Urban Flow—scapes

Imagine water flowing through trenches in the streets of Copenhagen.

A vibrant flow—scape made visible and accessible to the agencies present within the urban environment.

A theoretically oriented thesis

This thesis employs the concept of research about, for, and through design to iterate between a theoretically oriented and a design-oriented study.

RESEARCH QUESTION: How can a reactualisation of the trench not only challenge the concealed infrastructures of rainwater management but also serve to enhance the relationship between urban water systems and the agencies that reside within the urban environment?

Introduction to the project

Water has in recent years become a source of worry as it forces us to rethink the way we plan and design our cities. The storm surges predicted to occur, and the ones already happening, are treated as a hazard that needs to be diverted and controlled – led down and away. The City of Copenhagen has developed strategies and plans of action over the last decades to accommodate these wet futures; but how can these strategies of rainwater management infrastructures become engaging and transcend mere function?

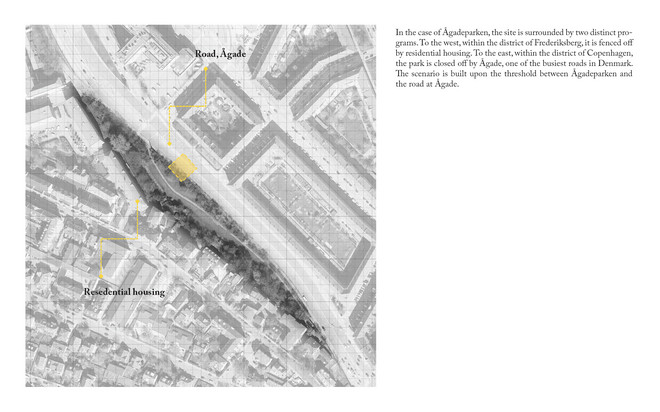

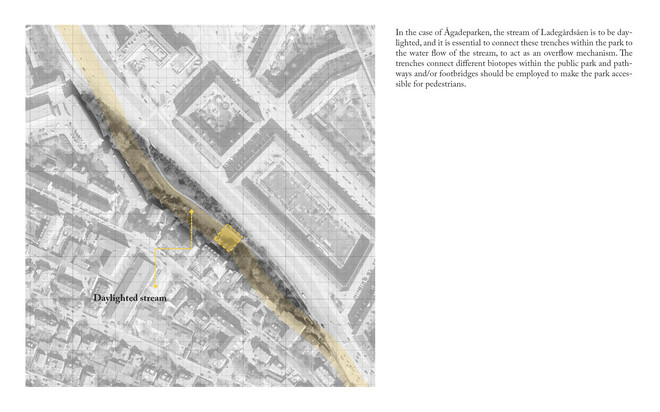

The thesis proposes a strategy in which the trench becomes an active form that acts as a link in a broader infrastructural management network. Five key principles are developed to synthesise and communicate the conducted research. The strategic framework is further demonstrated at Ågadeparken to iterate it within a site-specific context. Three speculative scenarios are developed to contextualise the key principles.

The strategic framework suggests how the trench can bridge contemporary management praxes — but most importantly — bridge the urban water systems and the agencies, human or more-than-human, who reside within the urban environment.

The infrastructures of management

The infrastructures of management

The current infrastructures within the urban environment are categorically designed to conceal the mechanisms and processes that sustain life (2) — depriving dwellers who reside within the cities of opportunities to experience and engage with the flow of urban waters.

This act of concealing is reflected in the root of the word infrastructure itself, as it derives from the Latin prefix infra, meaning ‘below’ and the French word structure which suggests ‘a fixed installation that is needed for something to function’. Spatially it is something that only inhabits the layer below the ground.

The infrastructure of urban water management has, especially after the Cloudburst Management Plan of 2012, become an extra statecraft - a system working without addressing the agency of the entities of the urban environment (7).

Infrastructure as a network of active forms

Infrastructure as a network of active forms

In continuation, Easterling (2016) emphasises the work of sociologist and philosopher Bruno Latour as he argues for infrastructure space being active, as it is composed of both technical and social actors. According to Manual DeLanda (2016), the Actor-network Theory (ANT) by Latour favoured the impact of human actions, neglecting agencies beyond human influence. Through his assemblage theory, DeLanda proposes an emphasis on the temporary nature of interactions to suggest a reciprocal relationship where the assemblage of elements is in constant flux and is constantly being reshaped by its entanglement of elements. In 'The Mushroom at the End of the World' anthropologist Anna L. Tsing (Tsing, 2021) explores these theories of entanglement through the globalised, and commodified, threads of the matsutake mushroom. She builds on Barad’s concept of intra-actions – as the interactions within the network of the matsutake mushroom cannot be understood through a reductionist cause-and-effect relationship. Tsing’s concept of zones of encounter examines how global forces collide with local environments; which responds to what Easterling (2016) defines as the switch. Through an asymmetric approach, Tsing emphasises the role the mushroom plays in shaping economic and social realities. Tsing has situated and employed the assemblage as a lens to examine mutual becomings and intra-actions (Tsing, 2021).

This way of perceiving infrastructures of management as agencies within a wider assemblage is used throughout the thesis to describe and observe the interdependent relationships between infrastructures of management, the city, and residents of the urban environment – and how they constantly co-constitute each other. Active forms treat the organisations of water management as agencies within the urban environment instead of: as collections of objects or volumes (Easterling, 2016 : 44). Active forms assign agency to the spaces that make up infrastructures of water management but also present an opportunity to design spaces of management that are approachable and engaging to the urban ecology. Through this concept, the residents of the urban ecology are part of the spatial process of constituting spaces of management through co-creation and decision-making on a strategic and legislative level.

Another crucial aspect of infrastructure space according to Easterling is the governor who controls the switch and owns the wiring. Historically the municipalities and water supply have been the sole agents in the development of water management infrastructures, working within a closed circuit. The concept of active forms stresses the importance of a co-constitutive process and challenges the hegemonic and political spaces in which strategies and legislation are created. In recent years there has been an increased attention to citizen involvement and co-creation processes to create truly engaging and resilient spaces of management, especially within the region of Copenhagen.

