Dismantling the Veil

This project is set in Chittagong, Bangladesh, but its problematics is of a global nature. It addresses questions of gender inequality, cultural barriers and community. To what extent can architecture change social structures?It opens a discourse of how architects should balance the ordering of the physical and the social in architecture.

Through growth over time the project adapts for future contingencies. The scales are mediating between known safe spaces, and new challenging programmes. The project draws one possible scenario for architecture as a common: An architecture growing out of a women community affecting the gender inequalities, by creating space to make the culturally neglected problem visible.

”The right to the city is not simply the right to access education or work. Rather, it is the right to belong everywhere, to inhabit cities through independent exploration, to influence institutions as well as attain a livelihood.

- Henri Lefebvre

Thesis programme

Objectives:

This project seeks to set a stage, establishing a consciousness of gender differences on and around my site in Bangladesh. My aim has been to develop an architecture that is at once credible and conceptual. An architecture that challenges the social structure with an almost utopian goal, but with an approach so rooted in the local it could be built.

The architectural process has been about a layering of concepts (filtering, enclosing, meeting needs, challenge norms, transmitting zones of dominance and more). In a reciprocal dialogue between programming and designing. It has been about searching for a way to meet the needs while adding something challenging norms, something that strengthen the local women and widens their perspective. Hopefully creating a critical awareness in the women, to make their own choice on how to act.

Premises:

Bangladesh is a unitary parliamentary republic, and it’s constitution is of secular nature. It states that; ”Women shall have equal rights with men in all spheres of State and Public life”. But religion is the primary identity marker in Bangladesh and governs all aspects of the social and personal life. Some of these are seriously restricting half of the population. Rights like mobility, social and sexual liberty and safety. This group are the women. Life for most people in Bangladesh is hard, having to endure these additional restrictions gives little to no chance to alter their life path. One of these social laws is “purdah”; the social practice that ensure women from the male gaze. It can take form as a piece of clothing, but it also extends out in space limiting mobility and movement especially in the public.

On my field trip to Bangladesh I was looking at the vernacular architecture. I visited a range of different typologies for investigation. It became clear that the conformity and injustice also translated into the spatial. For example; the home is a relaxing space for men and a working place for women, a classical tendency in patriarchal societies.

Introduction to Problematics:

The project is set in Chittagong, Bangladesh, but its problematics is of a global nature. It addresses questions of gender inequality, cultural barriers and community. To what extent can architecture change social structures?The project also opens a discourse of how architects should critically balance the ordering of the physical and the social in architecture.

In the programme I asked myself: How can a built environment change the social, the possibility to alter a person’s life path in the context of Chittagong? More specific, what kind of architectonic elements, programs can loosen the dichotomy of private and public space, starting to dismantle the veil in the patriarchal structure?

This initial focus on the dismantling of the boundary between private and public, and how they relate as gendered spaces has widened slightly. I realized that in order to affect this group of women in and around my site, the problem first has to be constructed. Sumita Sinha writes that: “Negotiation is more likely to succeed when the parties concerned understand the reason for the differences in viewpoints. To do this, spaces for education and interaction within the women community of Chittagong became more important. To create the necessary bubble which allows for self reflection. A safe anchor for novel ways of acting.

Community is often the strongest identity marker, especially in a country where the individuation process hasn’t had a very big impact. A challenge and a strength lies in the creation of an alternative community. One where gender can step into focus. Central to the though of this women community is a recreation of the common. As I mention in my text the common enter as an alternative to public and private. Not deciding through ownership who uses a resource, but through a socially interactive governing system. In feminist literature patriarchy is held to be about power over others, while matriarchy is held to be about power from within. It is a transformation from a system that; values hierarchies and ordering, to one that emphasize the relational and the empathic. The community is a relational ordering where the human interaction is at work. An open-minded community is the framework for building a platform for agency, where “Agency is described as the ability of the individual to act independently of the constraining structures of society”. Such communities, I think, would create a more resilient city, a city more responsive and easier to make sustainable, both environmentally and socially.

The cultural barriers of this project is of a precarious matter, being a western male operating with gender issues in a foreign culture. Based on values only somewhat acknowledged in that culture. A position I have held in my consciousness through out my project. Avoiding the trap of ethnocentrism.

Approach and process:

The project has been equally a matter of programming and designing. The kind of change I wished to make is of an inter-human nature. To my understanding a participatory design process would have been the most ethical method, synthesizing the social and the design. In lack of such dialogue I turned to a more classic process where research and references guided my ideas in the beginning. But as ideas materialised I sent a questionnaire to my co-student in Chittagong, who I knew from the collaboration we had with a local university during two of the weeks of the field trip. From here I got a lot of god information from within the culture. I asked her to interview some of the residents around the site. The result was sparse but still gave me a hint that I was on a credible track.

Most of the projects I’ve looked at have a social agenda or are set in a similar socio-economic landscape. They often work with local resources and on the premises of the locals – meeting needs but pushing boundaries.

At the beginning of the design process I reconsidered how and where the square could relate to the enclave. Looking at the urban constitution with the dominant road, I tried to activate the border between the conformed village and the city, braking it, transgressing it, to connect the more private enclave and the public street. But here the project became something dominant, an exclamation mark I did not aim for. My aim was more to meet the local women where they were and bring them from there to show them something new. The radical became uninteresting because my thoughts on radical are born in another, disconnected culture. I have no roots in the locally conventional. There for, I cannot make a revolution against it.

With the outset to make as little intervention as possible I then made a diagrammatic model of a filtering between the street and the enclave. Its scale between building and furniture, and the interlocking spatiality was something I saw as qualities with potential. The elements are specific, a little bit unfamiliar but not intimidating. A spatiality easy to take ownership of.

Robert Evans writes that introducing “new physical systems gives rise to novel action types. ” My system has been a transformation of the niche. Interconnected spatialities leading to new spaces. I have used the rounded shape to invite, lead through and embrace in a series of compositions and situations.

To be credible, there is a need for a balanced reflection of components. Meaning that questions like; how will the project be funded, how can real social change take place, how many interventions are needed to make an effect etc., all has to be considered.

Time is a field letting us experience the effects of our actions. A tool to modify unforeseen outcomes, accommodate new needs and enhance successful interventions.

