Constructing Hegemony

Twenty-five years after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, or Belfast Agreement, Loyalist paramilitary groups pursue to keep alive a lethal narrative and purpose concerning the sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland.

From the territory of political architecture, this project engages speculatively with spatial and programatic strategies that could subvert against components of hegemonic structures like sectarianism and it will challenge some of the ideological and procedural principles on which the Northern Irish conflict is based.

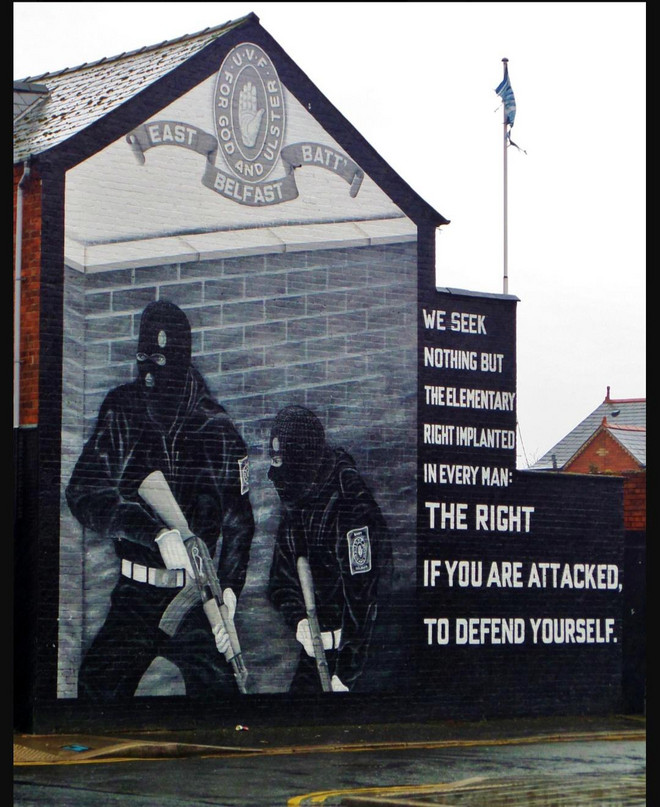

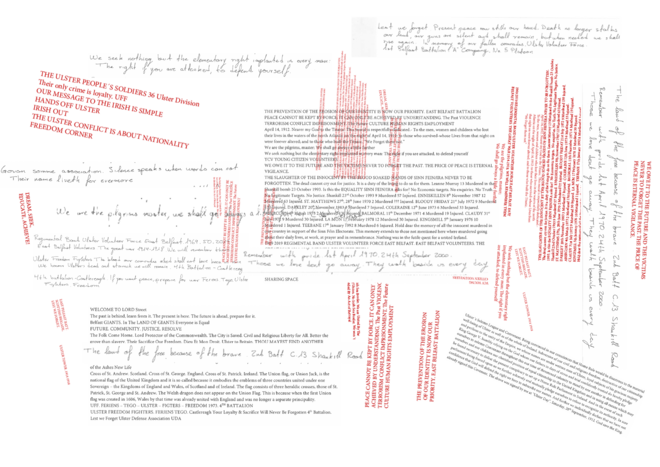

Political murals are one of many territorial strategies by which these violent organizations appropriate public space in segregated neighbourhoods, using semiotics as a tool of power display that treath a long peace process and negatively impact the social, economic, and every-day life over time.

[[{"fid":"369643","view_mode":"top","fields":{"format":"top","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":""},"type":"media","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-top"}}]]

The Northern Irish conflict is rooted in deep-seated political, economic, and religious divisions between two main communities, which have long been at odds over the status of Northern Ireland as part of the United Kingdom. These divisions are the result of religious wars that are centuries old in which the Catholic and Protestant traditions have repeatedly clashed since the seventeenth century.

Apart from the British State, paramilitary organizations have been major actors in the conflict. Loyalist paramilitaries, such as the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), used violence to resist Irish nationalism and to maintain the Union with Britain. On the other hand, Republican paramilitaries, such as the Irish Republican Army (IRA), used violence to pursue their goal of a united Ireland.

The paramilitary groups were responsible for many of the attacks during the Troubles, these attacks were characterized by bombings, assassinations, and street violence, with both sides committing acts of terrorism. The UVF were responsible for over five hundred deaths throughout the troubles. Since the de-escalation of violent confrontations, paramilitary groups have shifted their activities from bombings and killings into more invisible practices of controlling territories.