Water as a threat

Water as a threat

Water is constantly moving and morphs between states across local and global networks (Ruby & Ruby, 2017). Precipitation is just one moment of the hydrologic cycle but is deemed a crucial threat to the urban environment when it presents itself as a flood. A higher frequency of heavy rainfall in the temperate zones is expected. As a result, we have rendered precipitation as the moment of reality in an attempt to make the hydrologic cycle manageable (Ruby & Ruby, 2017). This need for control has manifested itself spatially in the way the sewage system is organised. In the moment, a raindrop encounters the paving of a street or runs down the sewage drain it is classified as wastewater. This transformational act of significance is likely due to the cultural and political influence on water management since the 60s.

The view of water as posing a threat has also had implications semantically. The architectural developments and different modus of control have historically influenced our vocabulary when speaking of and about water. Wastewater is water that has presented itself at an inconvenient place, such as in an already flooded street, and as being impure, thereby being of no value or use to us. Stormwater is plain rainwater, but it has the same negative connotations because of its quantity, and because of how it presents itself in the wrong place and time making it difficult to manage. The current sewage system, traditionally planned as piping structured on a grid, contradicts the cyclic nature of water as it short-circuits the hydrologic cycle (Spirn, 1984). The American landscape architect and writer Anne W. Spirn argues the use of what she defines as, nonstructural flood control. Spirn’s nonstructural flood control corresponds with the contemporary concept of nature-based solutions, NBS, in which natural processes, such as infiltration and transpiration, are utilised to manage rainwater.

The cholera epidemic in 1853 had a seminal influence on urban waterways as they were heavily polluted and constituted a health hazard that was solved by culverting the streams. This spatial relationship towards waste entails a need for physical separation and visual concealment to achieve peace of mind (Bille & Sørensen, 2012). In continuation Spirn argues that we need to acknowledge the shortcomings of sewage as; “sewers transport water from one point to another; they do not reduce or eliminate water, they merely change its location” (Spirn, 1984 : 131). The sewage system, and floods controlled through it, are merely a contraption for transportation and detention. Discharging wastewater into the sea does not get rid of it but is just another way of diluting the problem with traditional grey solutions of management.

Trying to understand how urban waters move through and within the urban environment is a means to counter the current hegemonic spatial layout of infrastructures. To be able to meet the needs for flood protection and prevention the infrastructure should be responsive and challenge the static practice of current planning as: “…floods are nothing but water crossing a line that has been drawn in a moment of choice.” (Ruby & Ruby, 2017 : 347). If these projects are planned through lines drawn at one moment in time, they become static and restrictive. When planning rainwater management and climate adaptation, the process needs to account for several scenarios, throughout the year and in different moments of wetness to become truly responsive. Otherwise, they keep countering the hydrologic cycle, reproducing modernist planning practices where the water is treated as a mere commodity.

Infrastructure as landscapes

Infrastructure as landscapes

As our infrastructures of water management have historically been planned with an outset in utilitarianism, and since the introduction of the sewage system, the potential of the above ground has been neglected (10) and radical measures are needed to re-establish the relationship between, what Lund defines as, the ecologies of urbanism and the nature of ecologies (10).

To create truly integrated landscape water management, we need to plan within ecologies and not with typologies (16). Our urban environments need to be able to respond to the changing weather patterns critically and to make urban water systems visible and accessible at different moments within the hydrologic cycle.

The city as a remodelled landscape

The city as a remodelled landscape

Modernist planning is a utilitarian tool employed to structure relationships in the urban environment to achieve certainty and order. The landscapes of urbanism were introduced by Iranian-American architect Mohsen Mostafavi, to challenge the dichotomy of city » « landscape; as landscapes like cities are cultural, social and political agents (Mostafavi & Najle, 2003). He stresses the importance of temporality and relational networks when planning in urban environments as the current planning has constructed “spatial frameworks that serve to reduce diversity of events and to control (and thereby reform) behaviour” (Mostafavi & Najle, 2003). The temporal aspect is for Mostafavi to acknowledge the many circuits of the hydrologic cycle as well as recognise the ever-changing nature of urbanism, as with landscapes, described above by Easterling's definition of multipliers.

Historically urban waters have been managed in the underground networks of the sewage system and connected conduits as detention basins and reservoirs. As aforementioned these infrastructures are designed to conceal (Zalaznik et al., 2023) and draw on our need for separation, leading the hazard down into below-ground spaces and away (Spirn, 1984). Working with infrastructure as landscapes insists on a visible management praxis that utilises the surface and the inherent potential of the local urban ecology present. A landscape-based stormwater management (LSM), as described by Anna A. Lund, operates within five principles of management; detention and transportation, which are principles present in traditional grey solutions, and in addition infiltration, evaporation and cleansing which are present in NBS as they utilise the features of the landscape (Lund, 2018).

These principles are directly influenced by the layout of the ground, as water is in continuous contact with it. This stresses the importance of the surface of our cities, the spatial layout of the ground, and the urban topography, as water always flows towards lower areas. Lund argues that since the introduction of the modern sewage system, the ground has been neglected (Lund, 2018). It also unveils the potential of the ground as it influences the flow and choreography of water. The layout of the ground has the capacity to work with the water flow within all the principles of LSM through spatial manipulation of proportion, sloping, form, and materiality. These spatial manipulations further affect the way the water is visually choreographed as well as matters of humidity, light and materiality are crucial to how the water is perceived (Nikolajew, 2003).

Building upon this notion of the urban environment as landscape, Anna A. Lund (Lund, 2018) argues for the city seen through the lens of a garden. The garden embraces all waters and can work within gradients and different moments of wetness (Ruby & Ruby, 2017). It respects other moments of the hydrological cycle than just precipitation. According to Lund (Lund, 2018 : 113) the city is a remodelled landscape and constructs an ecology of urbanism that acknowledges a network of agencies; agents, resources, skills, technology, power, values, and memory. Following Mostafi and Spirn, Lund further develops a model to arrange the city and landscape as form that exist within urbanism and nature as ecologies. This model embraces the temporal and ecological aspects of urbanism that Mostafi requested and enables a responsive approach to engage with urbanism and infrastructures as landscapes.

The idea of the planetary garden and the gardener

The idea of the planetary garden and the gardener

The work of Anna A. Lund and her concept of the garden as a model draws from the practice and framework of French landscape architect and gardener Gille Clément. The garden is historically referred to as an enclosure that protects the best, as in paradise. Clément develops upon this historical notion to promote a discourse where the garden represents a territory without borders as it is a landscape of commons that works within the rules of the environment, “but as it contains a dream; it also carries a societal project” (Clément et al., 2020 : 26). In this thesis his notion and differentiation between nature, environment, landscape, and the garden are employed to build upon this discourse and serve yet another theoretical perspective, as with the concept of active forms by Easterling, to approach infrastructures as a responsive network.