Therefore I have chosen to look at the project as a couple of scenarios. The first being how I imagine a participatory design process could be carried out and secondly what kind of programs and architecture this could generate. Another aspect of time is permanence. I have tried to let the architecture have a differentiated degree of programming. The more permanent elements being those which can manifest the programmes. A way to protect the fragile interlinked programmes from falling into the wrong hands. The scenarios need time to become reality, something a differentiated permanence could help secure.

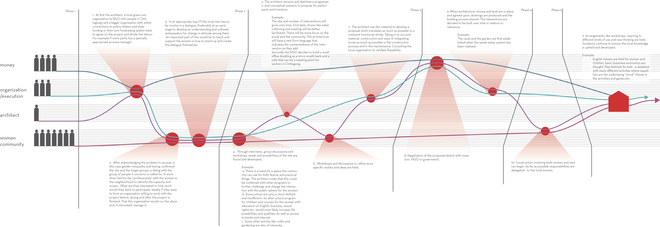

Briefly, the first scenario suggests a cooperation of either the state or a economically strong organisation, with a locally rooted NGO working with social development, an architect and of course the women from and around the enclave.

Scenarios of Architecture:

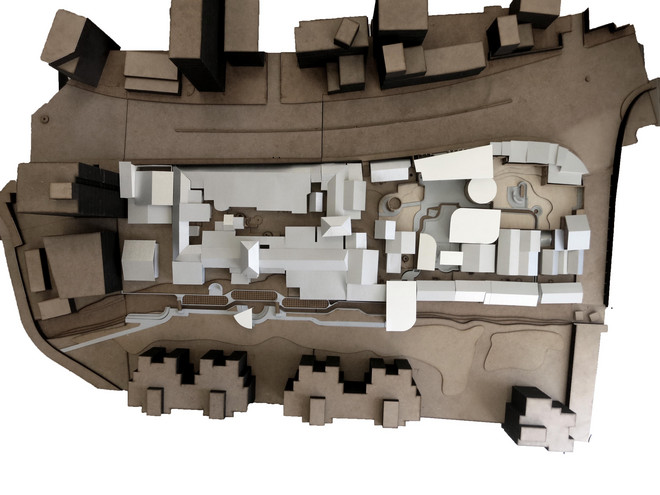

The second scenario is about the architecture. A scenario composed of many different parameters. Dealing both with the social aspects and more practical aspects.

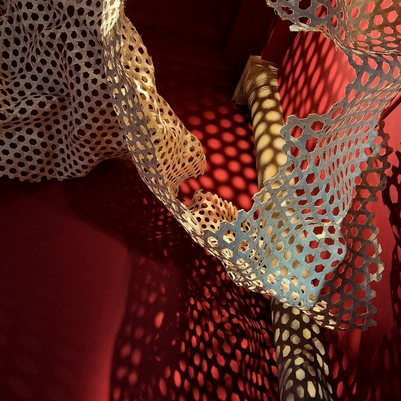

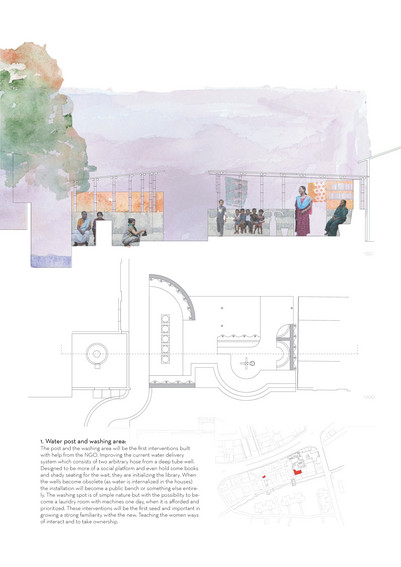

The first interventions to be built, with help from the NGO, are two new water posts and a washing area. Improving the current water delivery system which consists of two arbitrary hose from a deep tube well. Designed to be more of a social platform, holding some books and shaded seating, they are initializing the library. These interventions will be the first seed and important in growing a strong familiarity with the new architecture. Teaching the women ways of interacting and to take ownership.

