Mind the Gap! On Drawing and Becoming. Outline for a Philosophy of Drawing

There are two main meanings of the noun ’drawing’: it can refer to a practice, or it can refer to an object. But drawing is not only the action and the object. Drawing is also what happens in the gap between the two meanings.

The thesis can be found here (it's in Danish).

Abstract

Abstract

There are two main meanings of the noun ’drawing’: it can refer to a practice, or it can refer to an object. But drawing is not only the action and the object. Drawing is also what happens in the gap between the two meanings. In that gap we find the concept of ’drawing’, the substantivised verb containing the object and the process in one. Someone is drawing, something is drawn, and something appears. All this turns into an image. Something comes into view through the process of drawing and the result is ’a drawing’, understood as ’a picture’. Something has appeared for the person who draws. It appears while drawing, but also when the drawing is finished – when it has become an image. The image represents an idea, a statement, an expression; a new object and a new meaning have come into existence. The drawing not only appears on paper but also in the subjective or collective conception of the world. Thus, a drawing is always an emergence of a conception, for the artist as well as for the person who sees the finished drawing. But conceptions change through drawing, since in most cases the drawing shows the artist something other than he or she had originally imagined, regardless how vivid the imagined image was. Artists say that the drawing begins to ’think’ or ’speak’ to him or her, that is, the drawing gives something back, and a generation of meaning appears regardless of the artist’s intentions. The artist may feel that the image draws itself and even lets the artist know whether it is finished, is on its way – or has failed. But when we say that the drawing speaks we are trying to cope with the mute appearance of drawing by attributing a metaphor to it. Drawing can spark thinking, but the drawing itself, understood as the concept of drawing, lies outside the field that we normally define as language. It leads us to the question: How can we speak about the space where the drawing emerges?

Trying to penetrate the statement of the drawing is the focal point of the dissertation, not in order to demand an answer or a voice but in order to draw attention to its existence: to the language of drawing – to drawing as drawing. In the thesis, drawing is situated in the space between a transition, an image, an action and a thought and seen as an opportunity to expand the world. In a sense, the thesis revolves around a specific perspective on drawing. The perspective looks at drawing as emergence. I explore this perspective through analyses of my own and others’ practice and by examining how it can be related to relevant philosophical discussions. The dissertation should be seen as a contribution to a discussion of the concept of drawing: What do we mean when we say ’drawing’?

The thesis is conceived in three parts. In the first part I give an overview of the status of drawing research today and describe how my own research relates to it (Chapter two). The second part addresses the philosophical basis for the development of emergence as the idea of drawing (Chapters three and four). In Chapter four, careful readings of Henri Bergson’s concept of intuition are related to Gilles Deleuze’s and Felix Guattari’s philosophy of immanence. These readings lead to Giorgio Agamben, with whom I discuss the concepts of ’praxis’, ’poiesis’ and ’potentiality’. The third part encompasses the more empirical studies (Chapters five, six and seven). In Chapter five I analyse three examples where artists in the twentieth century have worked very explicitly with drawing as emergence: the American painter and writer Robert Morris (1931-), the Belgian writer and painter Henri Michaux (1899-1984), and an artist who is outside the usual definitions of art/design/illustration, namely the Swiss healer Emma Kunz (1892-1963). In Chapter six, I analyse drawings by two students at the Danish Design School in a class called ’drawing laboratory’, a class that I initiated myself. Finally, in Chapter seven, I discuss my own work with a series of drawings, which I did before I embarked on my Ph.D. study. In all the empirical studies I aim to see the drawing process from the point of view of the creator and investigate what premises the specific drawings have emerged from. Thus, the argument moves from the most general perspective in the chapter on drawing research to a philosophical discussion and further on through an analysis of the works of others to conclude with a subjective approach with a phenomenological experience orientation. The ongoing discussion throughout the dissertation is whether it is possible – at all – to render a tacit process. The dissertation speaks at the edge of this taciturnity.

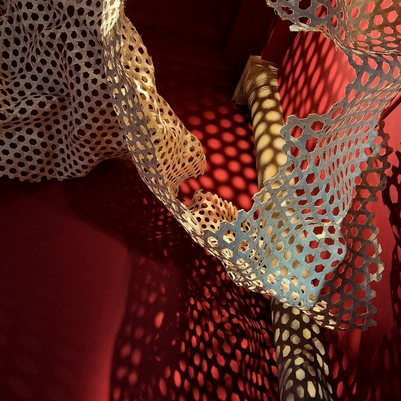

In the understanding of drawing that I arrive at, drawing can simultaneously make the world appear and create a chasm, a lack of meaning. Drawing creates (and in my opinion must create) an abyss to the same extent as it creates itself, as it always points to what is missing, both through the exclusion of what is not on the paper and through the enunciation of itself. In this enunciation of itself, in its potentiality, drawing escapes its own definition. The drawing of the drawing not only creates a clarification but also endless tracks and holes in the world. These absences and tracks are the essence of the quality of the artistic language. Drawing is a way for us to relate to this quality.

If we take our point of departure in this paradox, drawing and drawings are not a way of depicting but of relating to silence and potentialities. Drawing and drawings establish a relationship. The main contribution that this thesis provides to the discussion of drawing and emergence is that it points to exactly this condition. It is a relationship that I think is generative and one reason why drawing continues to be a part of the artistic disciplines. In this interpretation, one may see the drawing as a picture of the nature of art. My conclusion is that we have to welcome the paradox. We must accept that any production of a drawing is also an evasion. A drawing is not a piece of ’extra’ consciousness, but the drawing is able to shape consciousness, and in the consciousness, shapes and formations of silent gaps constantly occur.

Looking at drawing in this way has consequences for drawing education. In previous arts education programmes, drawing education held a central position. Teaching was usually based on classic observation disciplines. Today this discipline has been replaced with exercises in conceptual thinking, – especially in design schools. This kind of visual thinking is diagram-based and ruled by the queen of concept development: the yellow Post-it note. I believe, however, that the imaginative power of drawing continues to hold opportunities. Through drawing the students have the opportunity to experience genesis in a very concrete way. And they learn the premises for stepping into the artistic realm.

A line appears not at a glance; it begins, ends or continues – it is temporal. What is drawn is drawn in time, and it is drawn while it is being drawn. There is no difference between drawing and appearance. Drawing draws the line, and this line figures its own ground. We must look at the ground with the same vision and in the same vision as the line. If we leave out the distinction of figure/ground, we see appearance, we see the image as a substance becoming. What is drawn is a drawn substance. It has no cause but creates sense. In this sense it creates an abyss.