The environment is the scientific interpretation of our surroundings whereas, in contrast, the landscape is an experienced space. For Clément, the landscape is scenic and experienced through our eyes but is not limited to any scale or materiality. The garden and nature in general, are composed by these landscapes but can only truly be experienced through the act of gardening (Clément et al., 2020 : 21-22). Gardening is for Clément more than just keeping: a few beautiful rose bushes in bloom to uphold the image of a garden (Zarzycki, 2021). Gardening is a never-ending act of guarding the landscape by doing the most for and the minimum against. It is an attention to the landscape and garden as in motion, in which continuous reciprocal maintenance is needed to ensure the existence of the garden – and in extension the gardener.

According to Clément the garden is planetary as it exists and is submerged within nature. This idea of the planetary garden promotes consideration of the ecological network it exists within and the gardener – a term Clément uses to refer to promote the works of landscape architects and planners – which work within its spaces. As humans, we all occupy and inhabit the same spaces, the garden proposes a way of working with and within the natural ecologies; which is ever relevant to the urban ecologies as well (Zarzycki, 2021). “Birds, ants and mushrooms recognise no boundaries between territory that is policed and space that is wild” says Clément to stress the importance of ecological attention to and broadened perception of the garden.

In a garden, all waters have a purpose and are not restricted by our sociocultural concepts or classifications. Throughout history, this domain has been influenced by the cartesian dichotomy of nature »« culture to fit within modernist ideals. The garden has been viewed and treated as culture by architects and planners, as seen in the gardens of the Baroque and the Renaissance in Europe, in which nature is made controllable through confined layouts and geometrical principles of order rooted in the Vitruvian writings of especially Leon Battista Alberti. In these gardens, the garden itself is a museum of nature, as the historical development of water management infrastructures, reflects a use of architecture to create cultural symbols of status and wealth. The existence of the garden is threatened, and Clément advocates for a view of the garden as in motion. You can plan and construct a garden, but this reductionist approach leaves out the gardener. As presented above Clément argues that the garden is needed for the gardener to exist, but the gardener is crucial, especially in urban environments, as planners and landscape architects tend to only regulate within systemic frameworks. But a garden is never done. The gardener “interprets the inventions of life” and is needed to maintain and care for urban garden spaces (Clément et al., 2020 : 20). In this thesis the notion of the gardener serves to stress the importance of maintenance of the urban waterscapes through an attention to the importance of public caretakers.

Layers of landscapes

Layers of landscapes

“It matters what matters we use

to think other matters with;

it matters what stories we tell

to tell other stories with;

it matters what knots knot knots,

...

It matters what worlds make worlds,

what worlds make stories”

(Haraway, 2016 : 12)

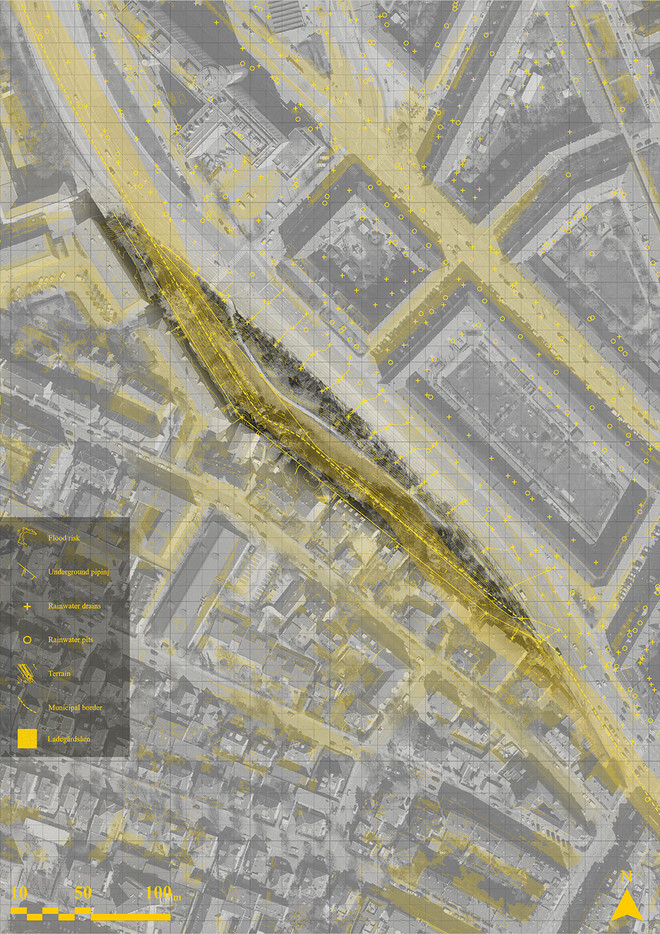

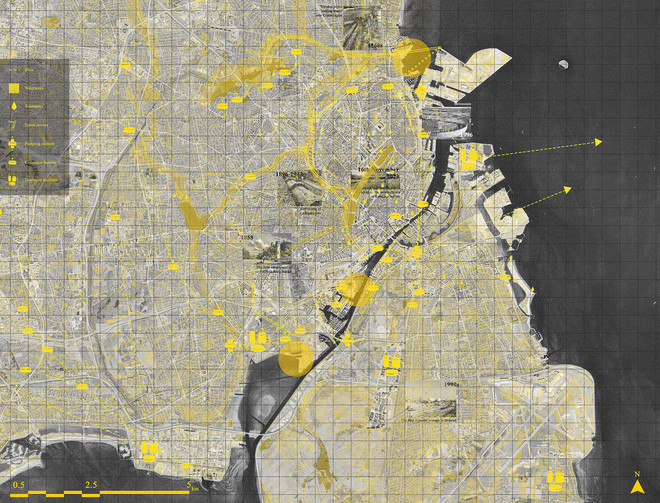

A new cartography is needed to contain both living matters across the layers of the ground and the relationships between agencies of the urban ecology. In The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique and Invention, James Corner proposes a mapping practice through the figures of Deleuze and Guattari. The idea of rhizomatic mappings or thickened maps enables a creative potential within the medium of cartography. The map becomes a strategic and imaginative tool to investigate and uncover new realities. By employing open-ended connections and an emphasis on the relationships between various agencies it transcends mere representation, by acknowledging their agency in shaping the urban conditions (Corner, 1999).

