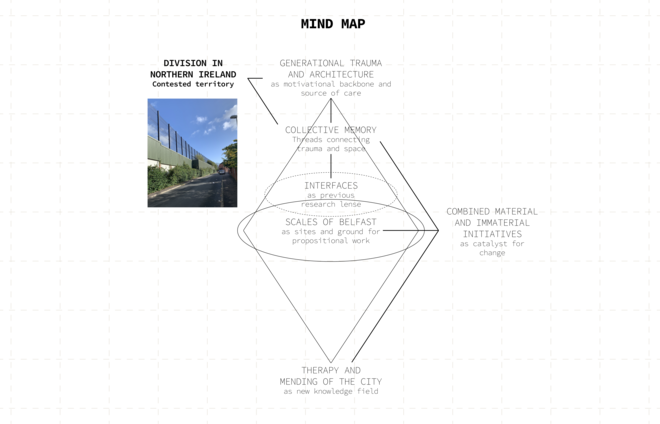

Mending Architecture: Care as a practice and catalyst for intergenerational change

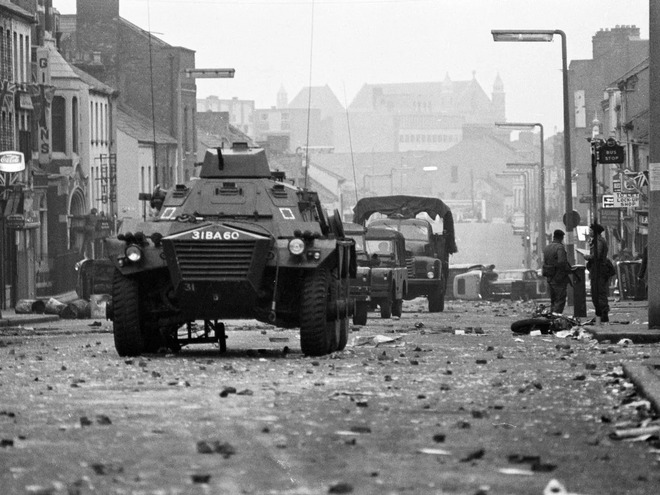

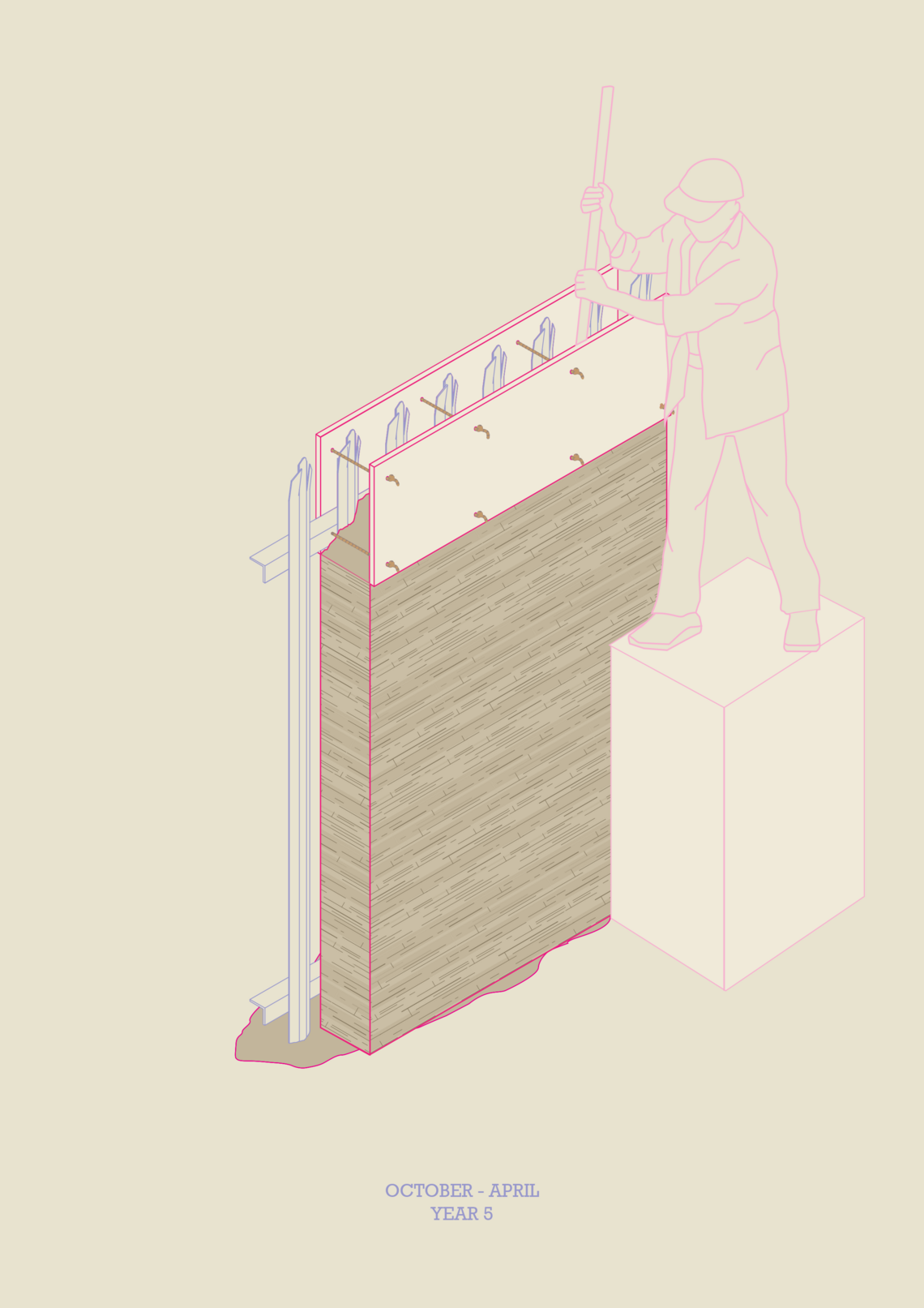

In Belfast, communities have been living separately, divided by walls, identity, memory. The project weaves-in an ecosystem of initiatives requiring