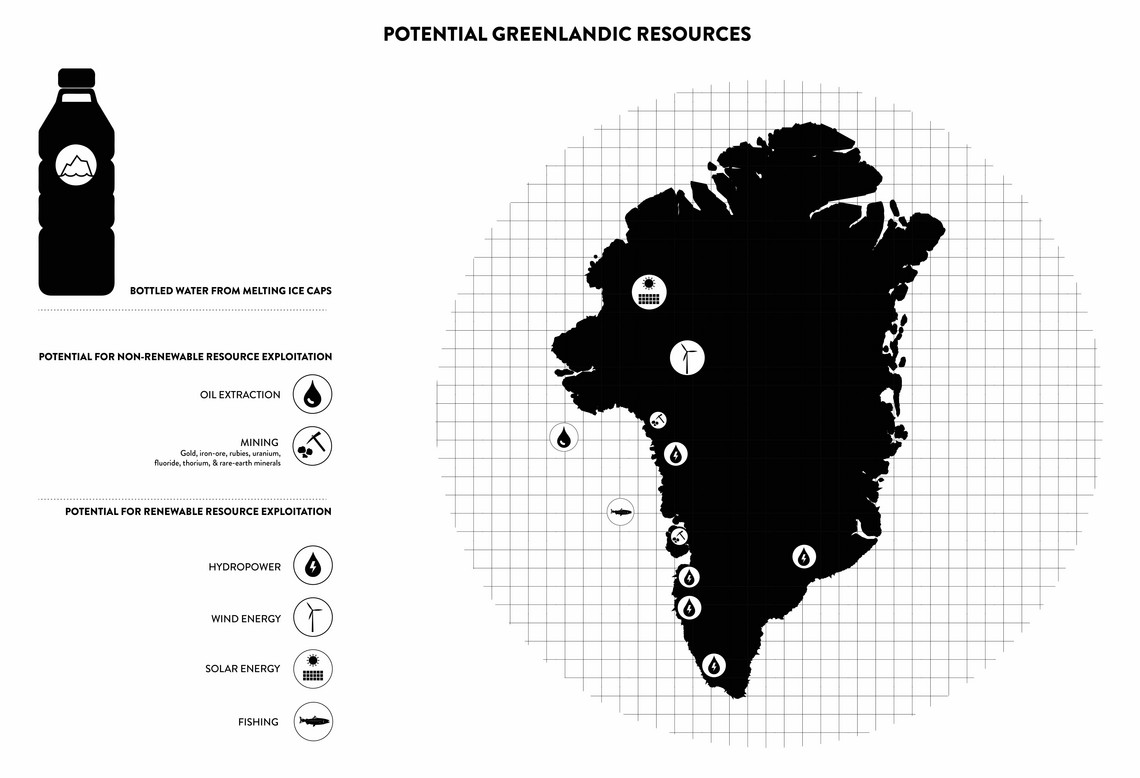

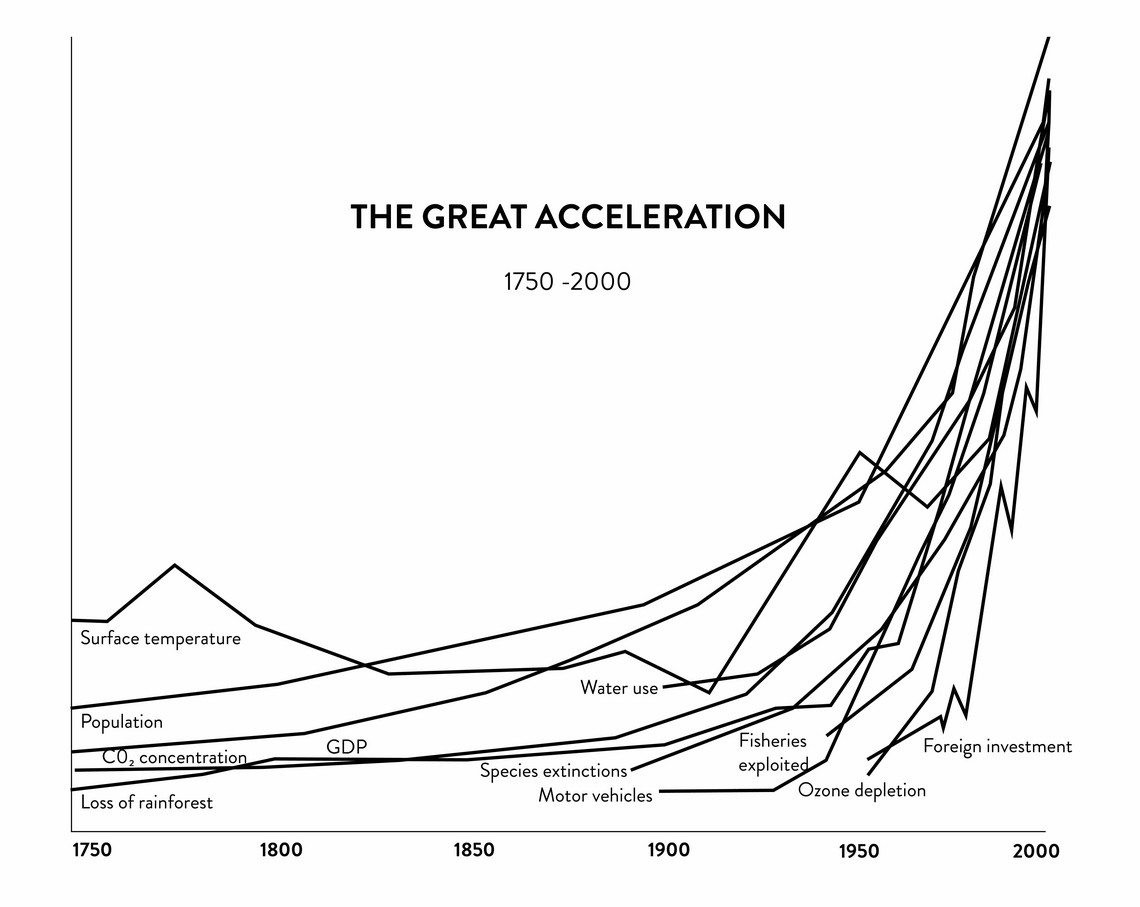

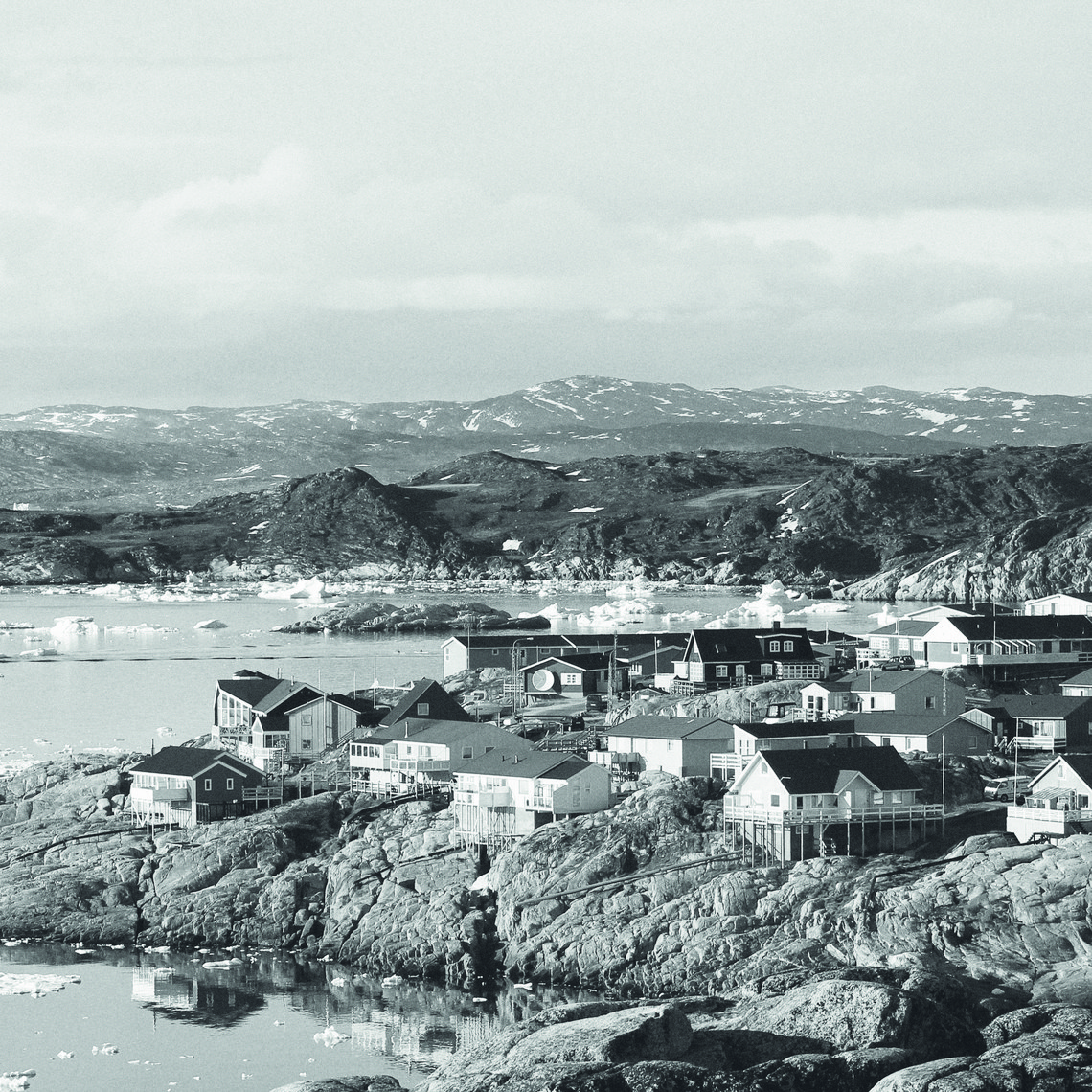

Greenland has found itself in the centre of a new world map emerging from the effects of climate change. With warming happening twice as fast as the global average and the rapid melting of its glaciers, Ilulissat, Greenland, is a visible manifestation of climate change. Despite the massive challenges, the melting sea ice has opened up access to natural resources, new shipping routes, and other economic opportunities which are drawing interest from other nations. Yet for most, our personal exposure to the impacts of climate change has until recently been largely experienced on a distanced, colossal scale – threats and images of the melting ice caps, apocalyptic storms and raging wildfires saturate the media. The overwhelming magnitude of these ‘hyperobjects’ is nearly beyond our comprehension, and thus leads to a collective inertia. The narrative needs to be reframed in order to avoid to shift climate fatigue to climate action.