Corner introduces the concepts of finding and founding which resemble the epistemologies of design research, design about, for and through design, as introduced by German design theoretician Wolfgang Jonas. Finding refers to the act of revealing realities previously hidden in seemingly exhausted ground, where founding is concerned with the creation of something from these discoveries: “Mapping is neither secondary nor representational but doubly operative: digging, finding and exposing on the one hand, and relating, connecting and structuring on the other.” (Corner 1999 : 93). It is a mapping that insists on remaking territory through the act of attention to relationships rather than reproducing, by tracing and recording, existing knowledge. The thick in the concept of thickened maps refers to the layering of these findings which creates new realities to constitute future foundings.

Lebanese and Algerian architects Ghosn and Jazairy address the same potential, as it: ”is a device that brings the Earth into matters of concern; it makes visible absent things…” (Ghosn and Jazairy 2018 : 22). The concept of finding and founding are further developed and presented as methods in Terra Forma by Aït-Touati, Arénes and Grégoire, in which they investigate possible ways of exploring the unknown world with “a new cartography of living things rather than space available for conquest or colonization” (Aït-Touati et al. 2022 : back cover copy). Through a mapping concerned with the thickness of the ground and the entanglement of agencies, they speculate in ways of visualising and constituting unknown realities within a known world, our own. A discourse where data and mapping are, as infrastructures, treated as living landscapes (Aït-Touati et al., 2022). This method of mapping through finding and founding is employed throughout this thesis but especially through the case studies and the following design-oriented research to unfold the potential that lies in reimagining Ågadeparken.

Pure, in the right place, and at the right time, water is an essential resource:

impure, and in the wrong place and time,

water is a life-threatening hazard.

— Anne W. Spirn, The Granite Garden (1984 : 142)

Case studies

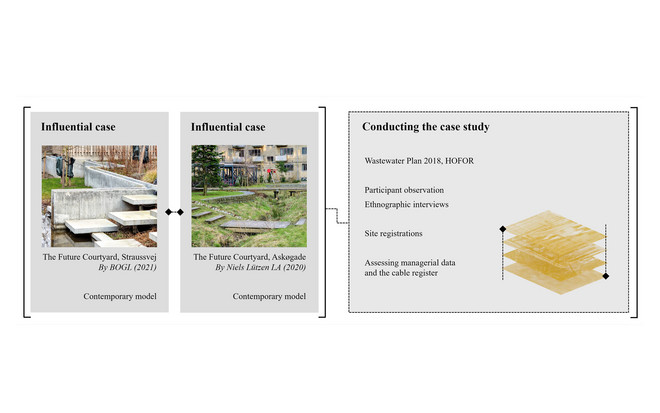

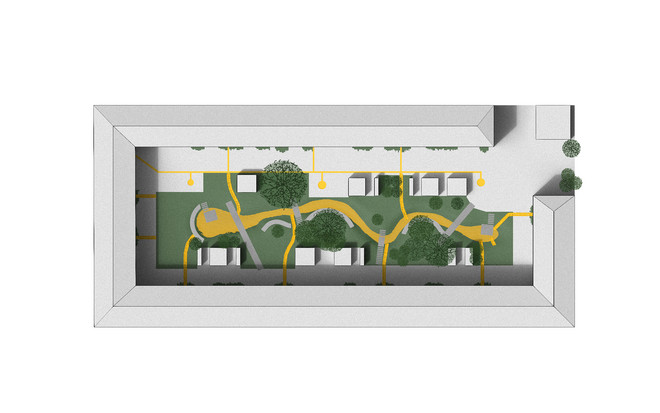

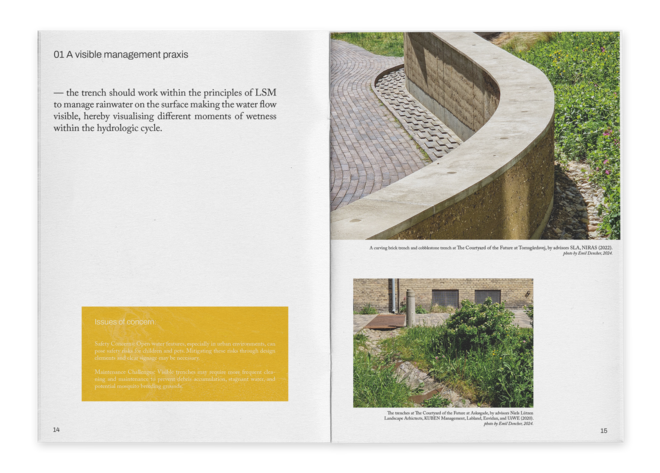

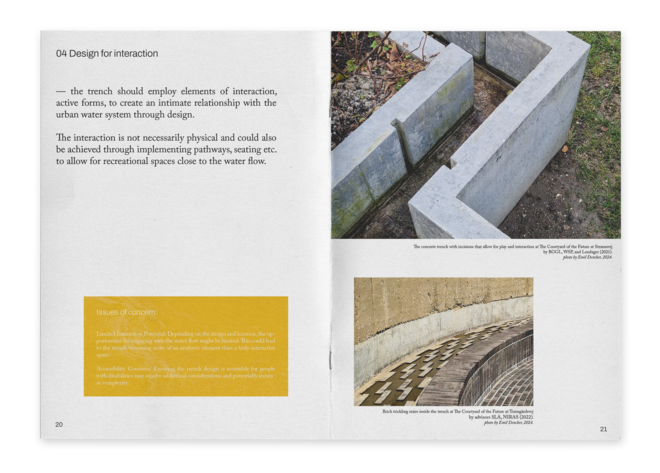

The Courtyard of the Future at Straussvej, 2021 is a collaboration between The City of Copenhagen, HOFOR and the residents. The architectural office BOGL was the main advisor on the project, in partnership with the consulting engineers WSP and material reuse specialists at Lendager Group.