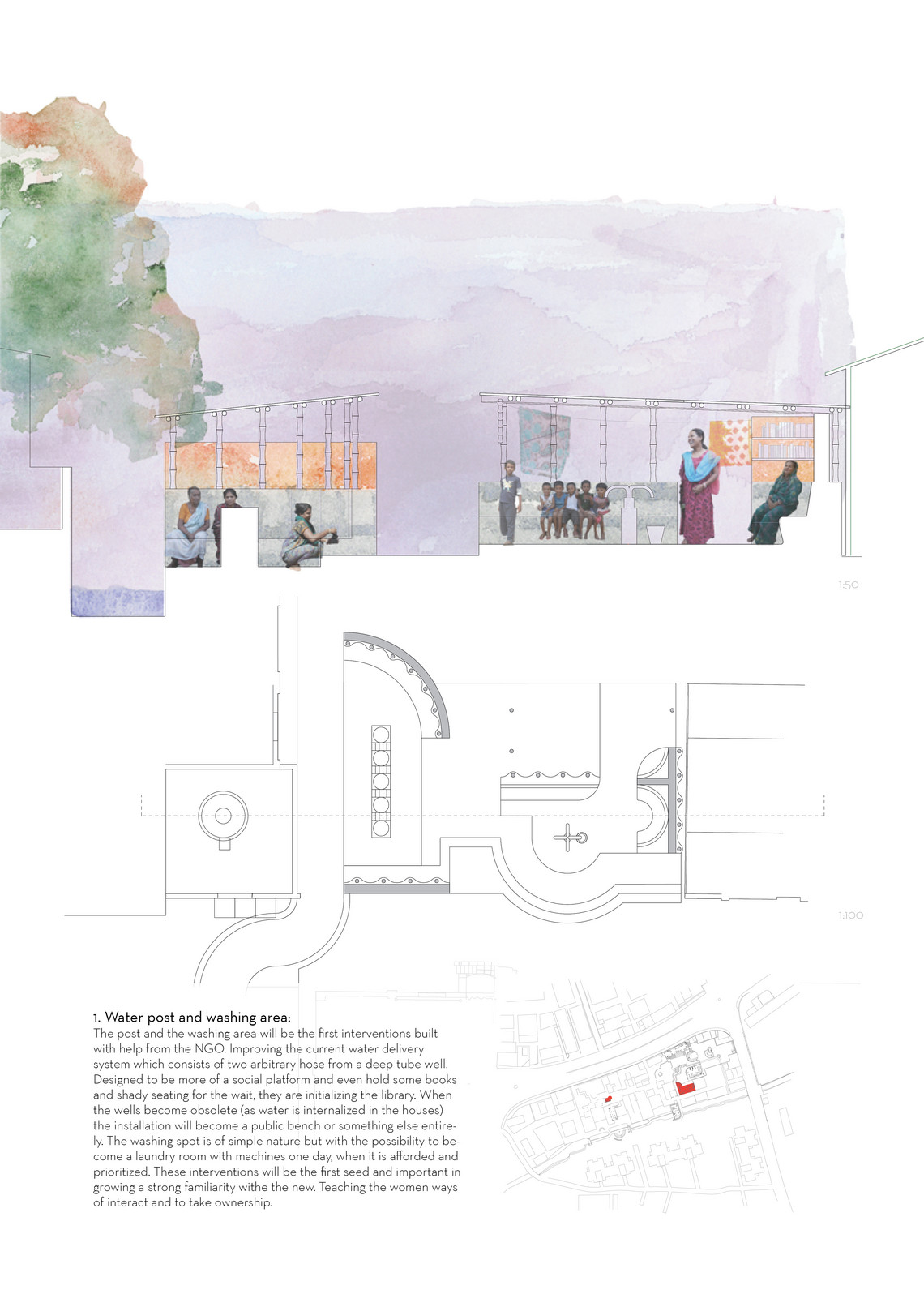

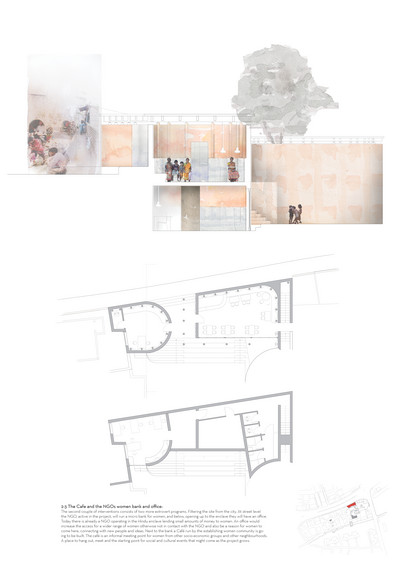

The second couple of interventions consists of two more extrovert programs. Filtering the site from the city. At street level the NGO, active in the project, will run a micro bank for women, and below, opening up to the enclave they will have an office. Today there is already a NGO operating in the Hindu enclave lending small amounts of money to women. An office would increase the access for a wider range of women otherwise not in contact with the NGO and also be a reason for women to come here, connecting with new people and ideas. Next to the bank a Café run by the establishing women community is going to be built. The café is an informal meeting point for women from other socio-economic groups and other neighbourhoods. A place to hang out, meet and the starting point for social and cultural events that might come as the project grows. It appears very modest from the street where it is visually enclosed, but it can be opened up towards the back. Only the passage between the café and the bank makes an inviting gjesture. Sections of the walls are perforated on both sides of these buildings, enabling to look out, but not in. Like the interventions in the enclave the roof structure is in negotiation with the social spaces. But here terracotta clad pillars are carrying beams of laminated bamboo instead of the more conventional bamboo structure used in the enclave. The structure is also set on the inside of the wall, suggesting an introvert social focus. Whereas in the enclave the extrovert structure affects its surroundings with this social gesture.