Economy of Ecologies

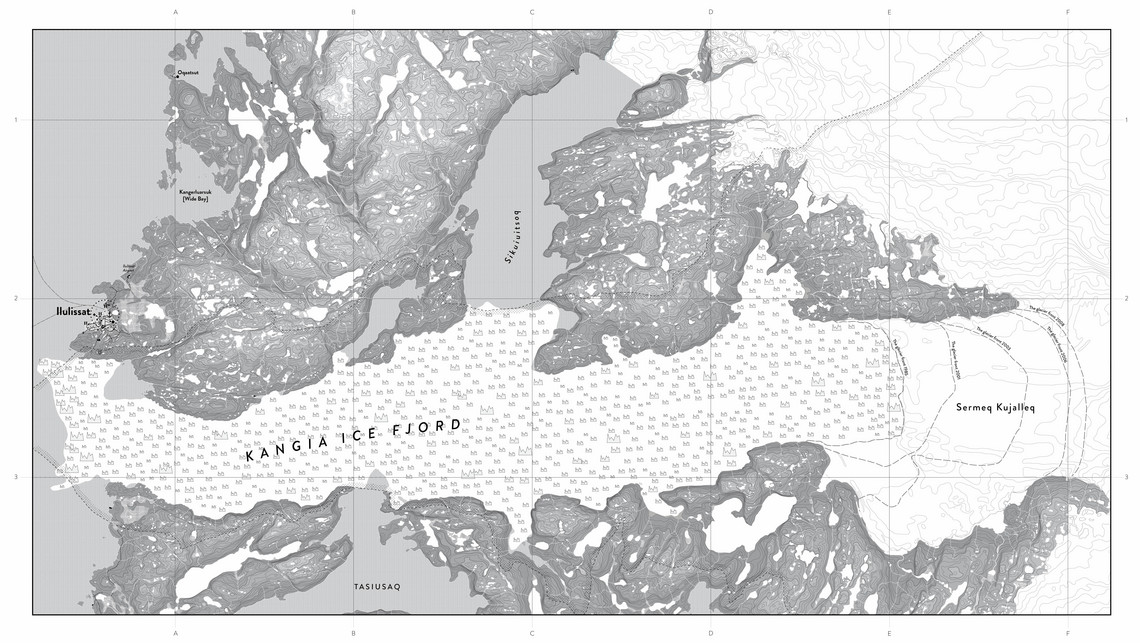

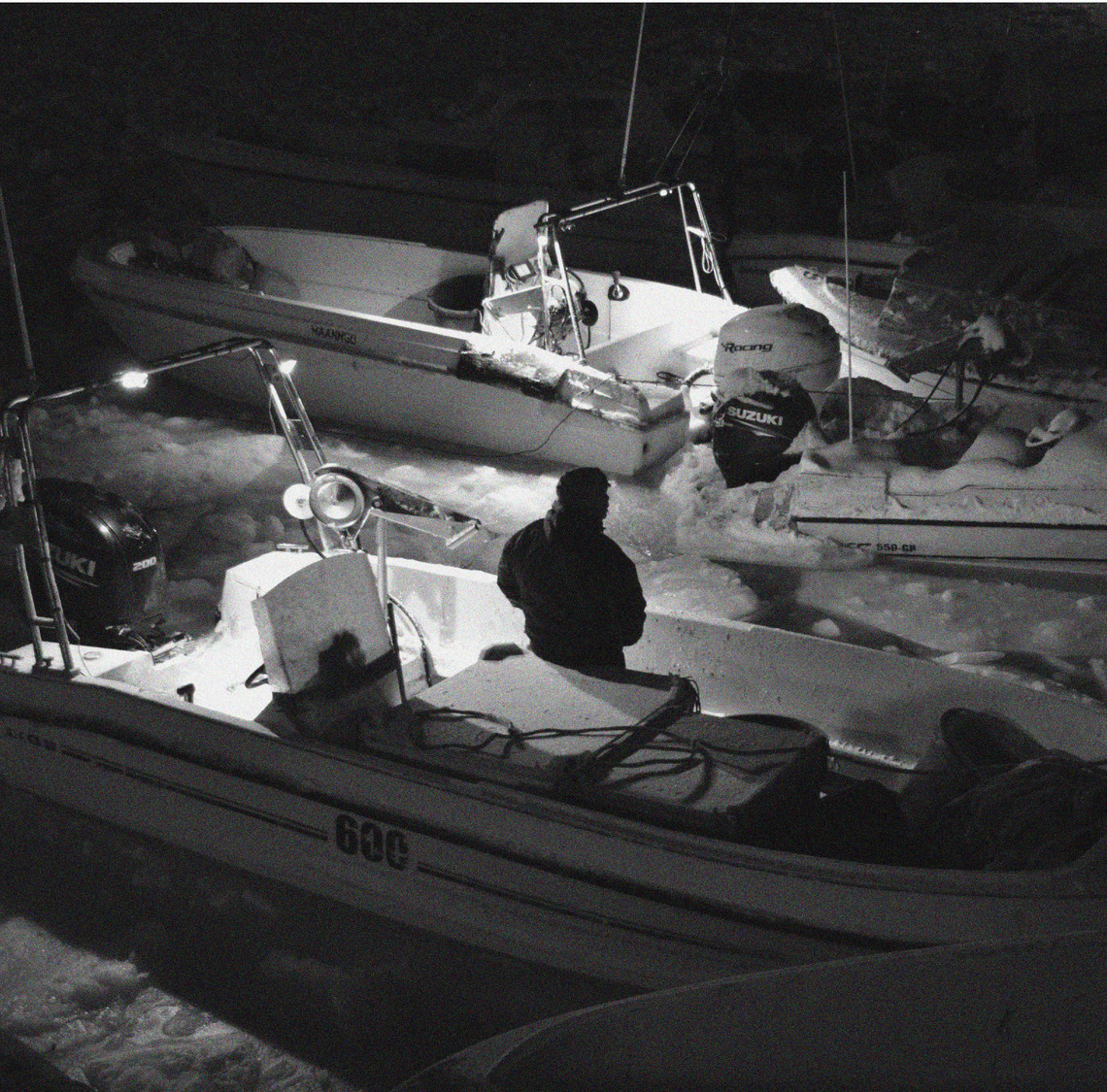

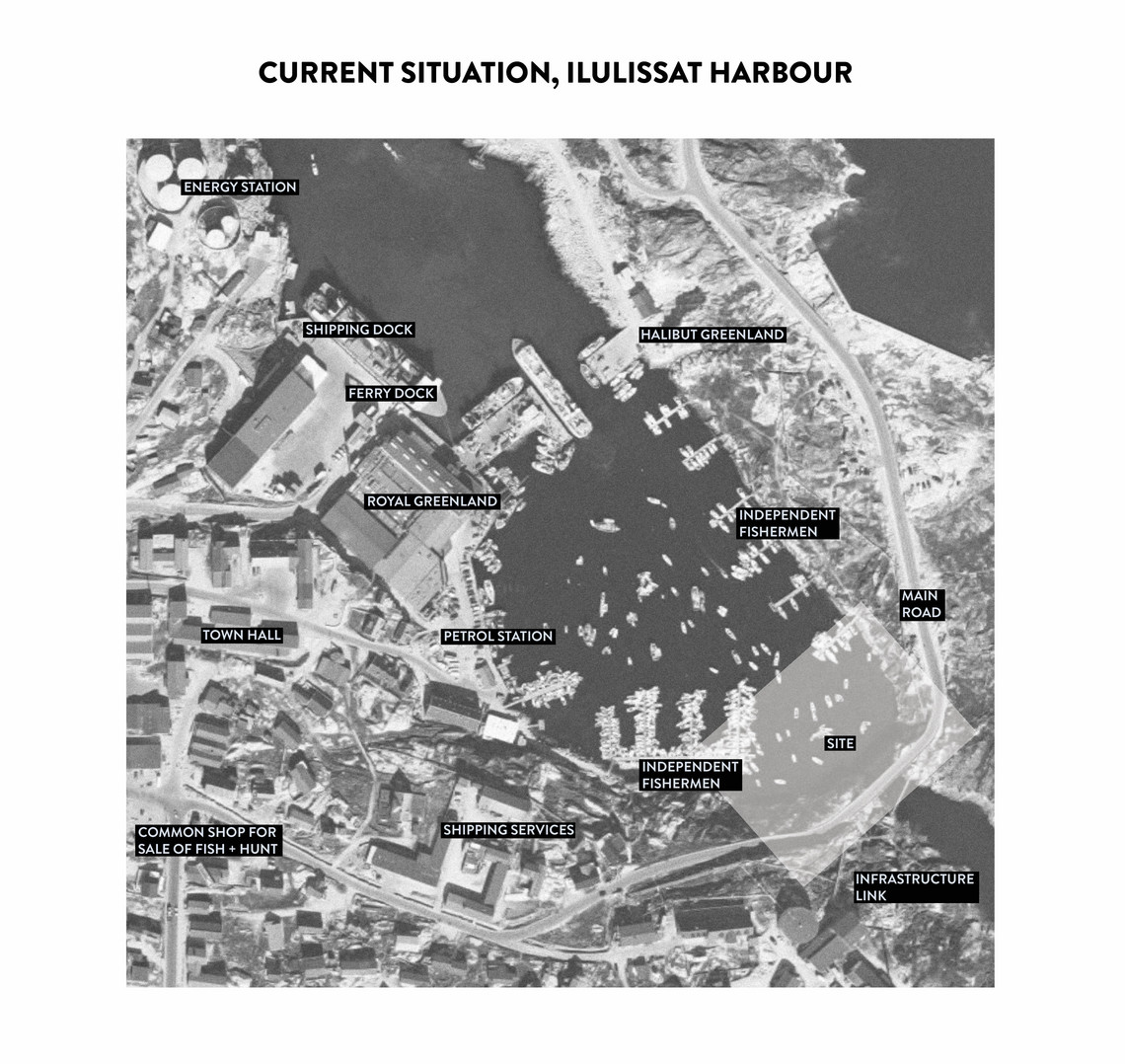

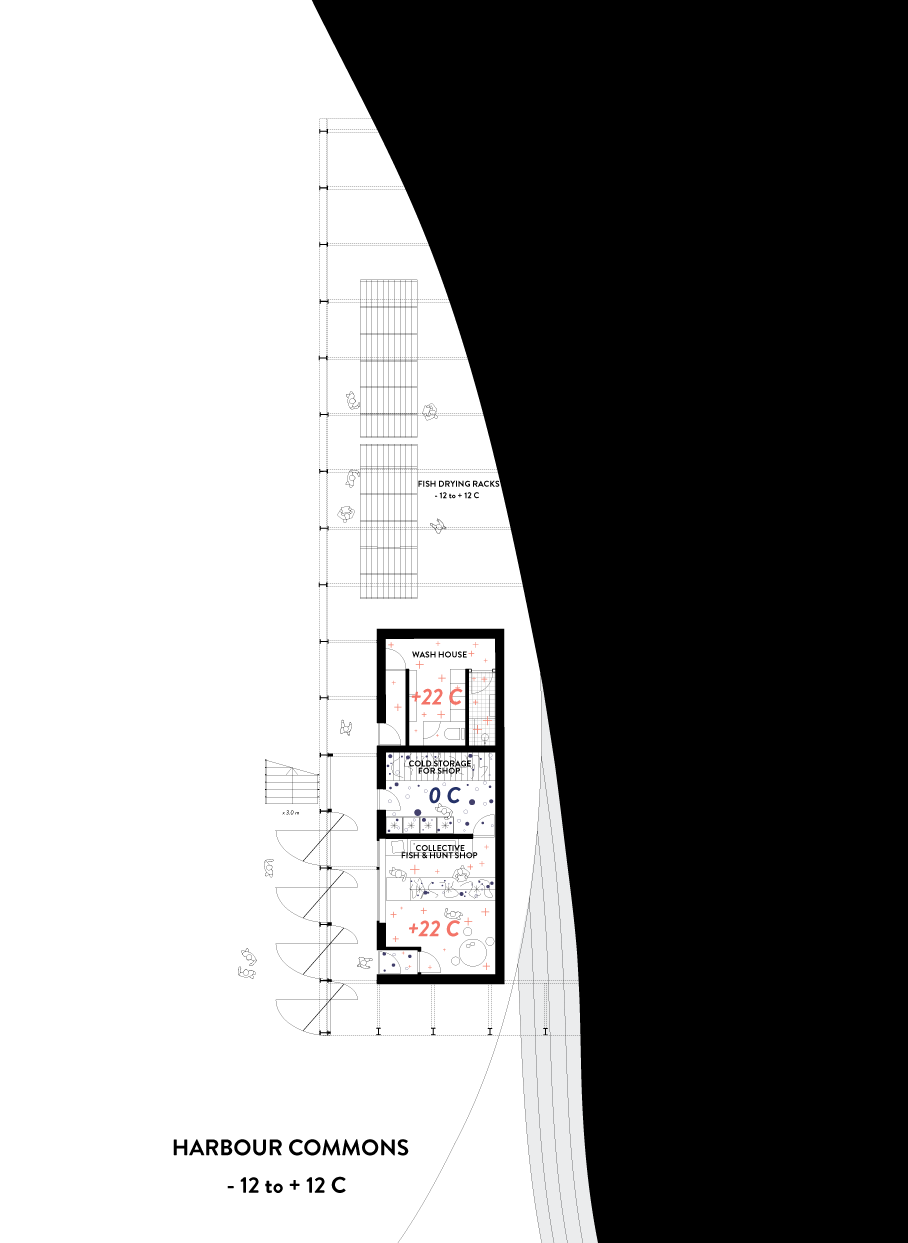

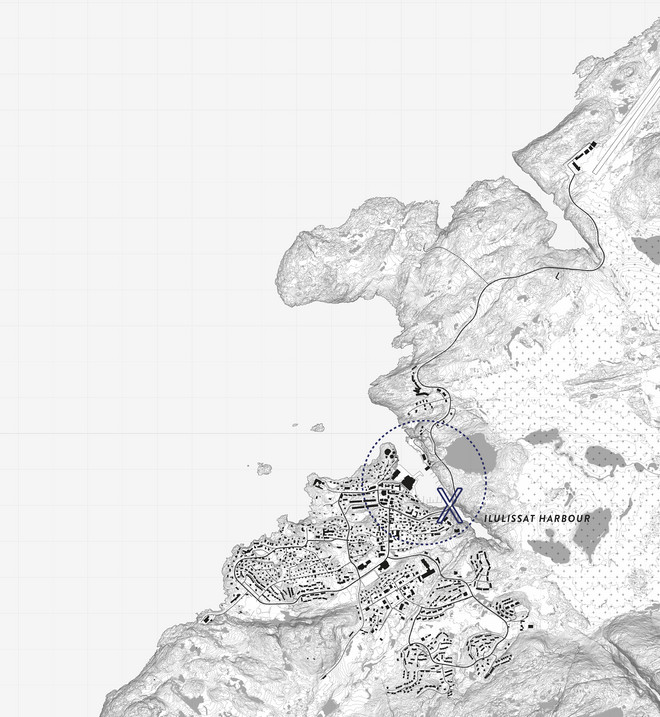

Due to Greenland’s increasingly strategically important position, the country is vulnerable to neo-colonialism, which could manifest in socio-economic dependency on foreign oil and mining companies and exploitation of the natural landscape. In Ilulissat, the main industries of tourism and fishing are projected to develop even more with a new international airport planned for 2023. Ilulissat’s current harbour is too small to accommodate the town’s current needs and the coming changes related to fishing, shipping and tourism. As the harbours are the hearts of the settlements and towns in Greenland and fishing is the lifeblood of the country’s economy, it will be critical to think of new alternatives which incorporate the future complexities the area is facing.