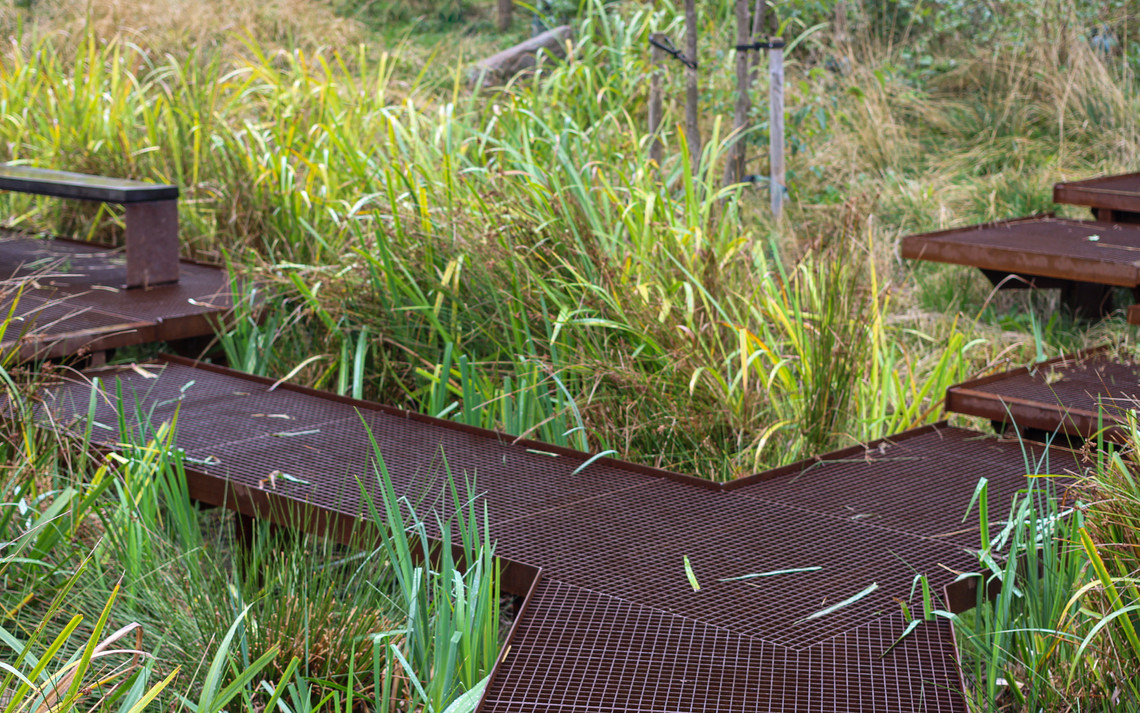

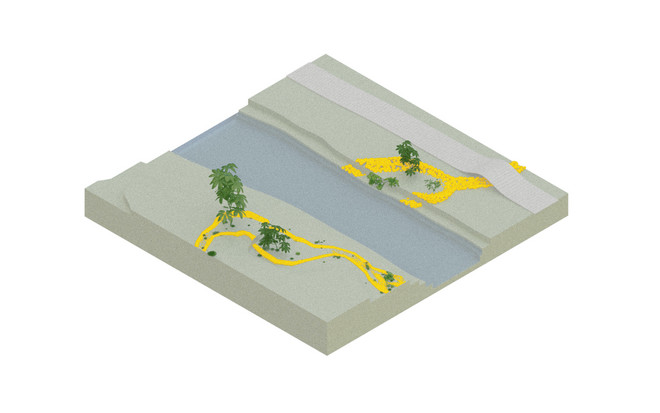

KEY FINDINGS: A resilient climate adaptation in which the trench becomes the main feature of rainwater management as well as creating flowscapes of different engagements. The trench also acts as a climate barrier making the entirety of the courtyard a detention pool for management of significant volumes of water. The elevated design of the trench makes it accessible and educational for residents and children to learn about and interact with the water cycle.