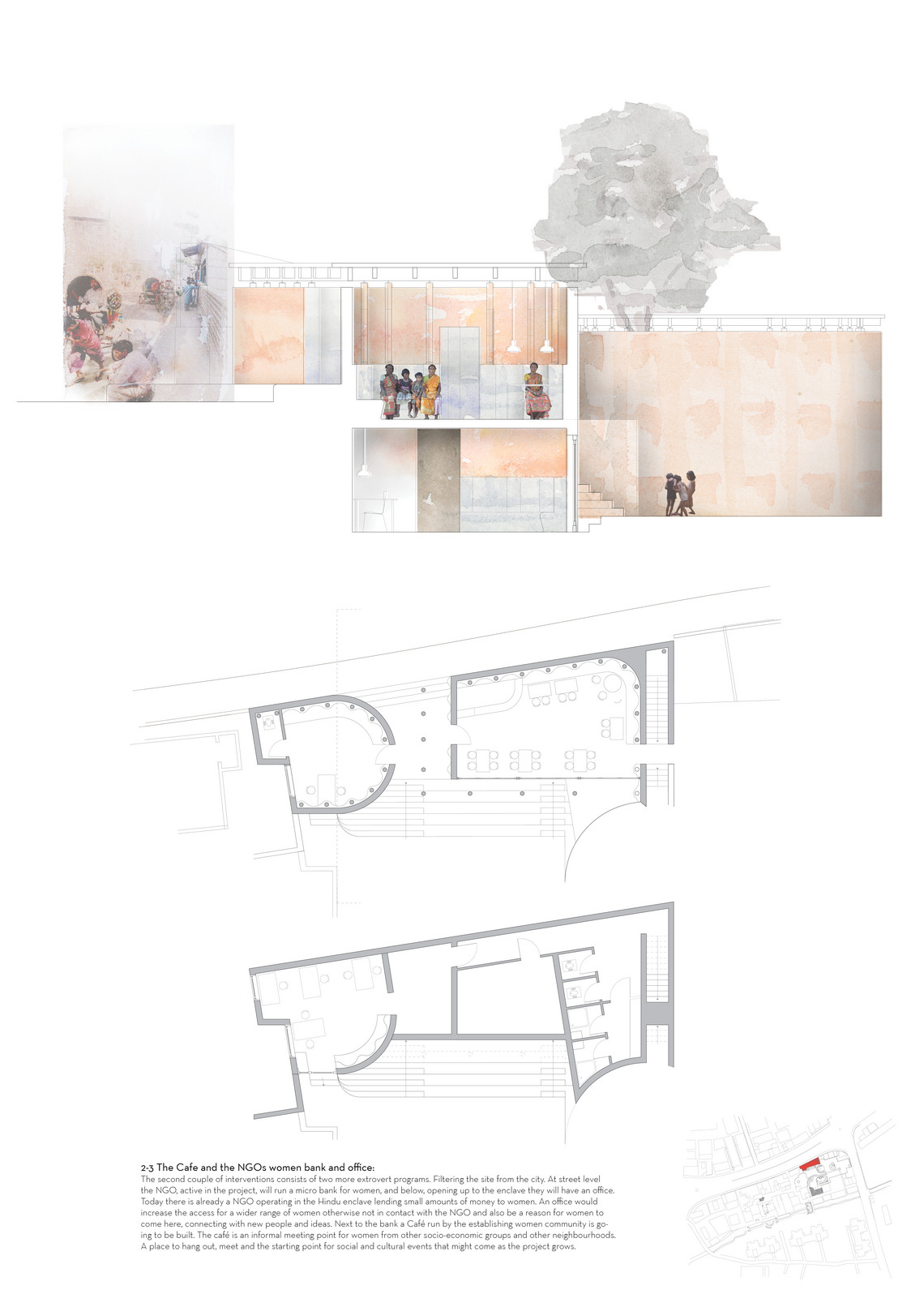

The fourth intervention is the Library. When the book corners by the water posts become inadequate, there is time for a library. Here, women from the women community and their children, can read and access books, internet and other relevant media. They can come here just for fun or to get information for a class or workshop they are attending. A few women works here and manages it with help from the NGO. The building has a similar scale and is of similar materials as the surrounding homes but has a different form language indicating something new. It holds many niches and corners easily inhabitable by one or a few women, further developing the benches and thresholds I found in the enclave. The backside together with the existing houses form a small slack space to be inhabited as they wish.

As a programmatic extension to the library a bridge with a class room is built, connecting the two different enclaves. Here the women and children can be thought to write, learn English or have courses in household economy. There are also small “caves” for children where they can read, relax or play. The children can be an excuse for the women to come here if their husbands disagree.

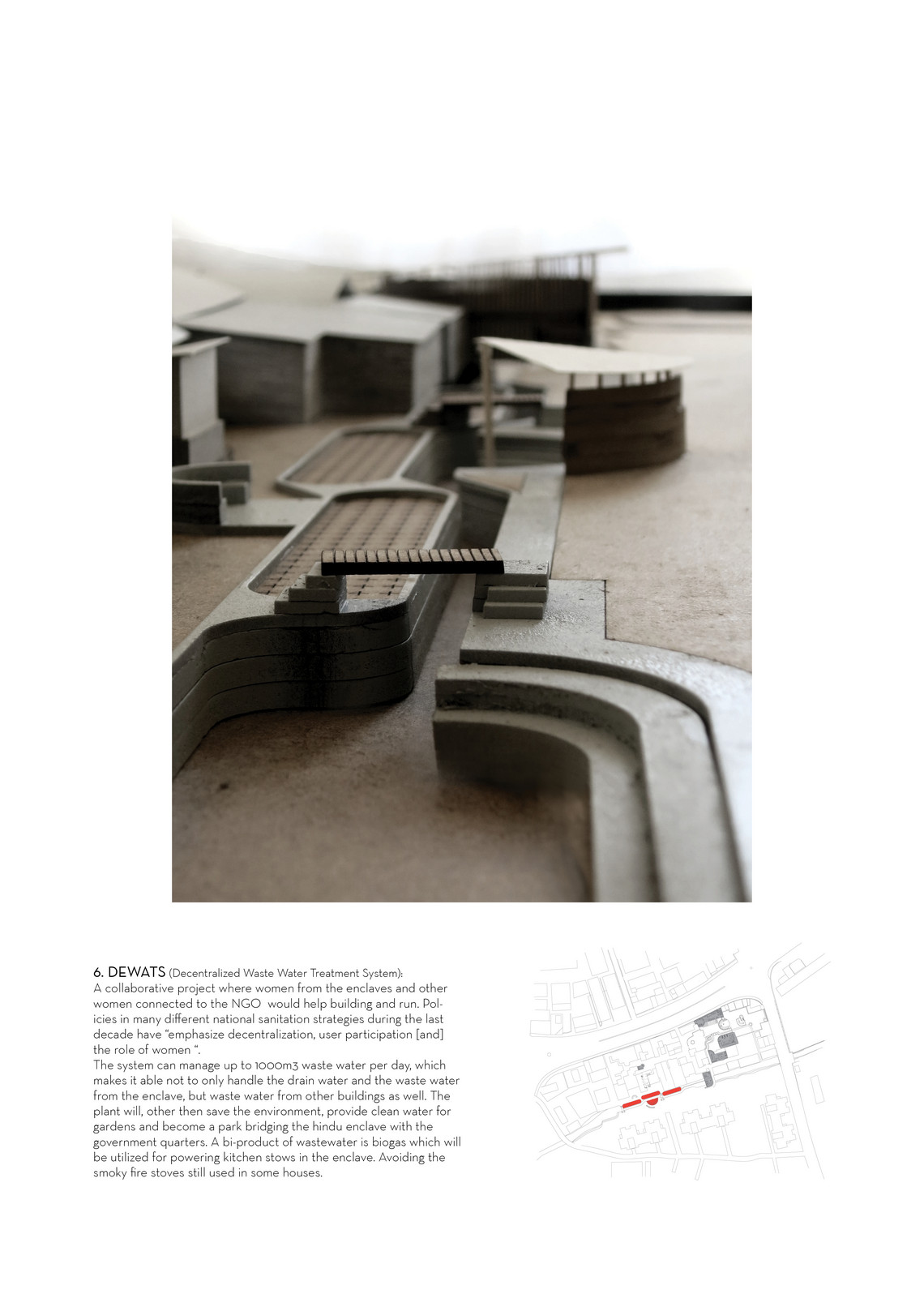

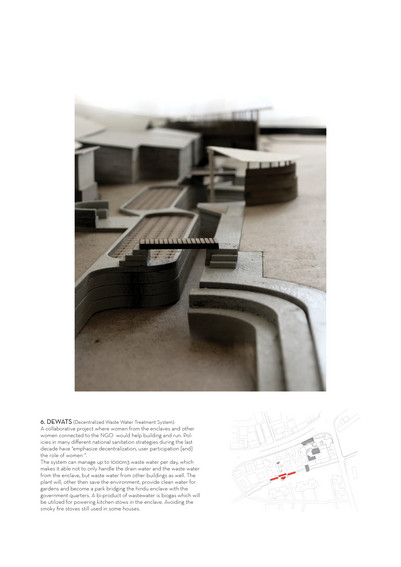

With the new access to the ground of the government quarters, a collaborative project where women from both the enclaves, and other women connected to the NGO, would build and take care of a decentralized waste water treatment system (DEWATS). The collaboration of this semi public park, would strengthen the women community.