The Climate Commons

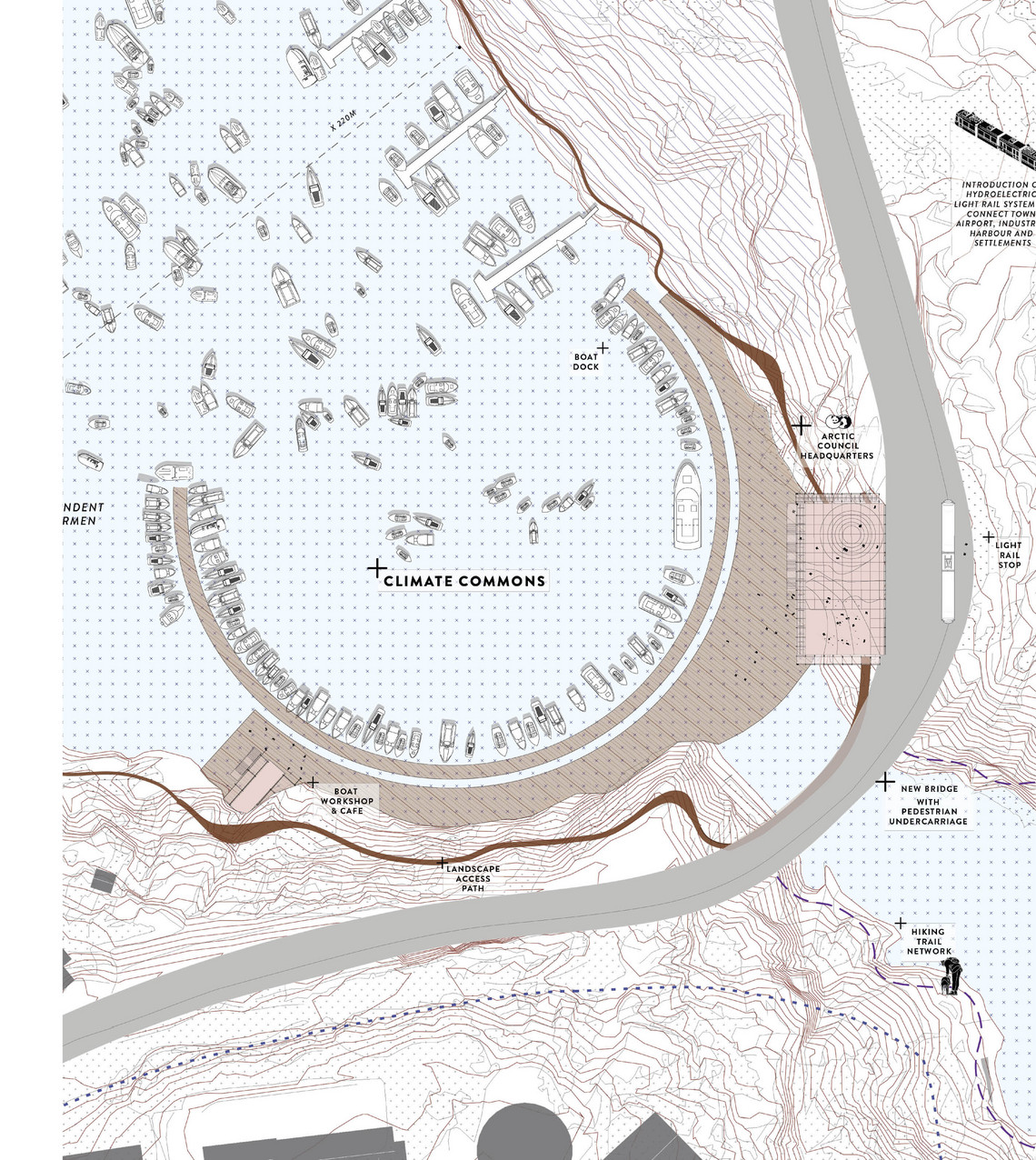

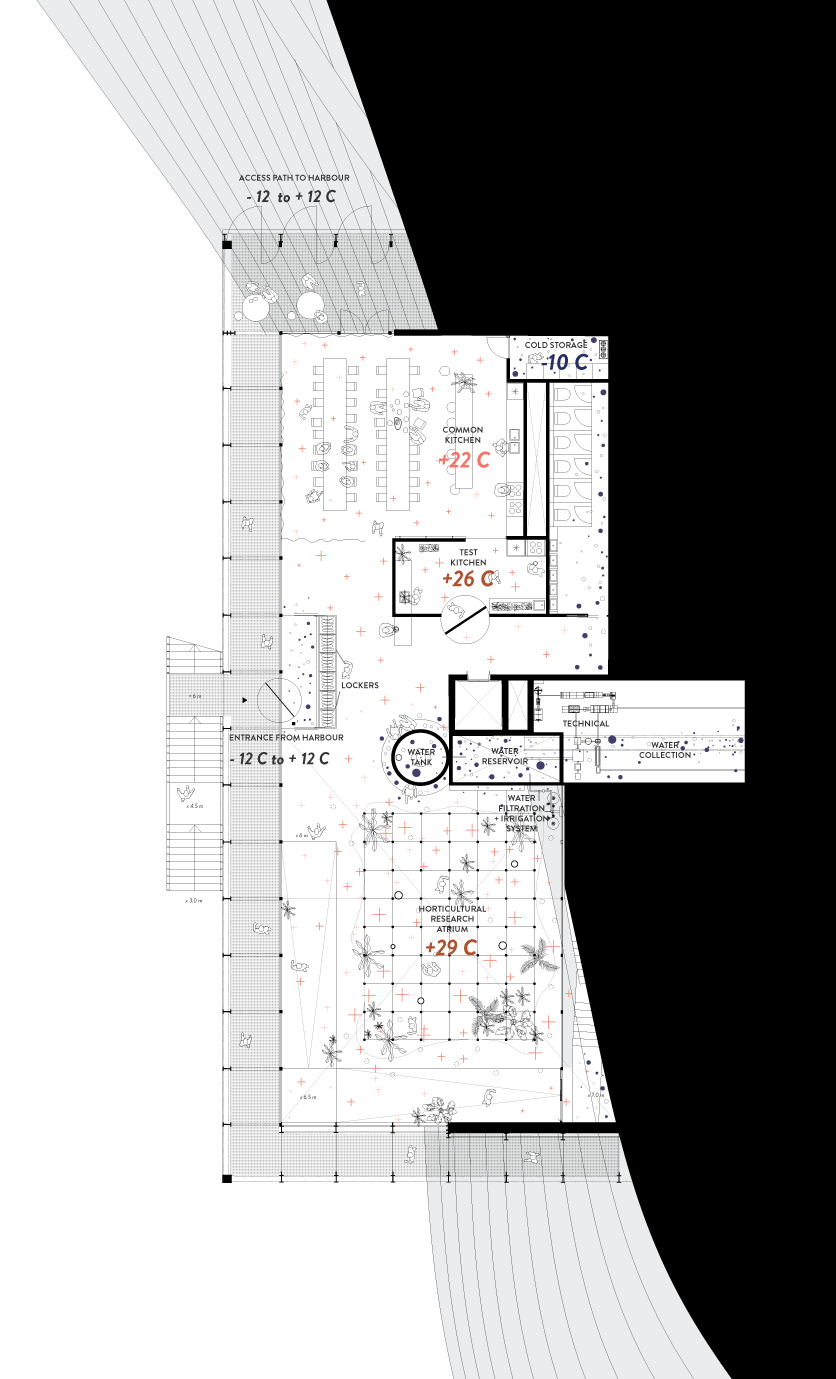

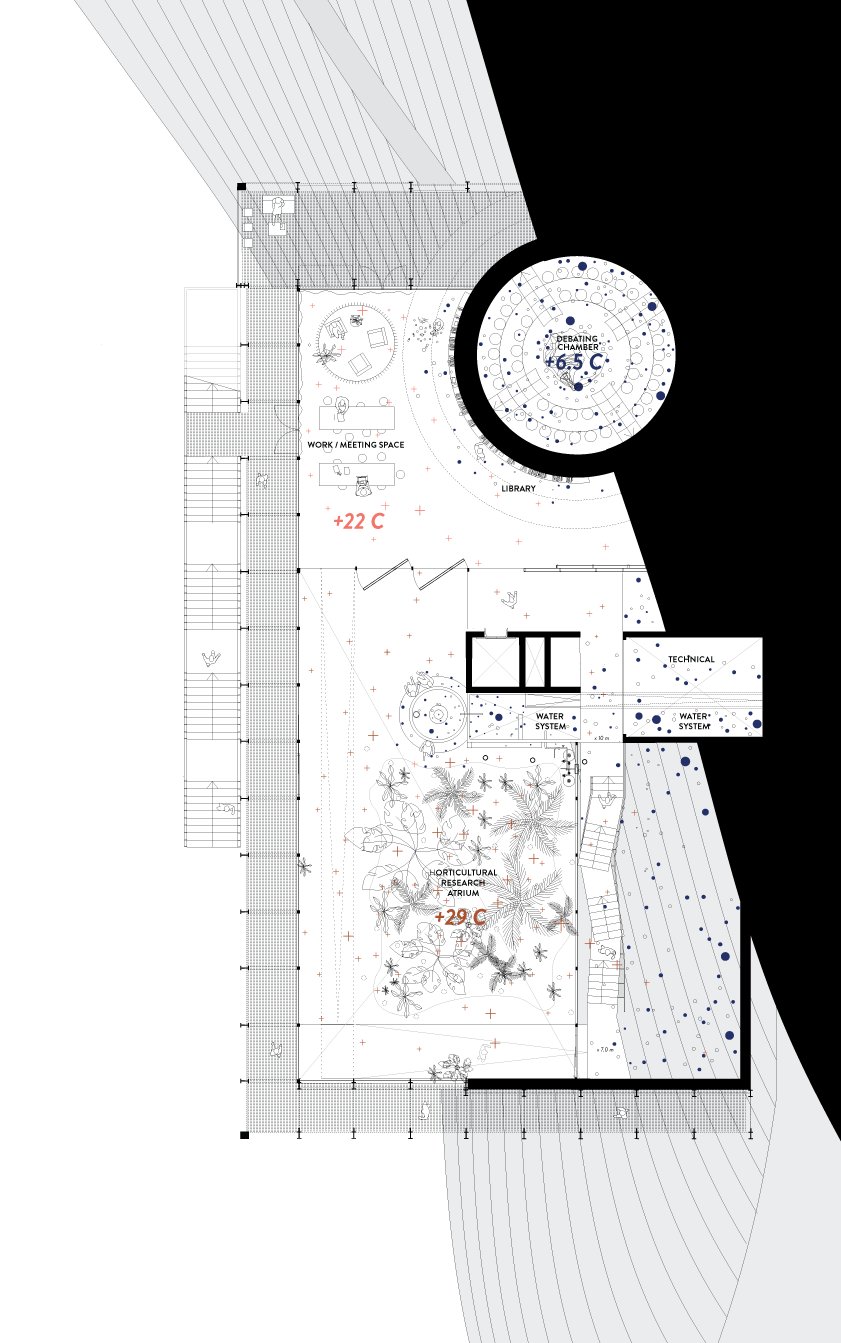

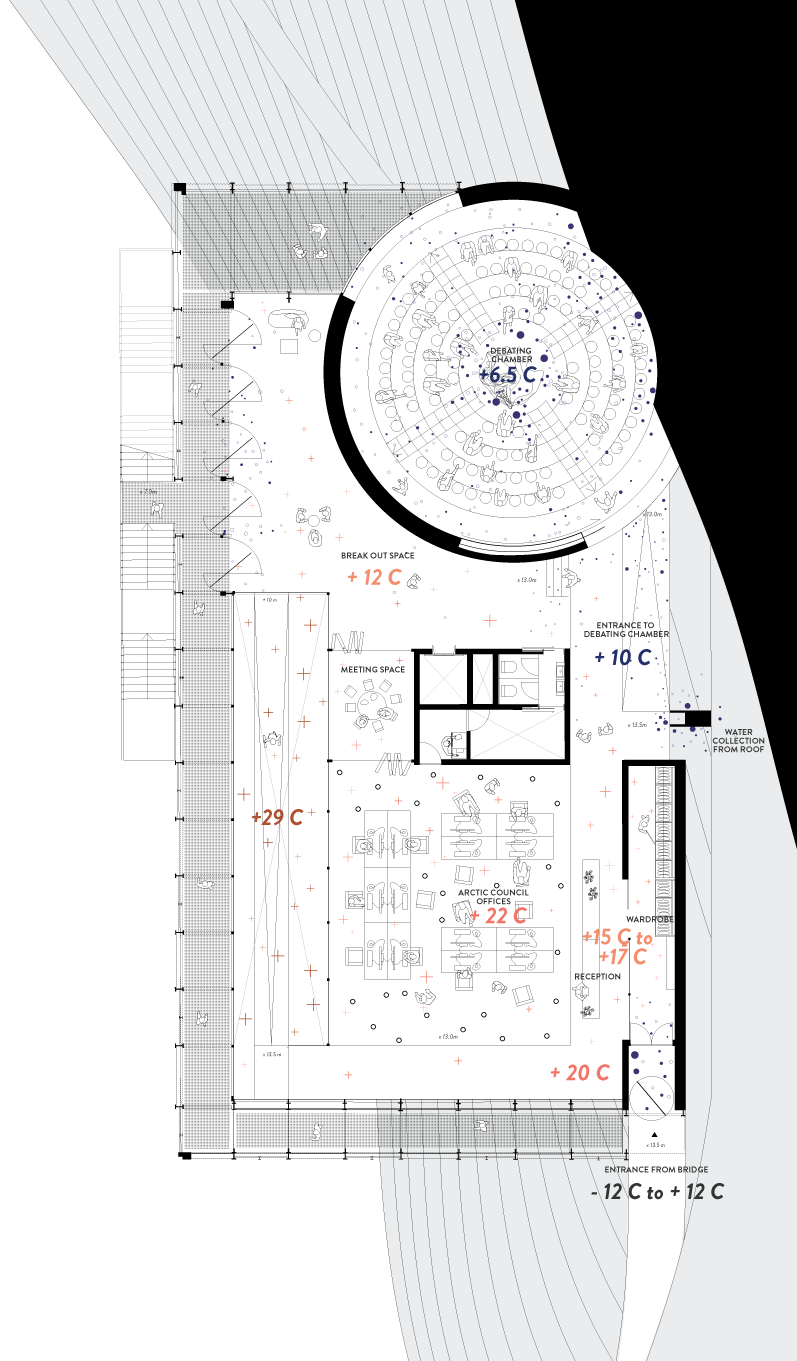

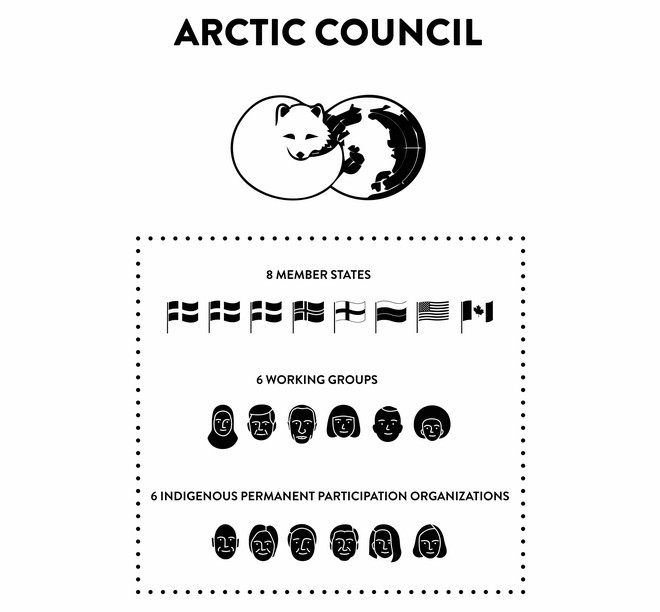

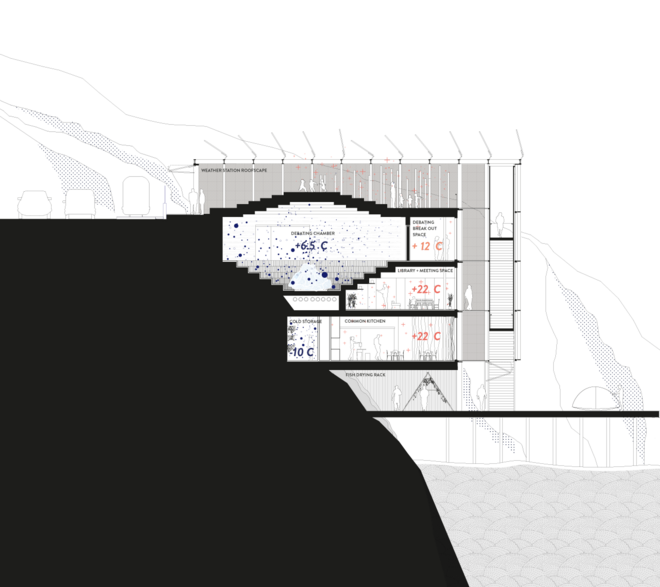

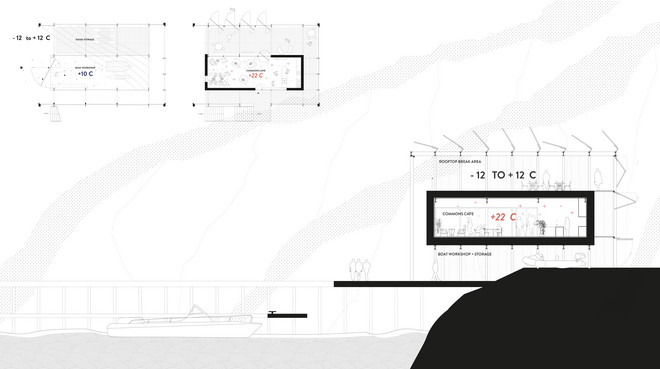

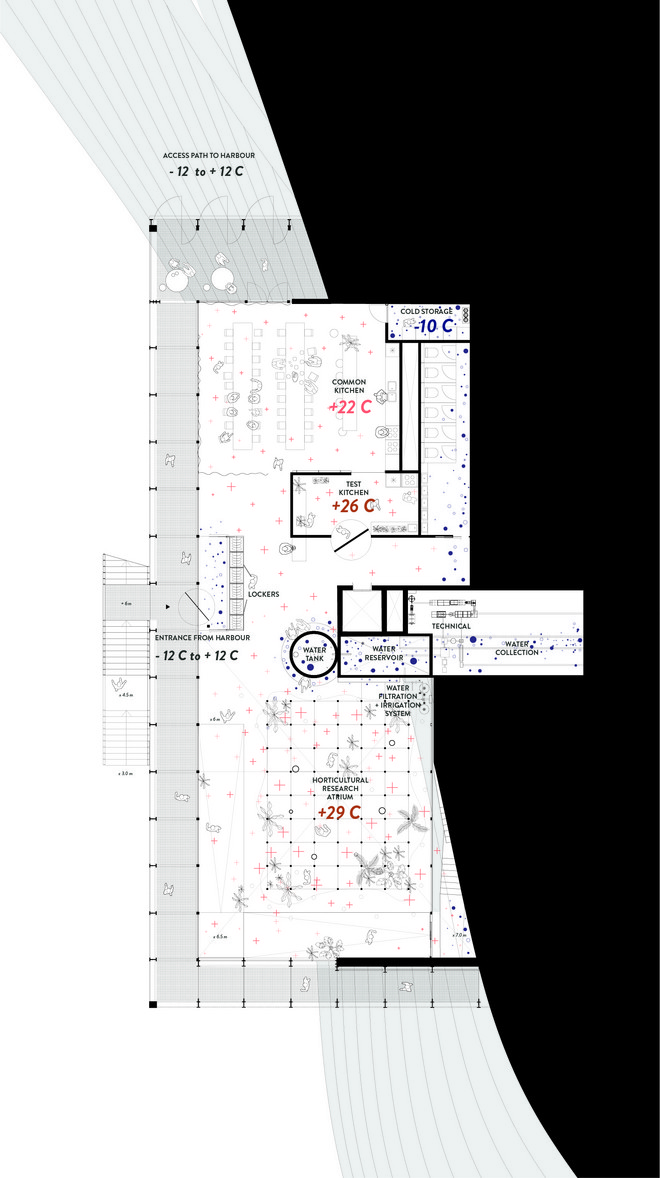

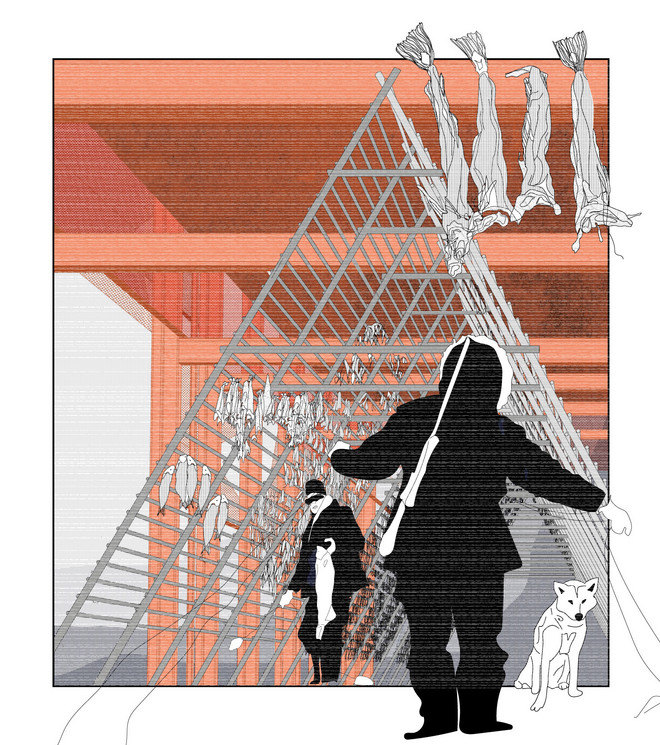

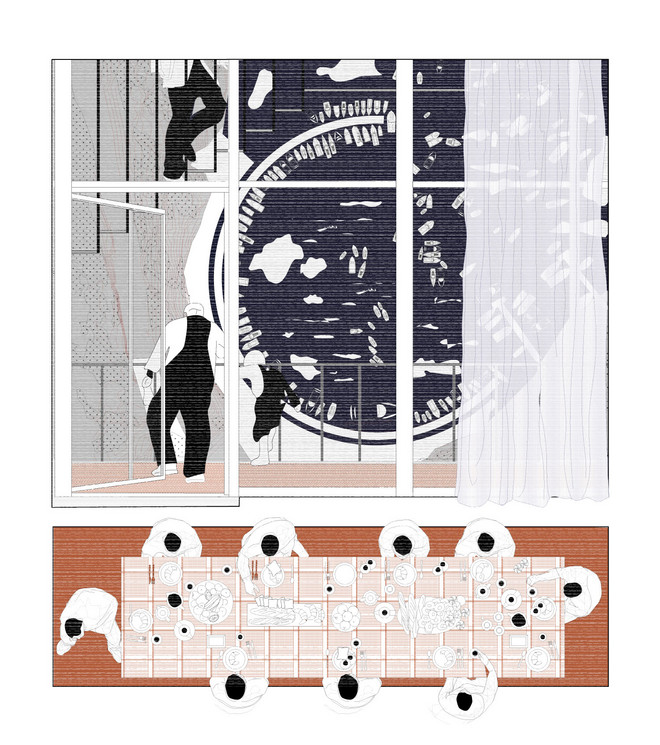

Architecture alone cannot stop climate change, but should be a part of the systemic shifts we need to take. The intervention seeks to explore the development of regional political frameworks and social infrastructure to support a resilient Arctic in an increasingly vulnerable position. The dual program consists of a headquarters for the Arctic Council and overlapping common spaces for the local fishermen and town community. As political institutions are typically closed off to the public, and only accessible to those wielding power, we wanted to explore how opening the headquarters and promoting transparency and interaction with a directly involved population would affect both policy making and individual political engagement.

