Coronablog on the Periphery | Kirsten Marie Raahauge

CORONABLOG ON THE PERIPHERY VIII:

THE WOLVES, THE RATS, THE COCKROACHES AND THE VIRUS

For many years, I have been thinking of the quote by Jean Baudrillard about the enemies of the city, the wolves, the rats, the cockroaches and the virus. For years, I haven’t been able to rediscover the actual quote. Now, I have found it, in a collection of “uncollected interviews”, in the book The Disappearance of culture (2017). It is a tiny text bit in the middle of an interview, not, as I mistakenly recalled, part of a large theoretical apparatus. Furthermore, it turns out that the quote is about terrorism and the media, and the impossibility of “direct political action” in France in the 60’s and 70’s. I thought it was about the implosion of culture and the advent of hyper-reality. In a way it is also about these topics, since of course the political is connected to the societal diagnosis of hyper-reality established by Baudrillard.

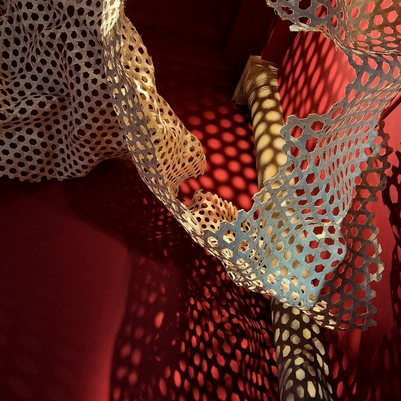

The text bit also deals with disparate waves of enemies, threats and dangers in a spatial perspective, since it describes how these enemies change position over time from a spatial position outside the city walls to a position within the bodies, where reference to space becomes absurd. The enemies shift and move through spatial membranes and layers: ‘the wolves’ outside the city wall, ‘the rats’ inside the city wall, ‘the cockroaches’ inside the houses, and in the end ‘the virus’ becoming integrated into our bodies.

This discussion is a discussion of politics, as noted; furthermore, it is a discussion of the proximity of threats. In other words, from a new perspective, it adds to the discussion about the state, also the welfare state, as a survival unit, raised by Lars Bo Kaspersen (2013) in Denmark in the World, through Norbert Elias’ notion ‘survival unit’. And it is a discussion of ‘risk society’, as seen from a spatial perspective.

Although highly relevant, in the contemporary debate the interconnectedness of welfare systems and space is suffering under amnesia; space is most often not part of welfare discussions and vice versa. Space is never innocent, since it shapes the social systems that it is part of. Being part of the political, the social, the imaginary, the economical and all the other systems that we live by, space is very much present in real life. Baudrillard indirectly discusses space and politics, and he implicates that the enemy which the survival unit tries to defend its citizens against step by step become part of the very same unit.

So, the text bit by Baudrillard might have become relevant due to the days of corona-virus-survival-unit-defense-actions, but at the same time, the topic points to intriguing ways of dealing with space and welfare: the image suggests that although welfare might be protecting us against evil, as Beveridge (1942) claimed back in post war England, the enemy is also inside the welfare system. This might be part of the story of the relationship between welfare and space, for example when welfare amenities are unevenly spread in order to prevent evil, while also causing other kinds of evil.

More in line with Baudrillard’s own philosophy is the perspective concerning the vanishing of space; as the enemy creeps into us, not being wolf anymore, now becoming virus, it adjusts to our organism, and the idea of concrete spatial defenses to threats becomes pointless. Furthermore, it is not only the threat, it is also the welfare system itself, the survival unit that has become internalized. We are our own defense work, being adjusted to the welfare system we live by, and our internalized welfare system is part of the reason why the outer welfare system is capable of working so smoothly. As Baudrillard asks: “The enemy? Who is that? Who?”

Background text

Jean Baudrillard: Terrorism and the Media, pp109-110:

“An answer to a question about the power of the Left that had gone in the 60s and 70s France. Baudrillard explains that the intellectuals made a radical critique of politics and the media, and that the Left never accepted this. He continues:

Direct political action was no longer possible. We were left to do the same thing the terrorists do: destabilise. This results from a genealogy of enemies. In the first phase the enemy was frontal; the aggression of wolves. Then the enemy went underground; the enemy there is like rats. It’s a new state of things, and you can’t use the same strategies of defense against rats as you do against wolves. But people invented new strategies. And then, in the third phase, there were cockroaches. The rats operated in two-dimensional space, but the cockroaches operated in a three-dimensional world. You couldn’t defend against them with the same defense against rats. So, they have invented other ways to deal with this new sort of enemy. But then enters the fourth phase: viruses. And viruses operate in the fourth dimension, which is no dimension. They have not yet the strategies to oppose tis new aggression. They don’t even know the faces of the enemy.

So all former strategies, whether antagonistic-frontal or underground-subversive, are no longer valuable. There is now only the question of destabilization. The first phase corresponds to war; the second to insurrection. The third is some kind of underground subversion, and the fourth phase – the viral phase – is the phase of destabilization. And in this context, we are all confused, whether we talk about the political or the transpolitical. However, the point would be to at least take account of the new dimension and act no more as political subjects because that does not confront the enemy. The enemy? Who is that? Who?”

Baudrillard, Jean 2017 Interview 6. Baudrillard Shrugs: Terrorism and the Media, pp109-110 in The Disappearance of culture. Uncollected Interviews. (Eds. Richard G Smith & David B Clarke). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Beveridge, William Henry 1942 Social insurance and allied services: report. New York: Macmillan.

Kaspersen, Lars Bo 2013 Denmark in the World. Copenhagen: Hans Reitzels Forlag.