Policies in many different national sanitation strategies during the last decade have “emphasize decentralization, user participation [and] the role of women “. The system can manage much more waste water then the enclave produces, making it a resource for the municipality. And a bi-product of the wastewater is biogas which will be utilized for powering kitchen stows in the enclave. Avoiding the smoky fire stoves still used by women in some houses.

The park becomes a recreational space with informal seating, shade and a connection to the water.

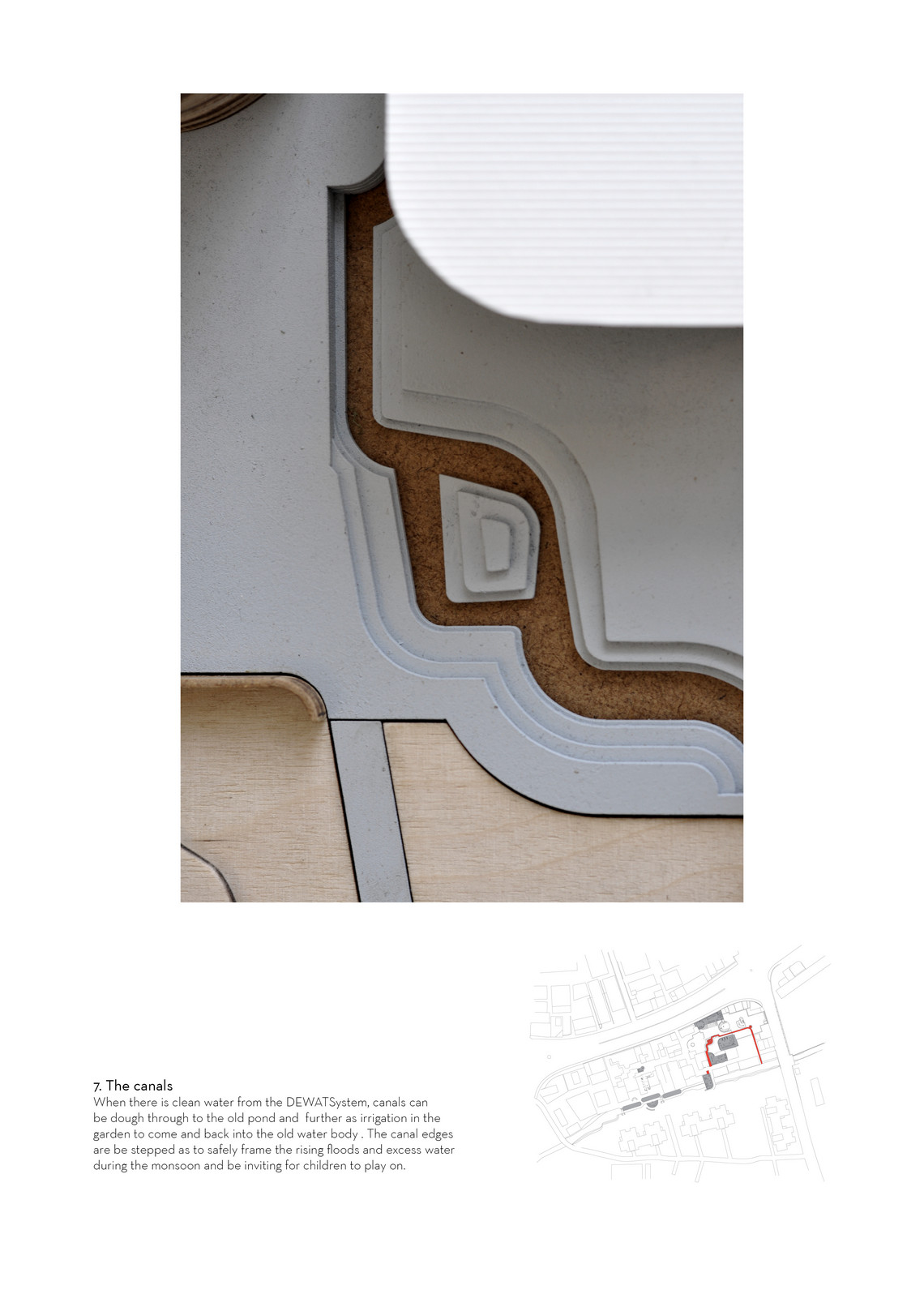

When there is clean water from the DEWAT system, canals can be dough through to the old pond and further as irrigation in the garden to come and back into the old water body . The canal edges are stepped to safely frame the rising floods and excess water during the monsoon and be inviting for children to play on.