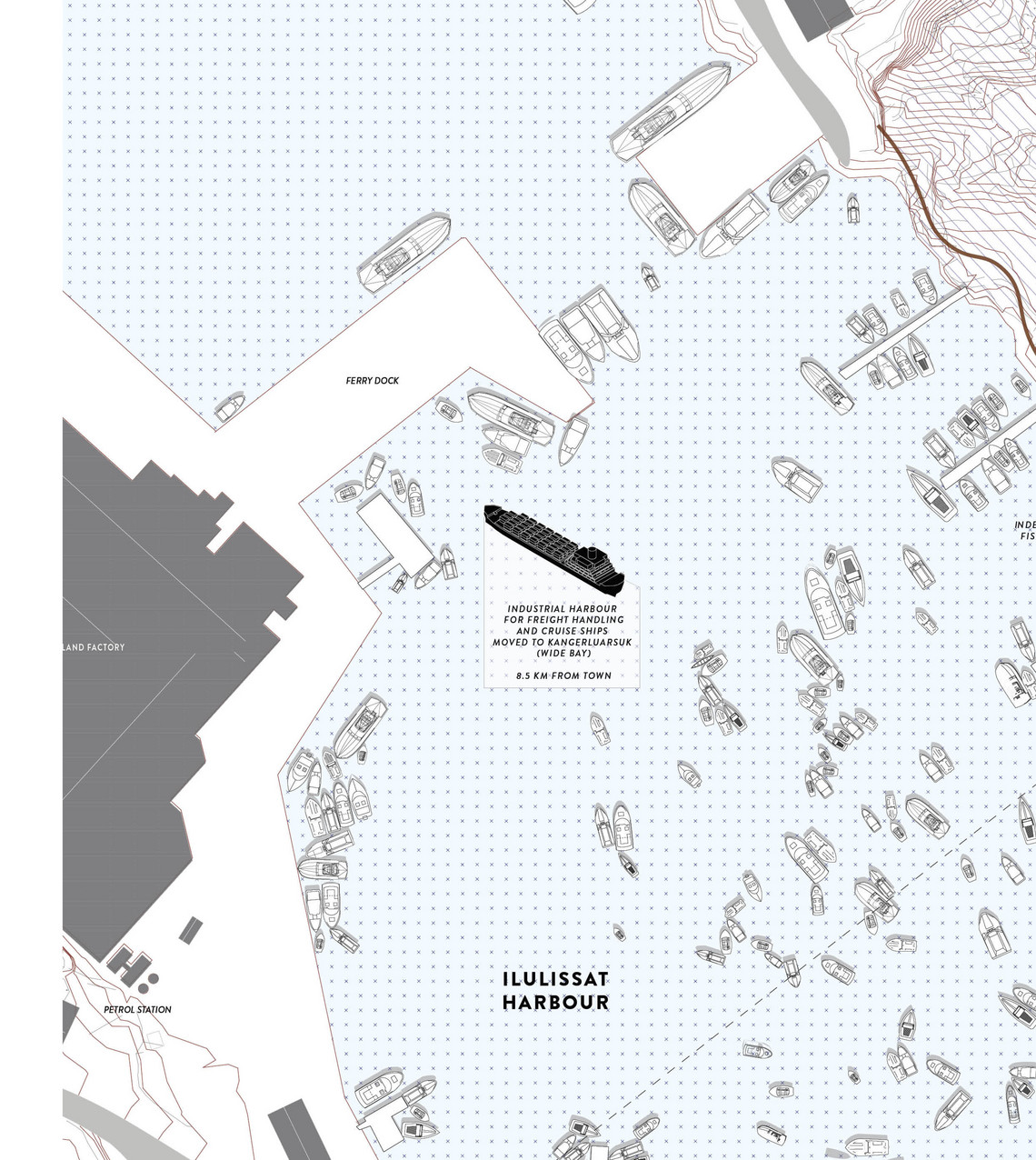

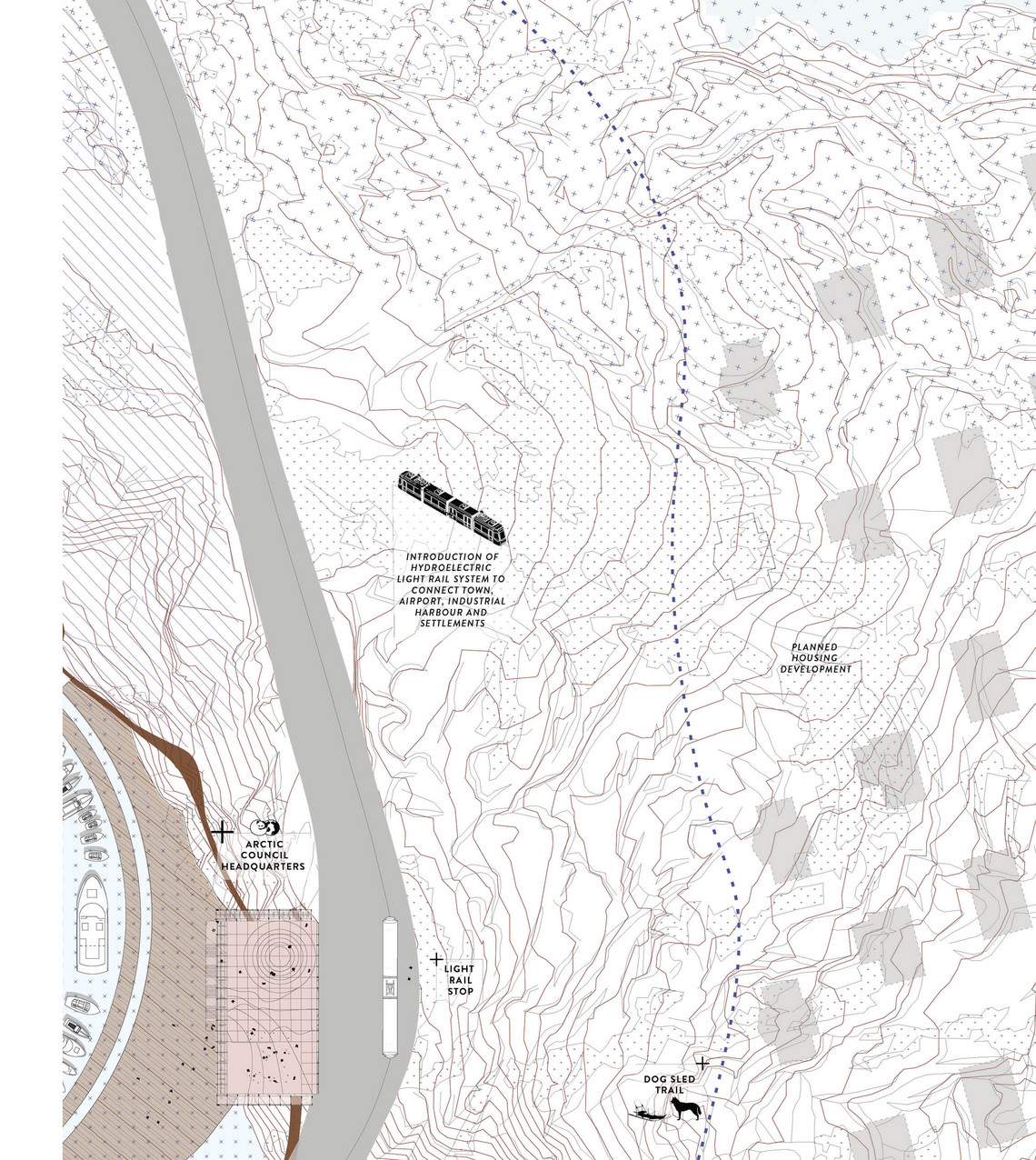

Strategic Plan for Ilulissat Harbour

A Fluid Infrastructure

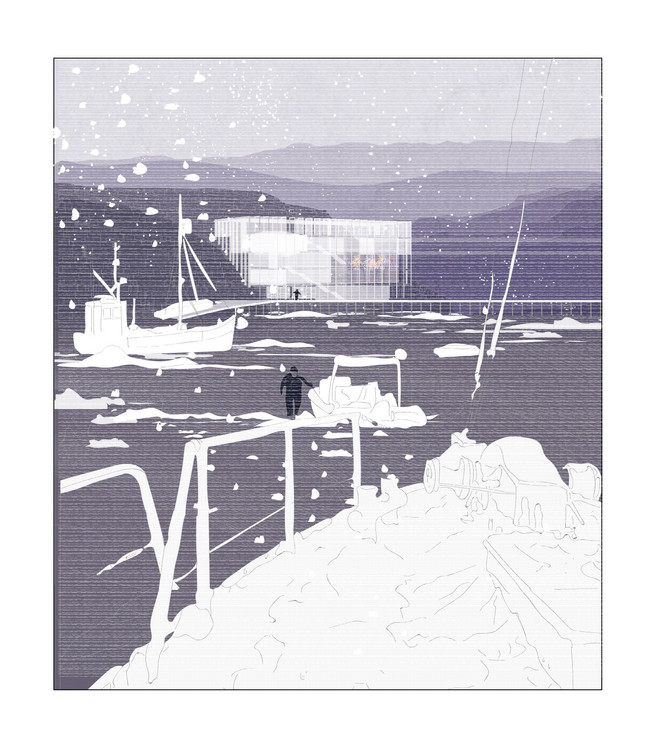

Infrastructure has historically and continues to be intrinscally linked to polity. With the town already investing in infrastructural updates and expansions, our intervention uses this is an opportunity. Building and infrastructure implementation, while critical in Greenland, is expensive and difficult, so coupling these together reduces costs and resources. In Greenland, water is the most essential form of infrastructure. For us in Denmark, it can be said that land connects and water separates but for Greenlanders it is the reverse. Boats are the primary mode of transport, and therefore a focus on strengthening harbour infrastructure was vital in our project. In wanting to make the harbour more accessible, we were led to the circular harbour structure as an intervention strategy. The open circle embraces the harbour and connects the landscape, giving a sense of assembly and providing a platform for the fishermen and the town. Amplifying the fluid mode of circulation of the town, we designed a network of paths to allow for multiple access points and flows - both to the harbour but also to the buildings, bridge, and surrounding landscape.