Today, loyalist and republican terrorist groups are still in existence, unwilling to transition to a peaceful negotiation of the conflict.

Furthermore, they portray the narrative of being prepared for any violence that could arise because of political decisions. The contemporary UVF has transitioned into a criminal organization based on a capitalistic business model responsible for the drug market of vast areas of Northern Ireland. They are also involved in multiple cases of money laundering, racketeering, extortion, and smuggling.

Political murals are one of many territorial strategies by which these violent organizations appropriate public space in segregated neighbourhoods, using semiotics as a tool of power display that treath a long peace process and negatively impact the social, economic, and every-day life over time.

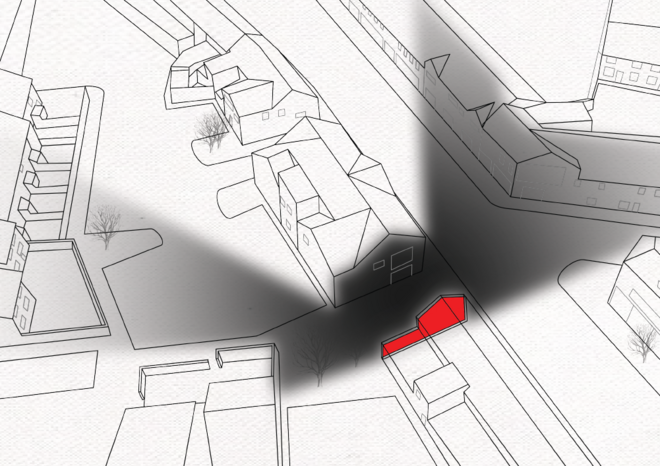

A very striking illusion is experienced when passing by this mural located on Castlereagh Road, when, the gunmen’s steely gaze seems to track the viewers and the aim of the rifle always points to whoever dares to look as one walks past the wall. What happens in front of it is an experience that affects the intellectual level of individuals and affects the communal behaviour of the vicinity.