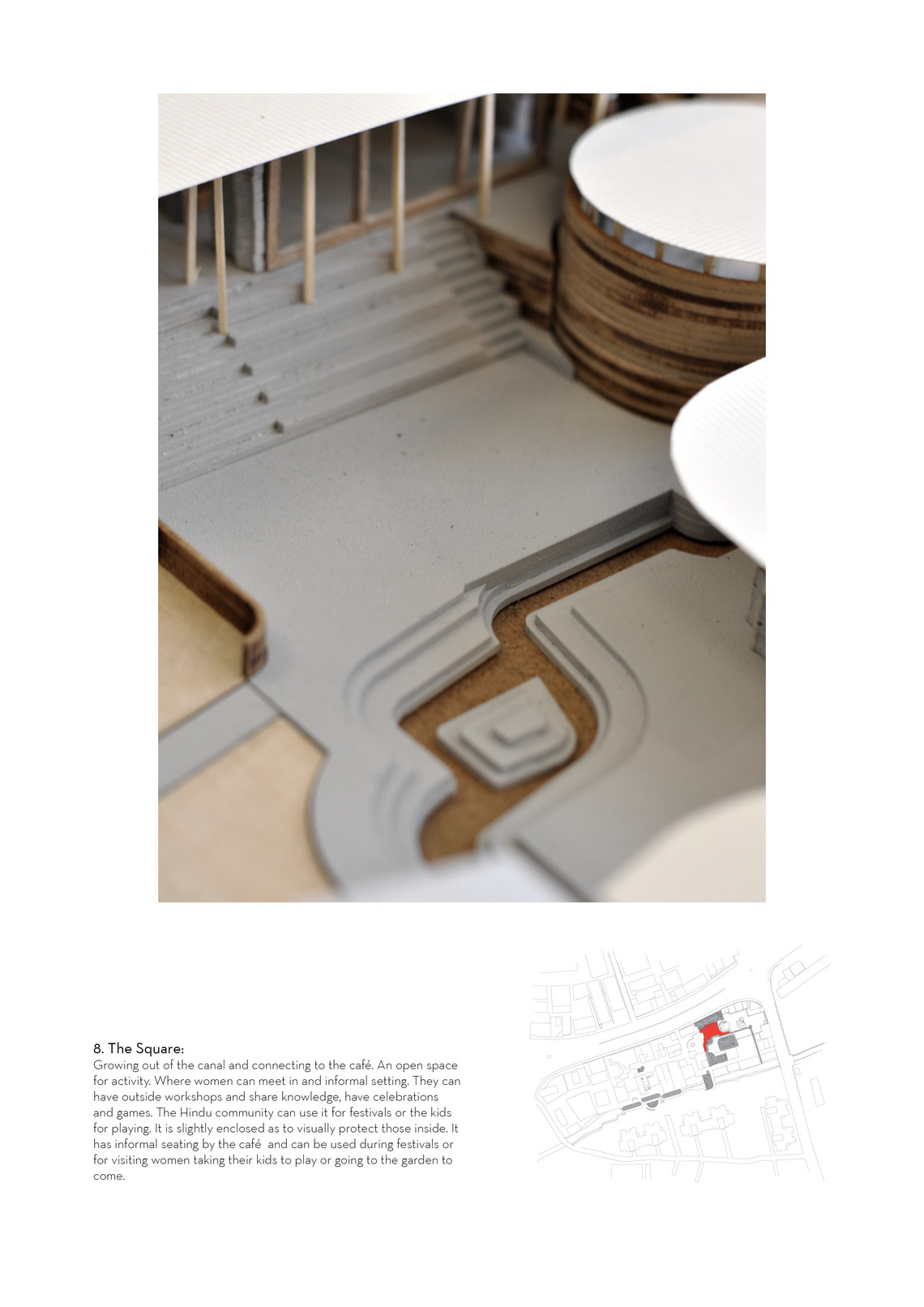

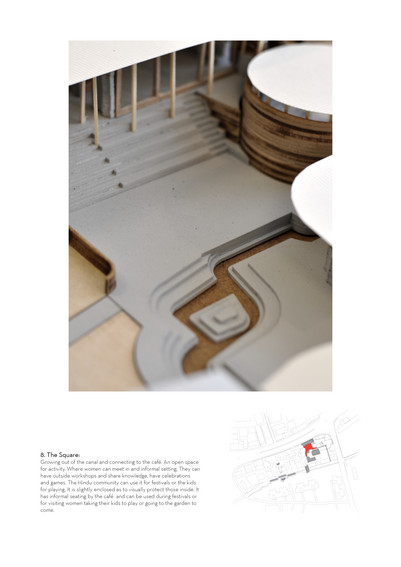

Growing out of the canal running through the pond, and connecting with a tribune coming down from the café; A square is built. An open space for activity, where women can meet in an informal setting. There is space for having outside workshops, celebrations and games. The Hindu community can use it for festivals or the kids for playing. Visually it is slightly enclosed to protect those using it. This might become the actual negotiation space between men and women. Unprogrammed and public, but surrounded by women related activity.