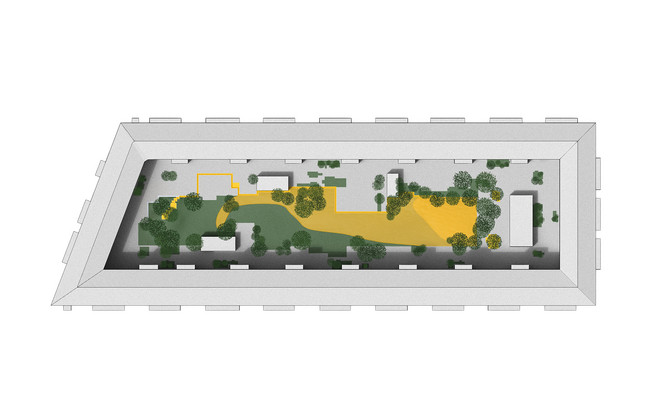

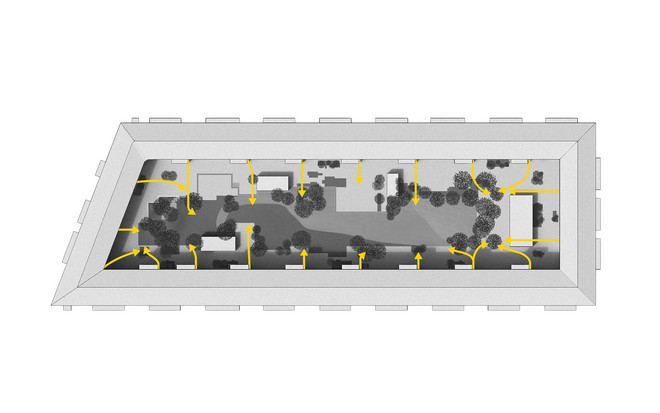

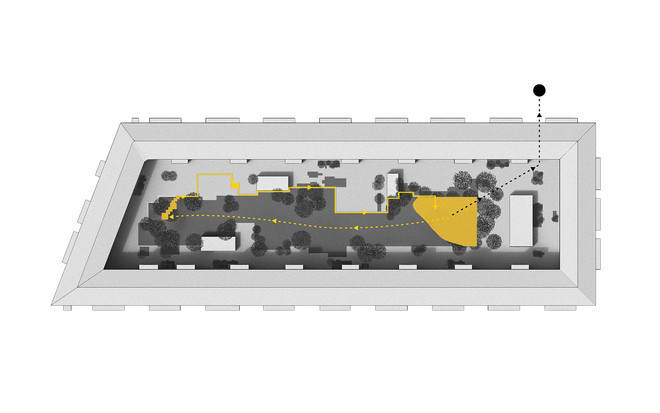

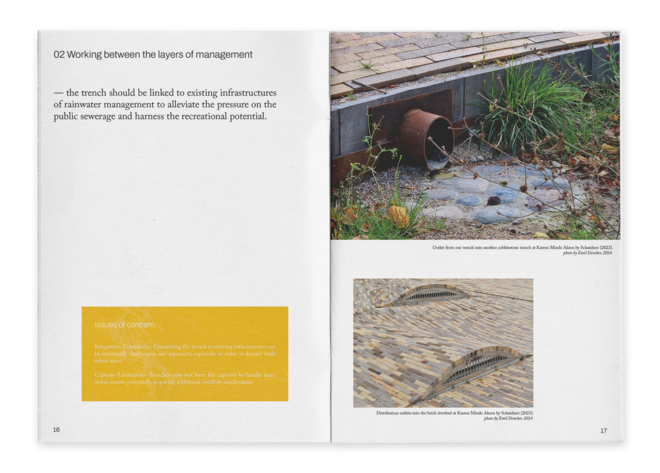

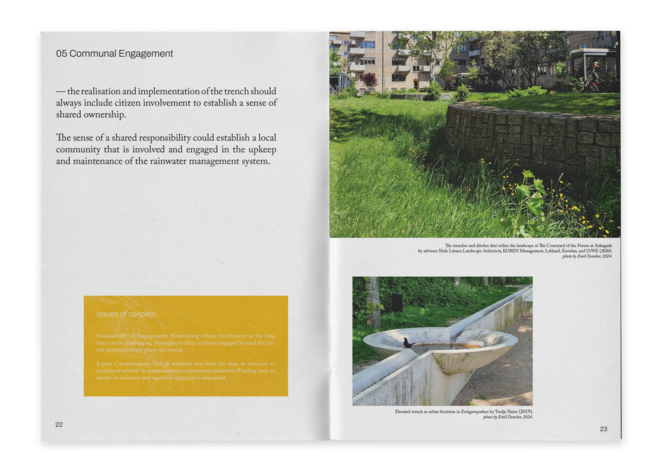

The Courtyard of the Future at Askøgade, 2020 is as with the previous case developed in a collaboration between The City of Copenhagen, HOFOR and the residents of the area. The architectural offices Niels Lützen and LABLAND were the main advisors on the project, in partnership with Kuben Management and consulting agencies Envidan and Urgent Agency.

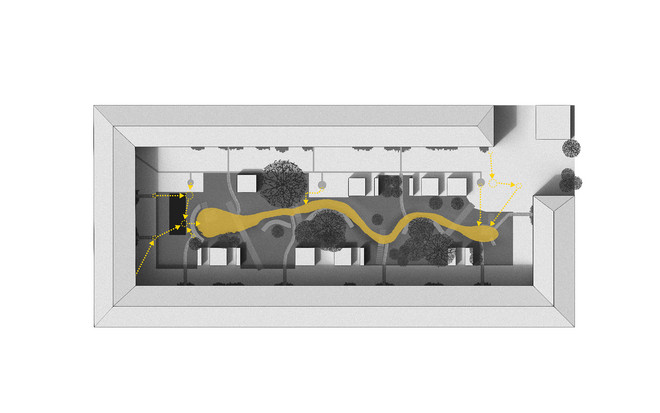

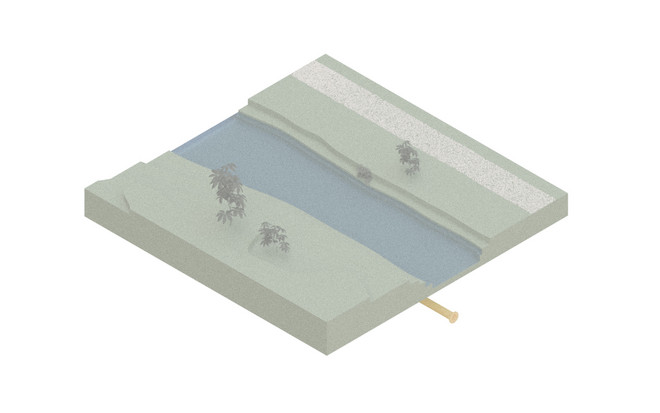

KEY FINDINGS: A project that demonstrated how different spatialities and materialities of the trench can be choreographed to seamlessly delegate the rainwater through an inwards motion. The meandering ditch in the centre of the courtyard creates a temporal space in times of precipitation as the water is led there to infiltrate, creating a temporary creek. Hilltops, bridges, and pathways make the area accessible in all weather and establish a space in which the water adds to the recreational value.

The two cases from the project 'The Courtyard of the Future', which was part of 'The Climate Resilient Neighbourhood Østerbro' were chosen as influential cases, as they have had an impact on the current discourse of utilising nature-based solutions and landscape-based stormwater management as integral elements of rainwater management.

Strategic Framework

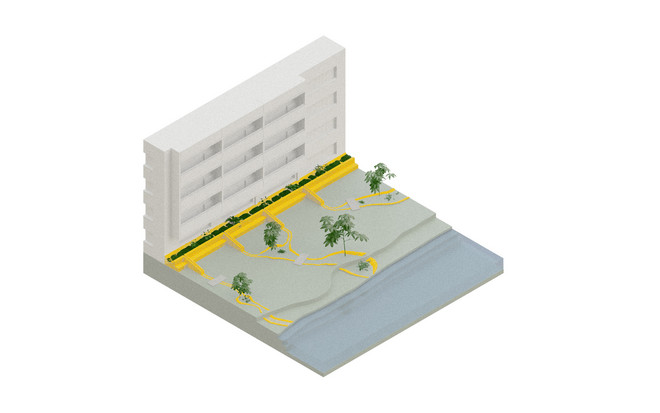

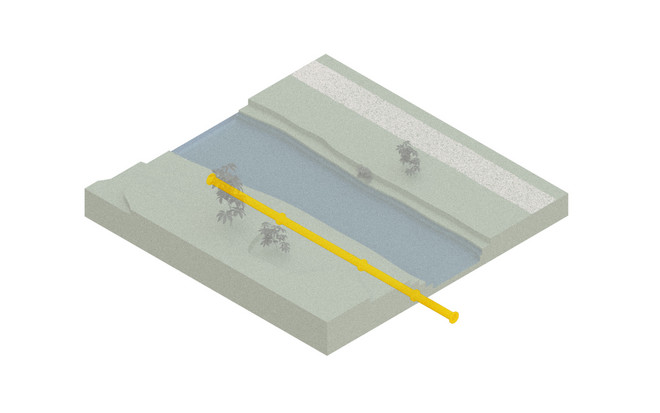

The strategic framework synthesises the strategy into five key principles. The five key principles act as guidelines for how the trench can be reactualised as a link in rainwater management, that fosters visible and accessible urban flowscapes for the agencies within the urban environment.