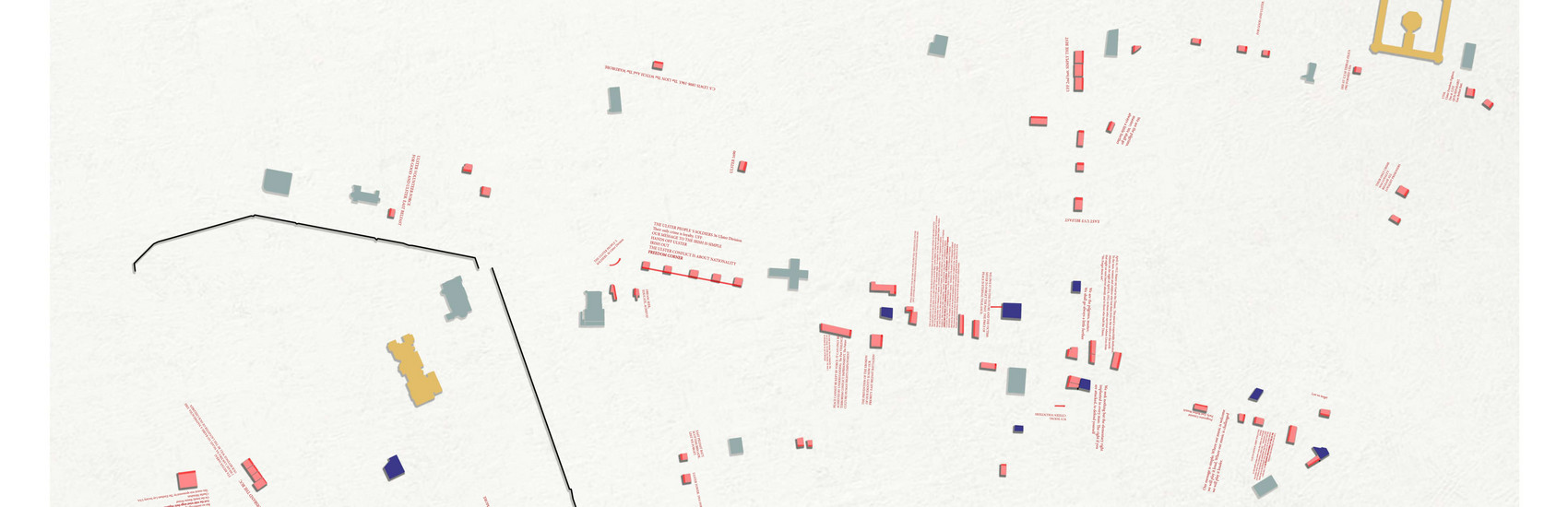

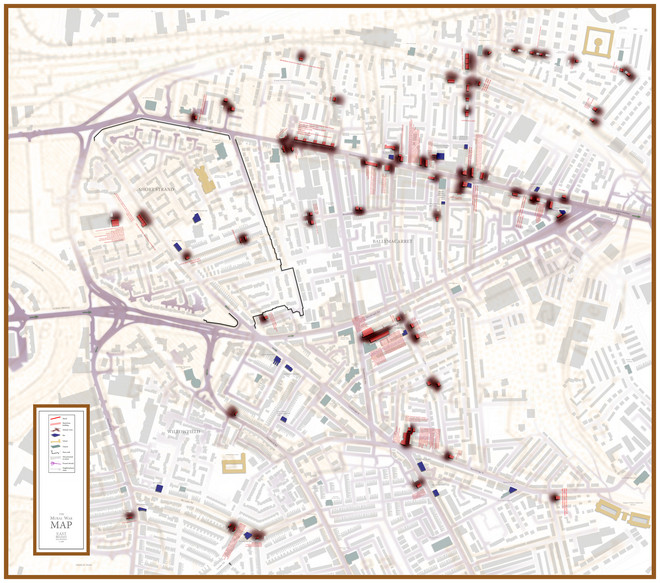

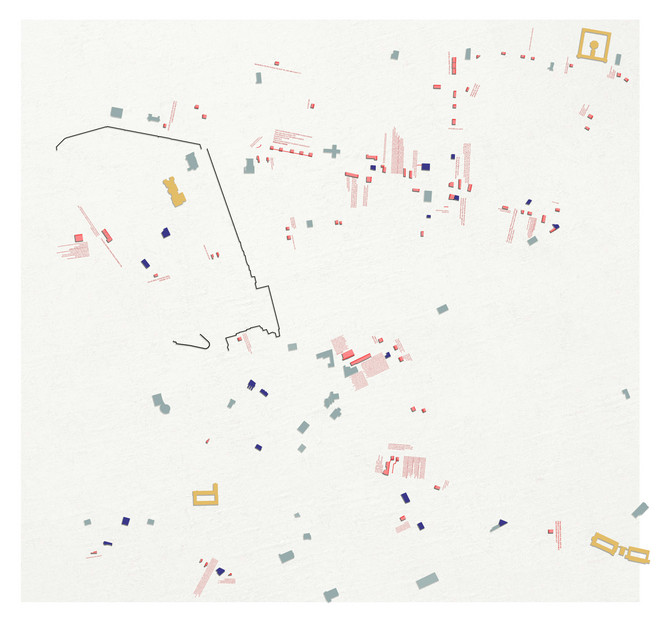

Those semiotic areas of distress and its relation to other strategic tokens of territorialization compose this mural map of east Belfast. It is also called The mural war map as if the distress from the murals were wounds in the territory, affecting the every day life of the people.

Suddenly one can see this vast amount of more than 600 murals in the whole city as what philosopher Manuel DeLanda calls an Assemblage, which is a complex system composed of a variety of interconnected entities that are constantly interacting and evolving. DeLanda argues that assemblages are characterized by their capacity for self-organization and emergence, meaning that they can create new forms and behaviours that are not reducible to the properties of their individual parts.

Assemblages are not just static structures but are dynamic and always in flux, with their constituent parts interacting and changing over time. the matter of time adds yet a new layer of complexity that suggest considering murals as temporal tokens or “semiotic bombs” in a conflicting territory.

By deconstructing the concept of hegemony and relating its situated example in East Belfast, this thesis project also analizes the paramilitary hegemony and its relation to the everyday reproduction of habits that reinforce a narrative of segregation.

The paramilitary groups’ control over East Belfast involves a complex power dynamic, which can be understood by studying the concept of hegemony. According to Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci, hegemony refers to the cultural, ideological, and moral leadership of a dominant group over subordinate groups, in which the dominant group’s values, beliefs, and interests become the common sense of society.

Using Antonio Gramsci´s idea of Hegemony, I claim that: loyalist groups in East Belfast claim cultural, ideological and moral leadership over what would be called subordinate groups, in this case a segregated, hurt society that is tired of the political conflict, but that, by only living their lives and participating in that society, they reinforce the dominance of the ruling class, and their group's values, beliefs, and interests become the common sense of society.