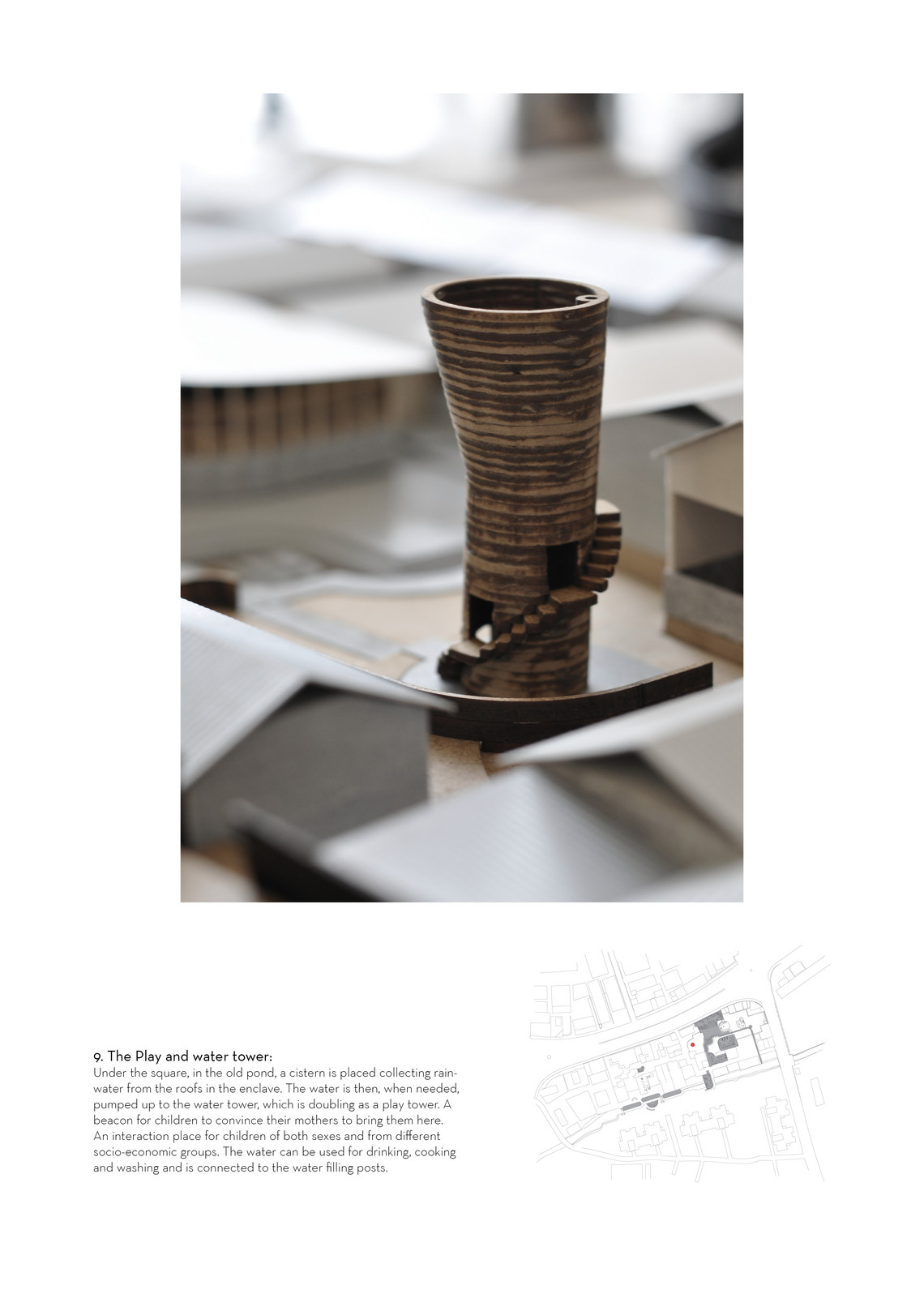

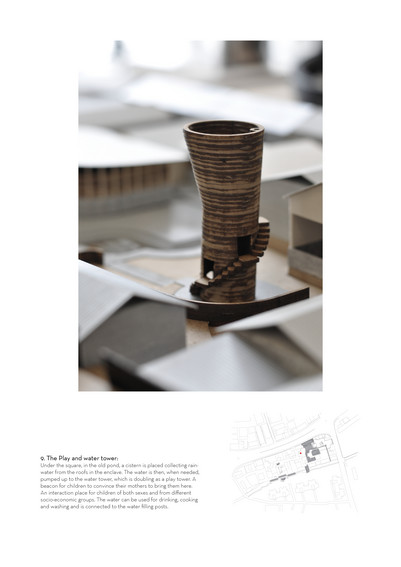

To further appropriate the square to women, making the locals and visitors meet and utilize natural resources on the site, a water and play tower is built. Under the square a cistern is placed. Collecting rainwater from the roofs of the enclave. The water is then pumped up to the water tower and used for drinking, cooking and washing. A small spiral stair for children runs up around the tower. Entrances leads to different levels of pensile playing nets. At the top is a vantage point overlooking the area. The tower can hopefully become a beacon for children, convincing their mothers to bring them here. A place for children from different socio-economic groups to interact.

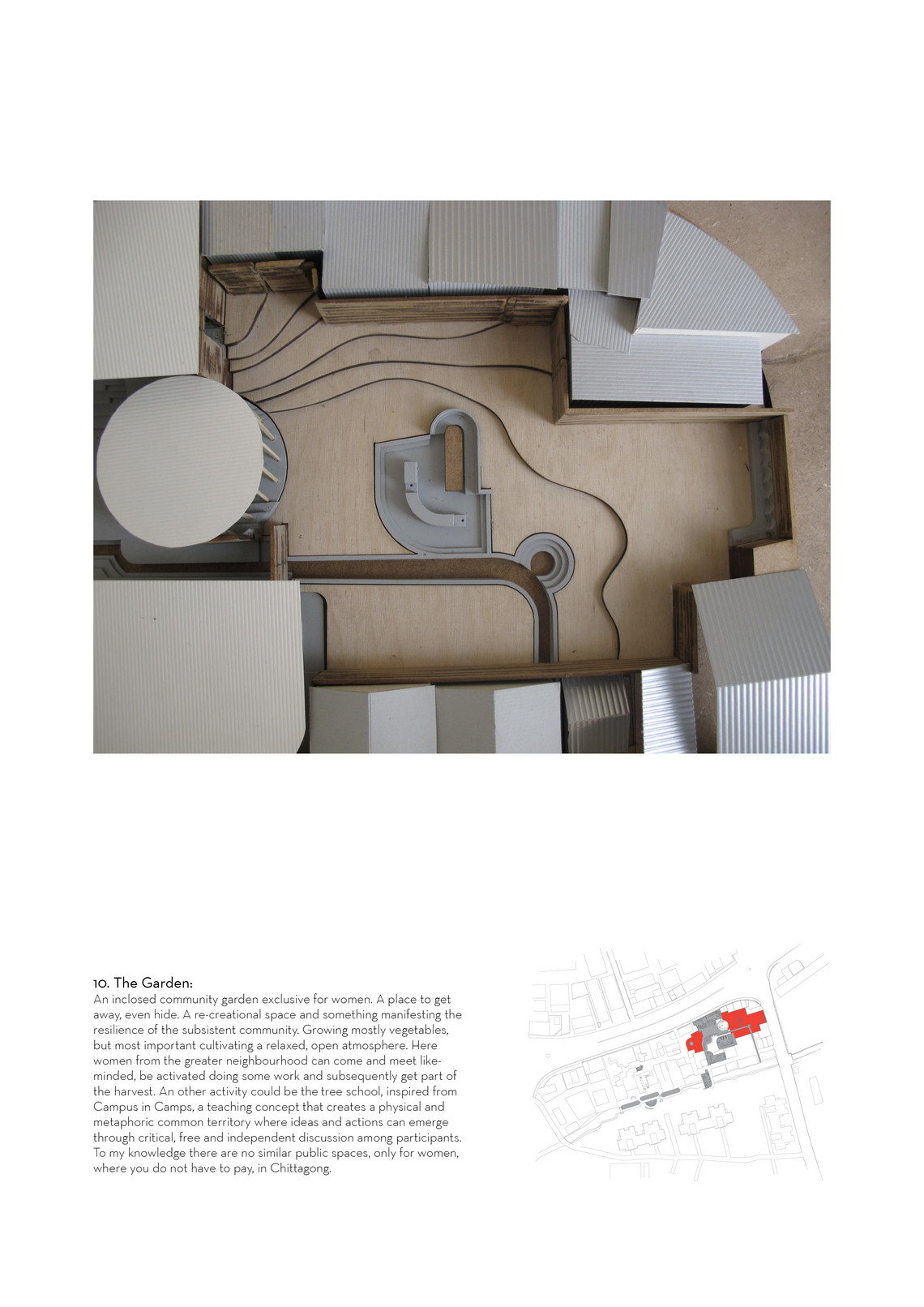

With water from the DEWATS, an enclosed community garden exclusive for women is laid out. A place to get away, even hide. A re-creational working space for the community. Growing mostly vegetables, but most important cultivating a relaxed, open atmosphere. Here women from the greater neighbourhood can come and meet likeminded, be activated and learning about gardening. An other activity could be the tree school, inspired from Campus in Camps, a teaching concept that creates a physical and metaphoric common territory where ideas and actions can emerge through critical, free and independent discussion among participants. To my knowledge there are no similar public spaces, only for women, where you do not have to pay, in Chittagong.