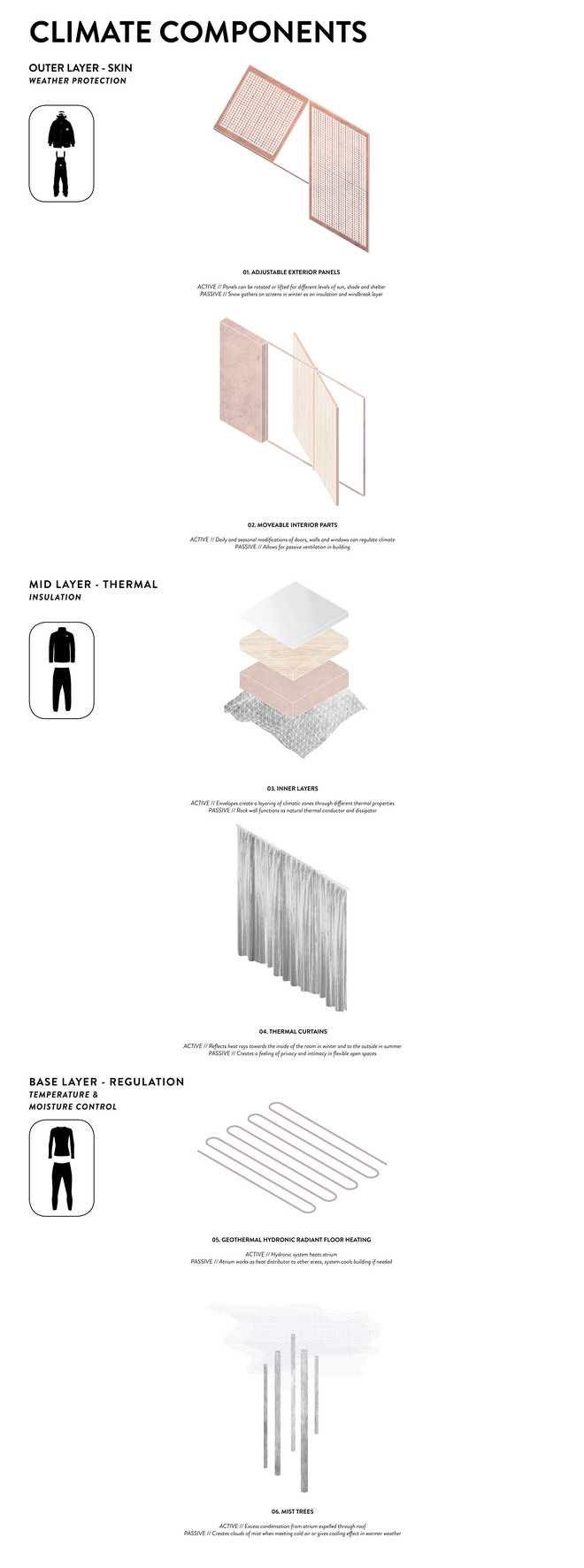

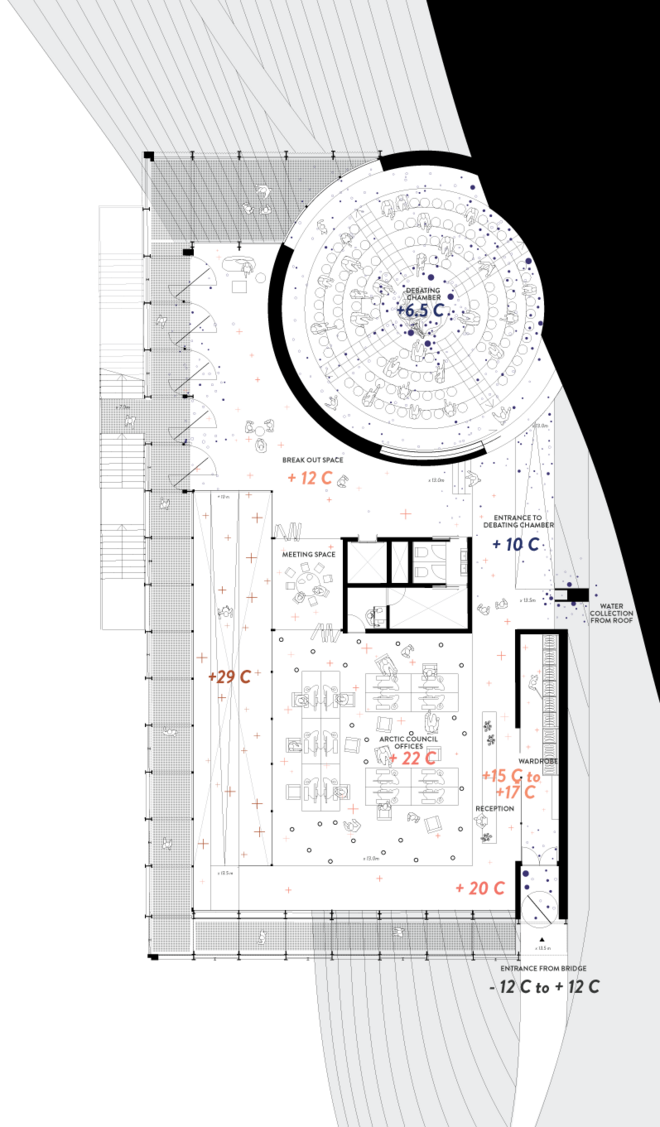

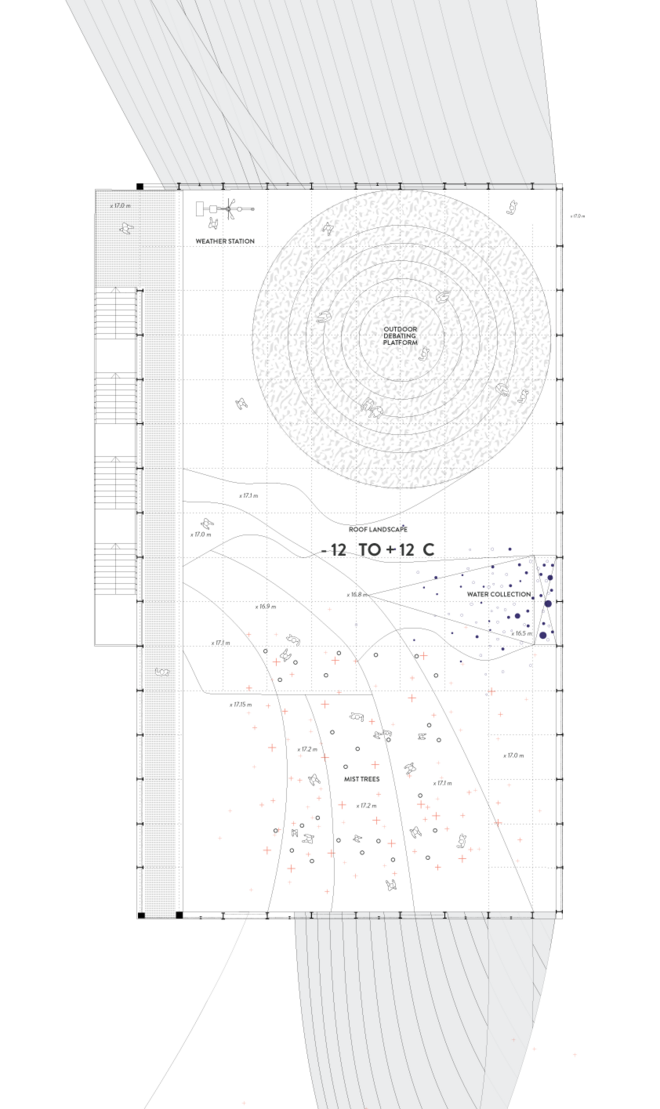

A Climatic Architecture

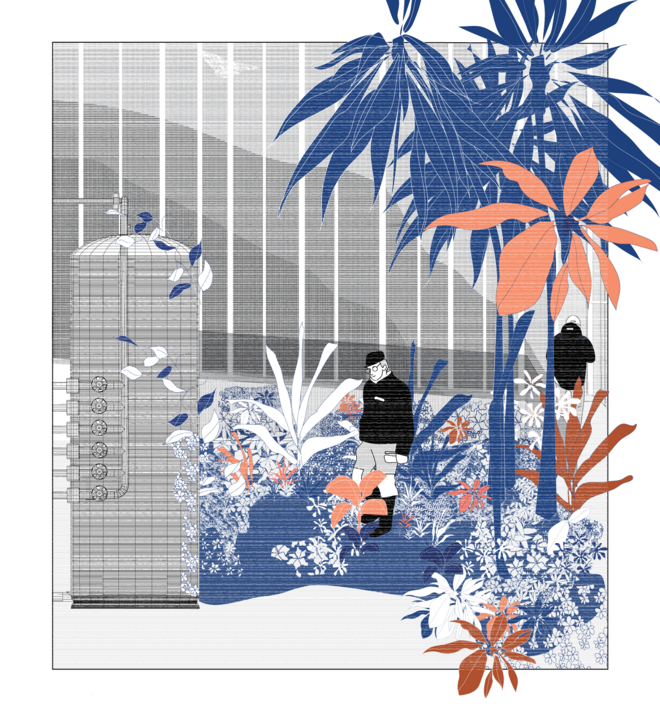

We see architecture as transforming the climate on many levels - at the conscious local level of interior comfortability and also the unconscious global level as the building sector makes up nearly 40% of total CO2 emissions. In extreme climates, weather often produces a hermetic architecture that encloses the interior to account for the extremes. With the role of sustainable architecture coming more into question, and as climates become more dynamic, a new relationship could be explored between architecture, policy and climate that encourages buildings to exploit the transformative aspects of the atmosphere. Buildings in the past have been designed for a life span under stable climate conditions. Now we can see that architecture calls for a new understanding where multiple climate zones and trajectories could be imagined in a hybrid of building, landscape and infrastructure. We took inspiration from the way one dresses in Greenland. Layering is vital to stay warm. And then when it’s too warm, a layer is taken off. Could a building function in this same way?