It involves the creation and dissemination of ideas and values that make the existing power structure seem natural and inevitable. As a result, they are less likely to challenge the status quo and more likely to comply with the dominant group’s wishes.

But, to what degree architecture plays a role in its preservation? According to what one can see and sense on the gables of houses in troubled neighbourhoods like The Shankill, Falls or East Belfast, the Troubles are very alive, there is a permanent state of alertness and preparedness for confrontation.

What I claim is that Architecture and art can play an instrumental role in maintaining hegemony. This is by shaping the built environment and creating symbolic representations of power and control murals, flags, walls, painted street kerbs, and memorials. These are what I call Tokens of Territorialization. This is because - ultimately - these manifestations are about territory, about controlling it and displaying that control.

I chose to investigate the repetition of habits and socializing in relation to the construction to hegemonic narratives.

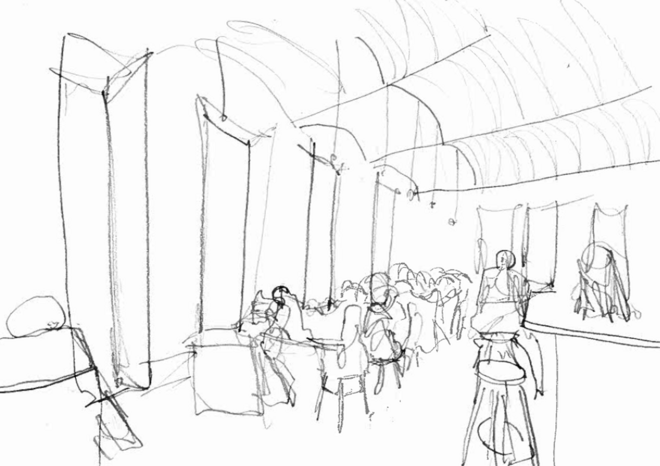

Britain has a big tradition of gathering every week in Pubs, just as a practice of socialization, not necessarily related to alcohol consumption per se, but really as a habit of with our friends in a pub, simply by living our lives the way we live them we reproduce habits that construct hegemony day by day.

It is in the domesticity where we as social beings construct our common sense and reinforce hegemonic values, ideologies, and more pragmatically, negotiate our contribution to the construction of this common sense.

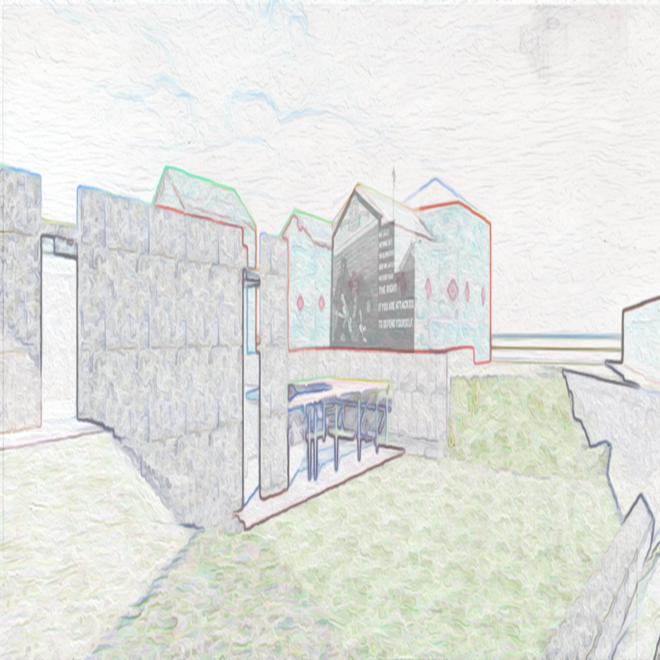

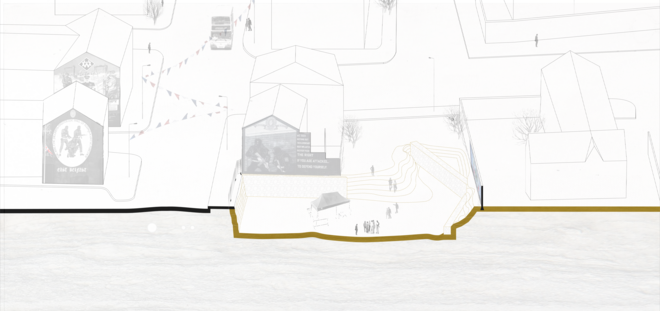

This a particular area in East Belfast, where multiple murals affect a semiotic area surrounding an abandoned plot that is used as a car park. is a particular dense area in terms of violent expressions of the lethal hegemony because it has lots of aggressive murals, flags and other tokens. I will situate this on the big map.