Access the strategic framework catalogue HERE.

or download it from the profile header ↑

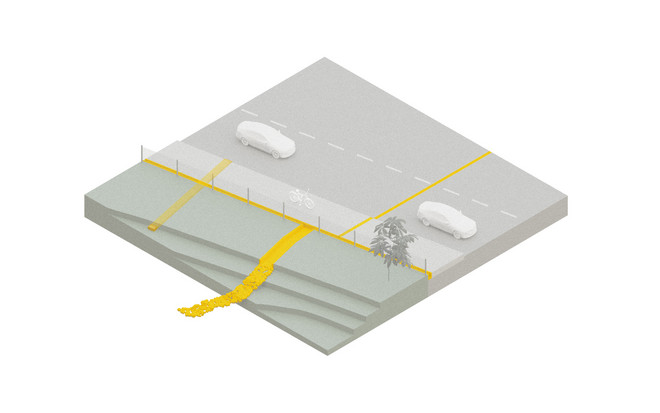

1. A VISIBLE MANAGEMENT PRAXIS

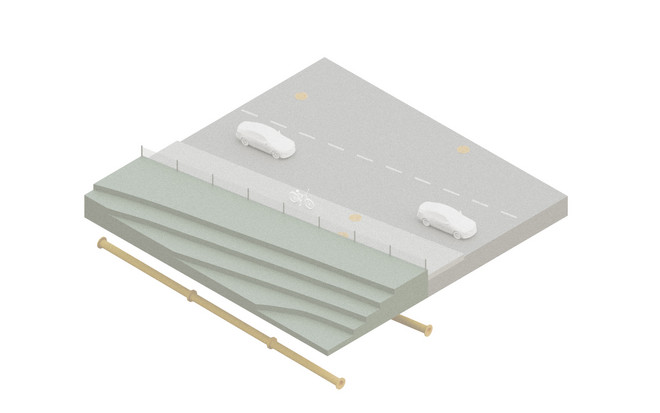

— the trench should work within the principles of LSM to manage rainwater on the surface making the water flow visible, hereby visualising different moments of wetness within the hydrologic cycle.

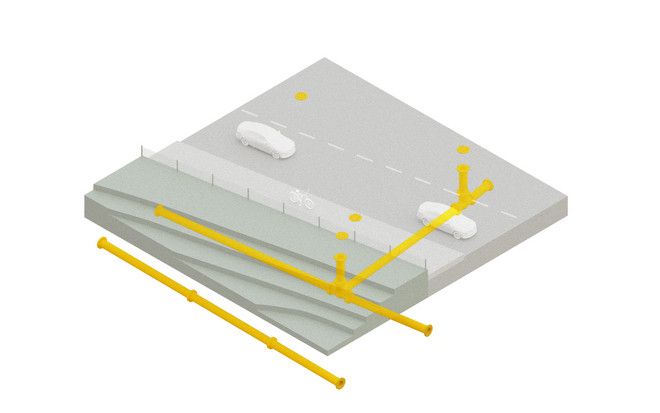

2. WORKING BETWEEN THE LAYERS OF MANAGEMENT

— the trench should be linked to existing infrastructures of rainwater management to alleviate the pressure on the public sewerage and harness the recreational potential.

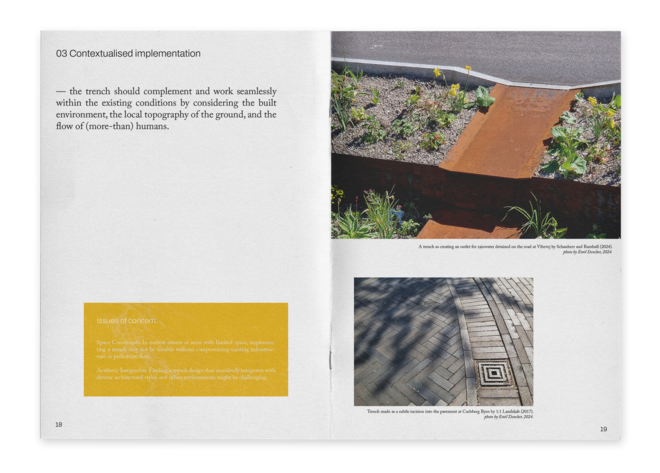

3. CONTEXTUAL IMPLEMENTATION

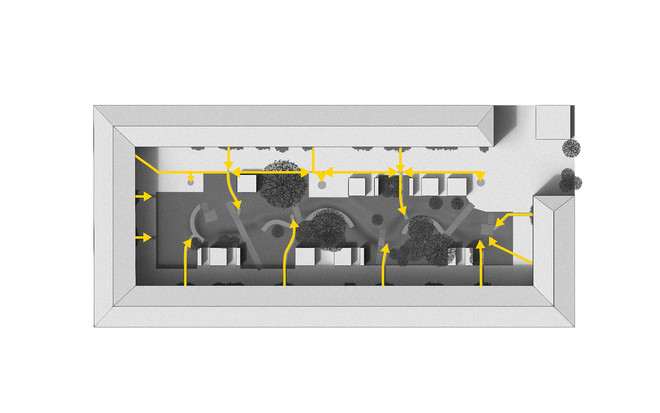

— the trench should complement and work seamlessly within the existing conditions by considering the built environment, the local topography, and the flow of (more-than) humans.

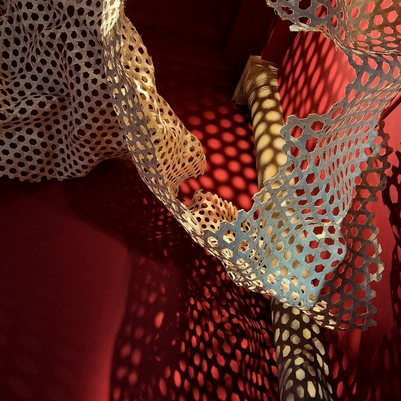

4. DESIGN FOR INTERACTION

— the trench should employ elements of interaction, active forms, to create an intimate relationship with the urban water system through design. The interaction is not necessarily physical and could also be achieved through implementing pathways, seating etc. to allow for recreational spaces close to the water flow.