In the garden, slightly recessed in the terrain a community kitchen is established. A place for the women of the enclave and other women to cook together for a festival, for fun or if they are just bored of their own kitchen. An informal way of making friends and using the freshly harvested vegetables and herbs from the garden.

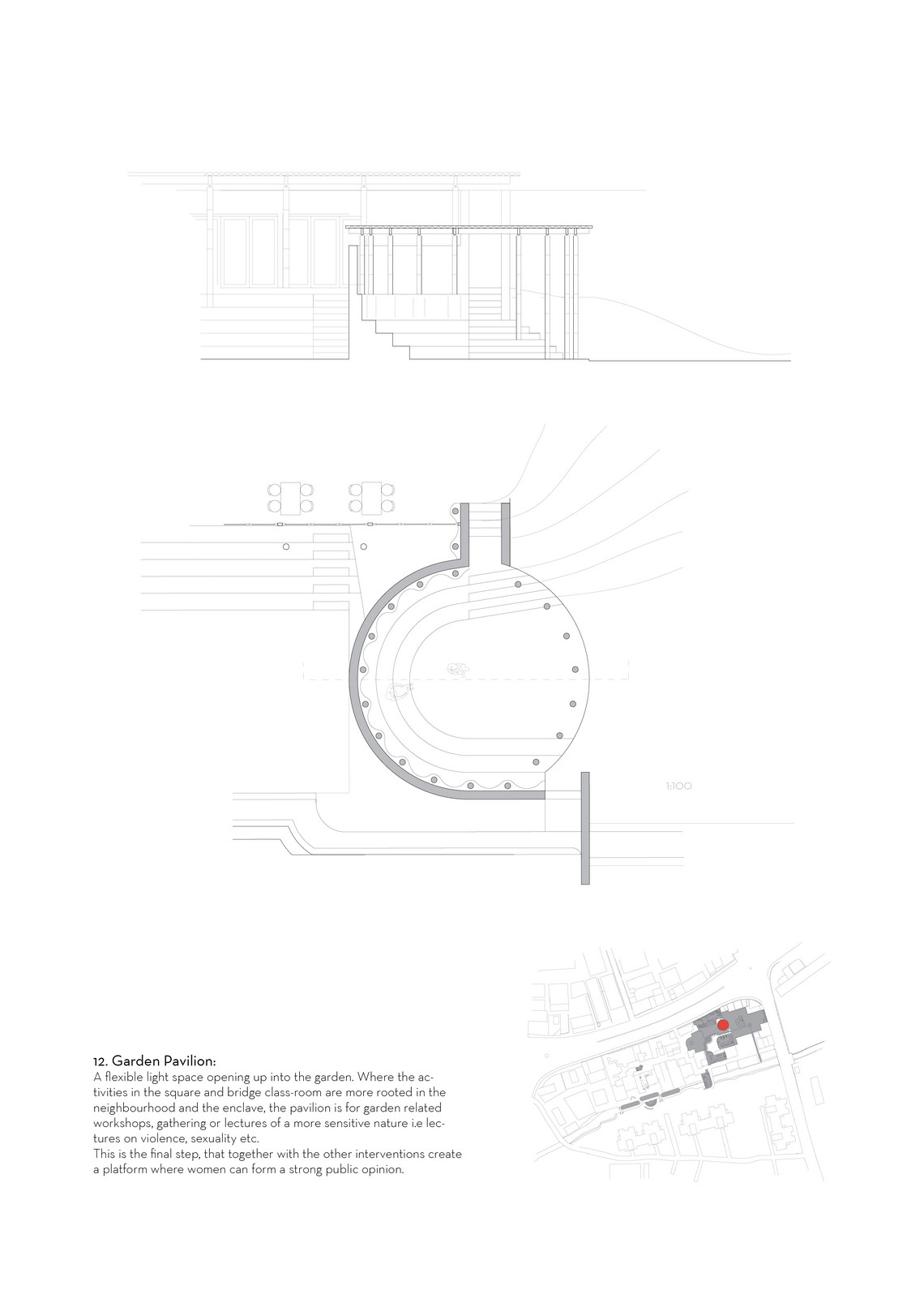

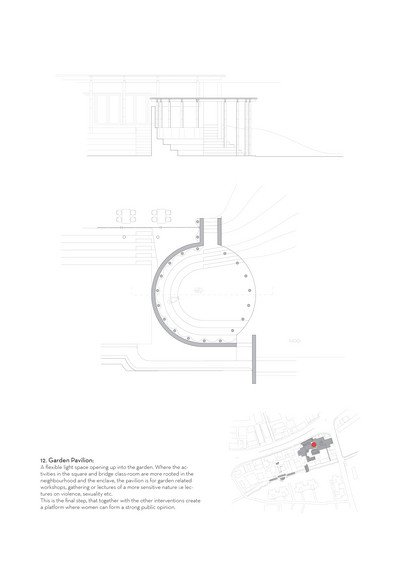

Between the square and enclosing the garden a pavilion is constructed. A flexible light space connecting to the café and opening up into the garden. While the activities in the square and bridge class-room are more rooted in the neighbourhood and the enclave, the pavilion is more of an extension of the café for gathering or for lectures of a more sensitive nature for example about gender violence or sexuality, but also for garden related workshops. Here the two worlds meet, the enclave and the city, in a female public space.

This is the final step of my scenario, that together with the other interventions create a platform where women can form a strong public opinion.

By creating an architecture negotiating between the physical and the programmatic, between structure and social spaces in its tectonics, between the known ways of spatial use and the new ways of use, I hope I have in some ways started bridging the gap between my political agenda in this project and an architecture affecting change in the social structure.

I would like to clarify that even though my values and ideals have been the drive in this project. The project does not try to superimpose these values on the women in Chittagong. It tries to simply create space where these values can be seen and critically investigated for then to be dismissed or adopted.

Investigative text:

As a way to inform the project alongside the architectural process I have conducted an investigation through thinking and writing giving me new angles and perspectives.