A Public House offers the community of East Belfast place for socializing around traditional and non-traditional practices as a subversive token against paramilitary Hegemony.

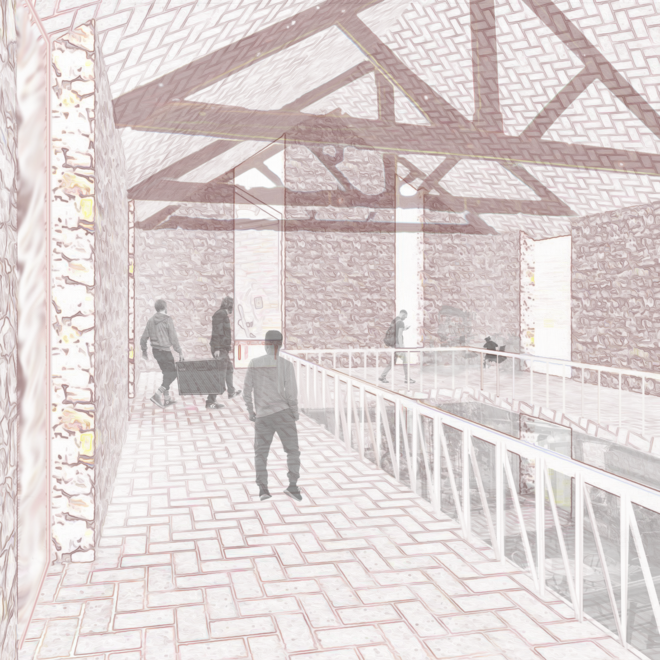

The building is flexible enough to allow multiple happenings in the inside of a building and inside of a public garden that doesn’t close and its managed by a new kind of institution formed by civil society, the leadership of a charity institution called EAST BELFAST PARNERSHIP currently located one block away from the site

Now It is a whole in the ground, with still a relation to the murals, but a different one.

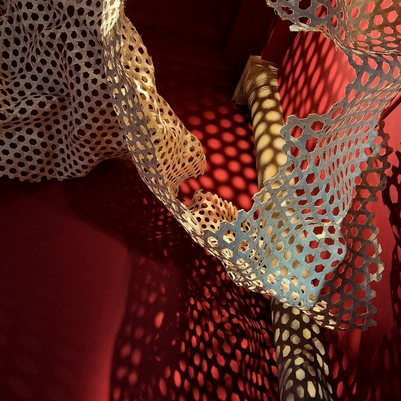

The fact of being underground is a gesture of detachment from the everyday life of the street level, from the quotidianity of the harsh and poor public places in the surroundings.

The underground Patio is in close contact with an UVF mural. I chose to confront it in a very direct way, that allows to look at it in a very different way, from a place of color and tranquility, in direct conflict with the almost ridiculous depiction of men with guns. Pointing not to the ground now, but to their own foundations. The mural stops at street level, and from there towards the bottom, the underground, the rocks, the plants, a reflecting pool disturbs the message, makes a glitch in the perception of the semiotics. Breaks the contact of the mural with its foundation and the contact to the ground.

Such a re-neighbouring practice could serve as a space for contestation against the hegemonic structures of sectarianism in Belfast, by promoting alternative forms of territorialization based on consent rather than coercion. By creating spaces that encourage cross-community engagement and interaction, it could help break down the barriers that have historically kept communities separated and facilitate the formation of new, less segregated neighbourhood of East Belfast.

A PUBLIC HOUSE IN BELFAST

… that frames the possibility of a different setting for socializing around

traditional practices like the ones in a Pub, a tavern in the night, a coffeeshop

during the day, and also not-so-traditional practices like workshops, communal

activities like gardening, dance sessions, and possibilities for engagement

of the community in a non-sectarian place, non pre-defined space.

Det Kongelige Akademi understøtter FN’s verdensmål

Siden 2017 har Det Kongelige Akademi arbejdet med FN’s verdensmål. Det afspejler sig i forskning, undervisning og afgangsprojekter. Dette projekt har forholdt sig til følgende FN-mål