5. COMMUNAL ENGAGEMENT

— the realisation and implementation of the trench should always include citizen involvement to establish a sense of shared ownership. The sense of a shared responsibility could establish a local community that is involved and engaged in the maintenance of the rainwater management system.

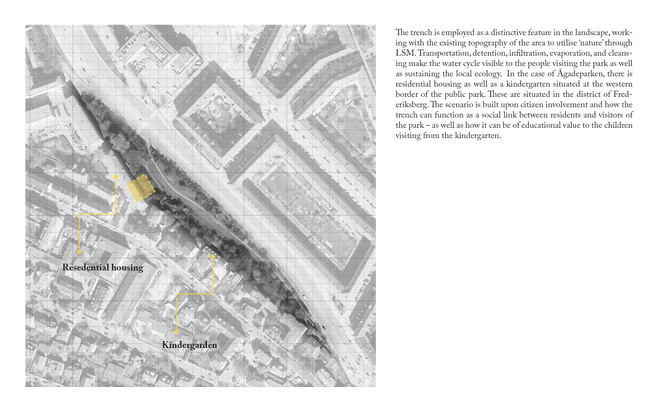

Speculative scenarios

The speculative scenarios are developed through narratives to anchor them within the strategic framework to help demonstrate the key principles and the developed strategy in a site-specific context. The scenarios are developed through a speculative lens, to imagine and demonstrate how the trench can act as a link in rainwater management, presenting different forms of engagement by employing the trench as an active form. The speculative scenarios further suggest how Ågadeparken, a site currently investigated in terms of its rainwater management potential, can be reimagined regarding future climate adaptation.

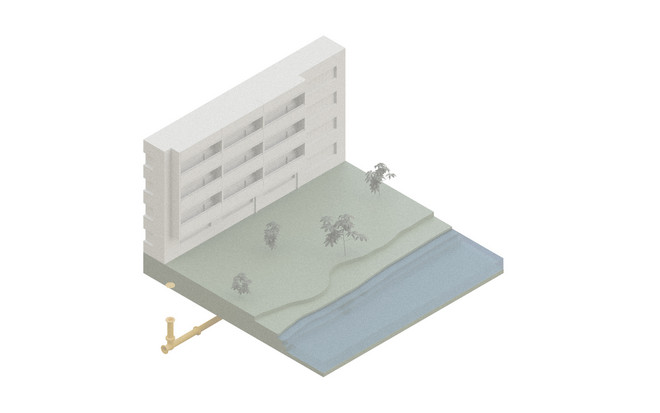

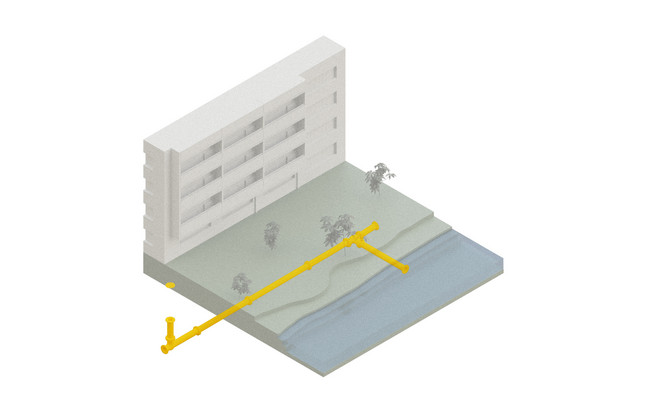

The first scenario is situated on the threshold between the public park and the surrounding urban environment. The second scenario is situated on the opposite side of the park adjacent to the residential housing. The third scenario is developed as an extension of the second scenario as it choreographs the trenches from being a social and cultural link to a link between biotopes.

References and further reading

References and further reading

(1) Aït-Touati, F., Arènes, A., Grégoire, A., & Latour, B. (2022).

Terra forma: A book of speculative maps. The MIT Press.

(2) Batlle, E., & Roig, J. (2022).

Merging city & nature: 10 commitments to combat climate change. Actar Publishers.

(3) Bille, M., & Sørensen, T. F. (2012).

Materialitet: En indføring i kultur, identitet og teknologi.

(4) Clément, G., Finn, M., Lund, A. A., Parsons, L., & Van Melle, E. (2020).

Gardens, landscape and nature’s genius. Ikaros Press.

(5) Corner, J. (1999). The Agency of Mapping: Speculation, Critique and Invention. In Mappings (pp. 213–252). University of Chicago Press.

(6) DeLanda, M. (2016).

Assemblage theory. Edinburgh University Press.

(7) Easterling, K. (2016).

Extrastatecraft: The power of infrastructure space. Verso.

(8) Ghosn, R., & Jazairy, E. H. (2018).

Geostories: Another architecture for the environment. Actar.

(9) Haraway, D. (2016).

Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press.

(10) Lund, A. A. (2018).

Room for rain: The city as a garden and the future of streets. Københavns Universitet. Det Natur- og Biovidenskabelige Fakultet. Institut for Geovidenskab og Naturforvaltning. Landskabsarkitektur og Planlægning.

(11) Mostafavi, M., & Najle, C. (2003).

Landscape urbanism: A manuel for the machinic landscape. Architectural association.

(12) Nikolajew, M. (2003).

At læse vandet: Et redskab til analyse af vandkunst og fontæner. Kunstakademiets Arkitektskole.

(13) Ruby, A., & Ruby, I. (2017). Infrastructure Space: Including a visual Atlas. Ruby Press.

(14) Spirn, A. W. (1984).

The Granite Garden: Urban Nature And Human Design. Basic Books.

(15) Tsing, A. L. (2021).

The mushroom at the end of the world: On the possibility of life in capitalist ruins. Princeton University Press.

(16) Zalaznik, A. M., Brodnik, U., & Pugelj, A. (2023).

Nature-based Solutions for Integrated Local Water Management. Kemija u Industriji, 9–10. https://doi.org/10.15255/KUI.2022.062

(16) Zarzycki, L. (2021, February 16).

In practice: Gilles Clément on the planetary garden. Architectural Review. https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/in-practice/in-practice-gil…

Det Kongelige Akademi understøtter FN’s verdensmål

Siden 2017 har Det Kongelige Akademi arbejdet med FN’s verdensmål. Det afspejler sig i forskning, undervisning og afgangsprojekter. Dette projekt har forholdt sig til følgende FN-mål