Making the Invisible Visible

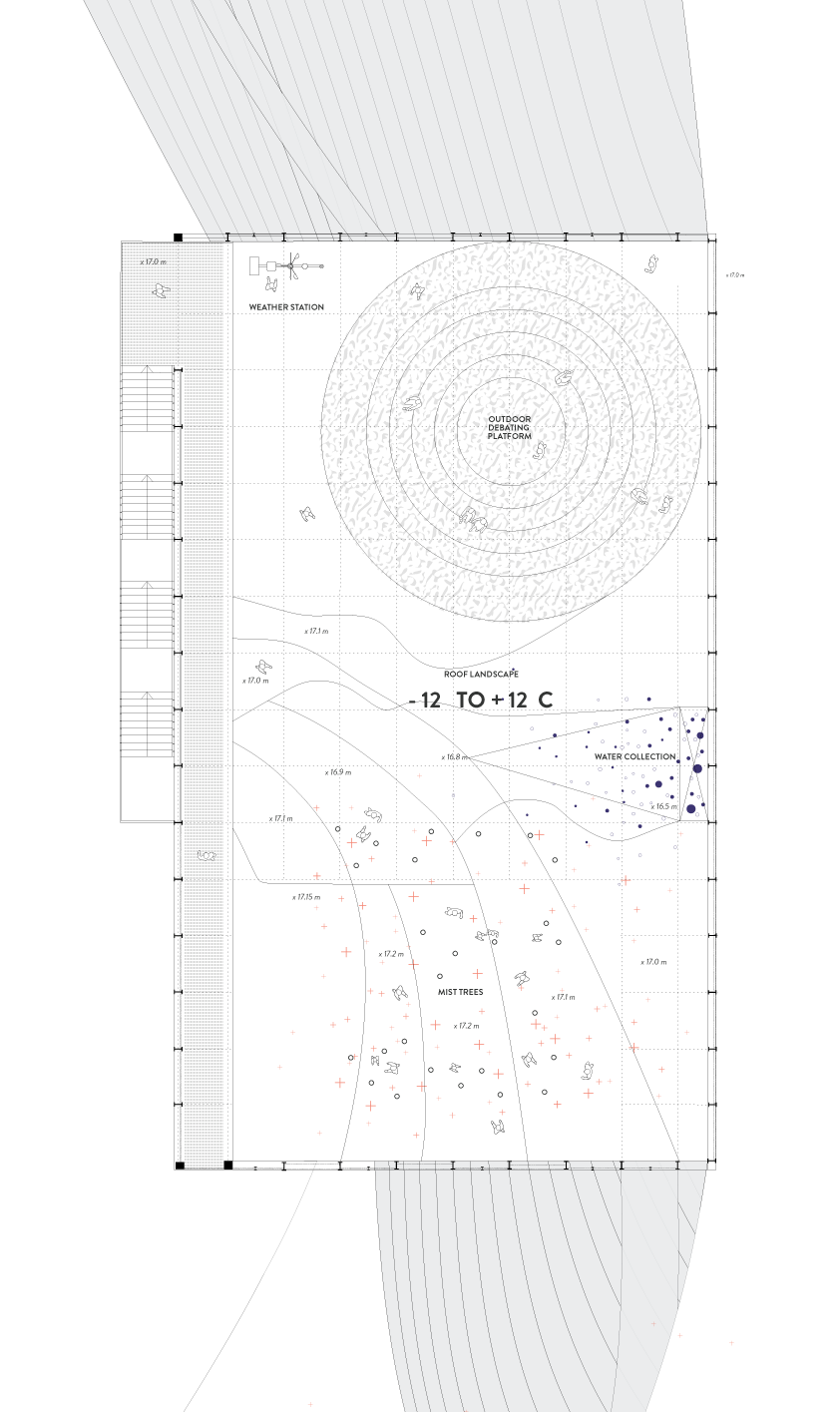

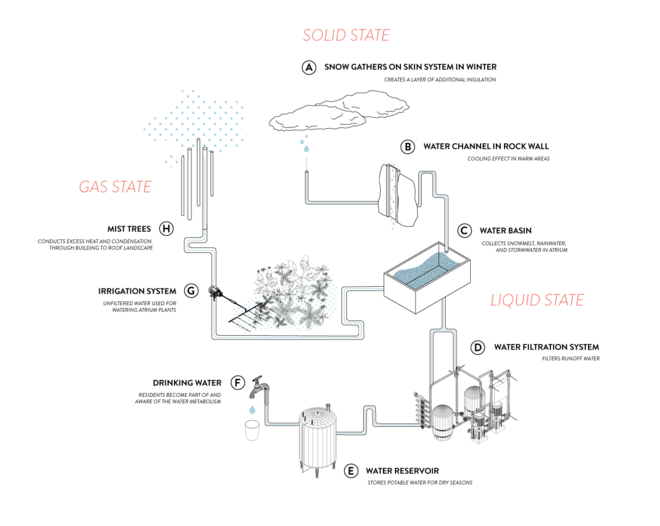

Making visible the changing states from ice to water in our architecture was important to us as a symbolic and functional element, highlighting the anthropocene transformation of this essential global resource. We wanted to use it both as an active element of transforming the climate inside the building as well as to show how it also reacts to the changing climate outside the building. The water climate machine is made up of different elements that we used in our architecture - among them the water channel which runs down the rock wall, the water tank which stores the runoff water, and the mist trees which carry condensation out. These elements refer to the use of exposed infrastructure in Greenland and the pipes we saw running throughout the landscape, creating an awareness of ecological and energetic metabolisms through visibility.

A Future History of Ilulissat

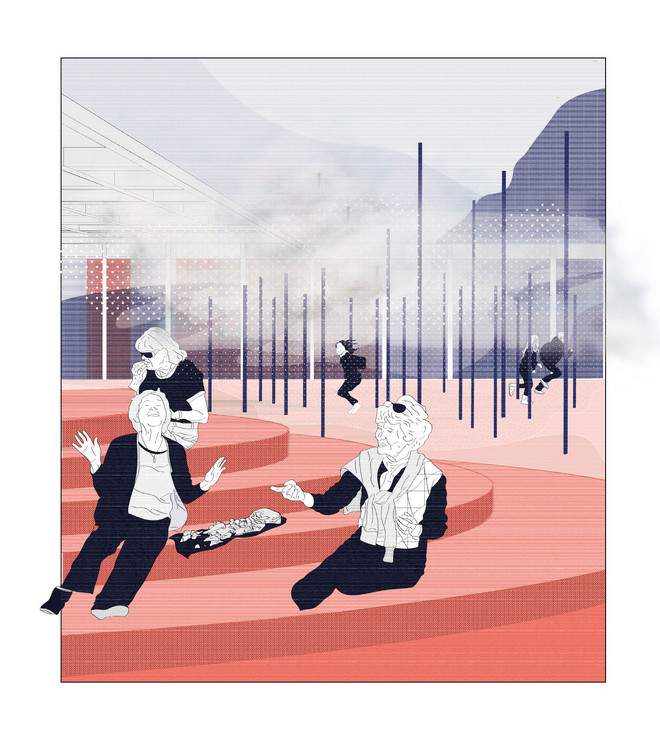

Using narrative and storytelling as a way to both inform and communicate our design, we envisioned a series of speculative future scenarios, their impact, and thereby how to provide for these particular variations. Imagining these future climates allowed us to think about what this could mean on levels of function, space and materiality. We decided to show this range of scenarios, but the idea is that the project could also react to other possible trajectories in an unknown and unstable future.

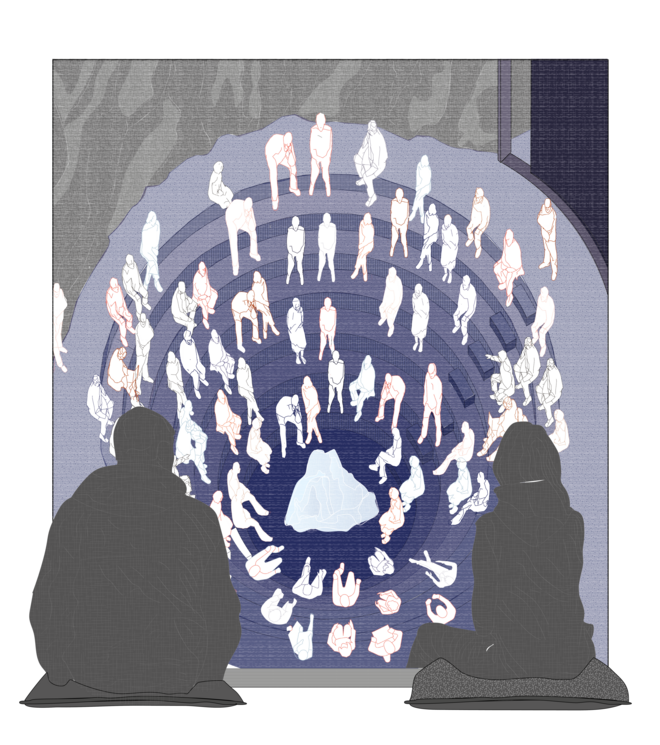

Anthropocene Atmospheres

The project aims to explore the sensory impact of a globally changing environment on an individual level through the layering of climates, meteorological architecture and representations of time - through both artificial and ‘natural’ means. For us this process opened up possibilities of seeing architecture as a larger system that also includes infrastructure, landscape and climate. This is essential in a context like Greenland. But as conditions become more extreme in the rest of the world, could we learn from this and see climatic architecture as tied to awareness and action? To not see architecture as independent from nature but as a part of a larger metabolism that can also respond to shifting states.

Det Kongelige Akademi understøtter FN’s verdensmål

Siden 2017 har Det Kongelige Akademi arbejdet med FN’s verdensmål. Det afspejler sig i forskning, undervisning og afgangsprojekter. Dette projekt har forholdt sig til følgende FN-mål