care and maintenance with the current entanglement of spaces in the neighborhoods of Falls and Shankill. Catalysts have been designed to change perceptions of spaces of conflict, where memory of violence and division render possibility for change unperceivable.

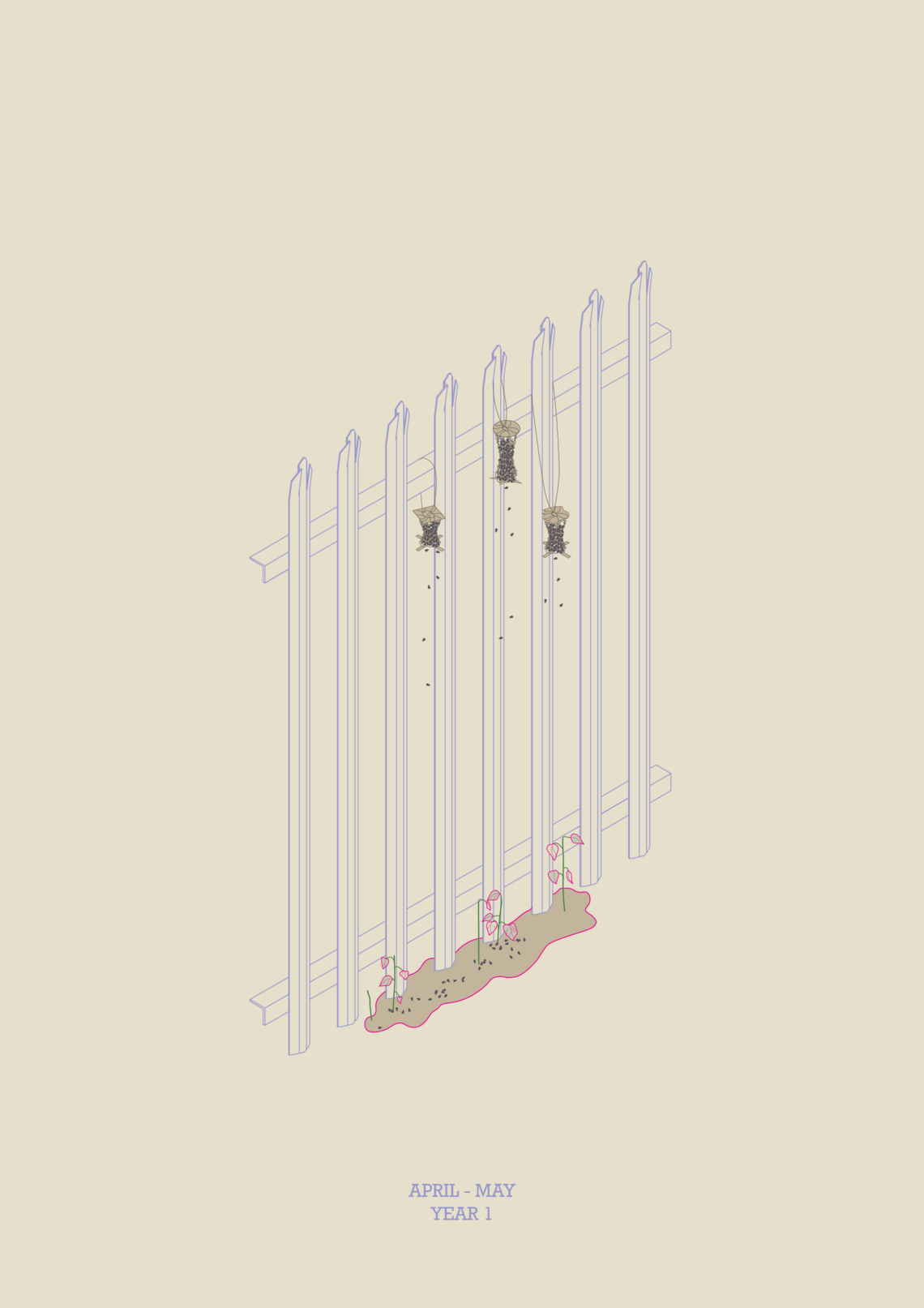

Catalyst #1: The bird+soil feeder initiative

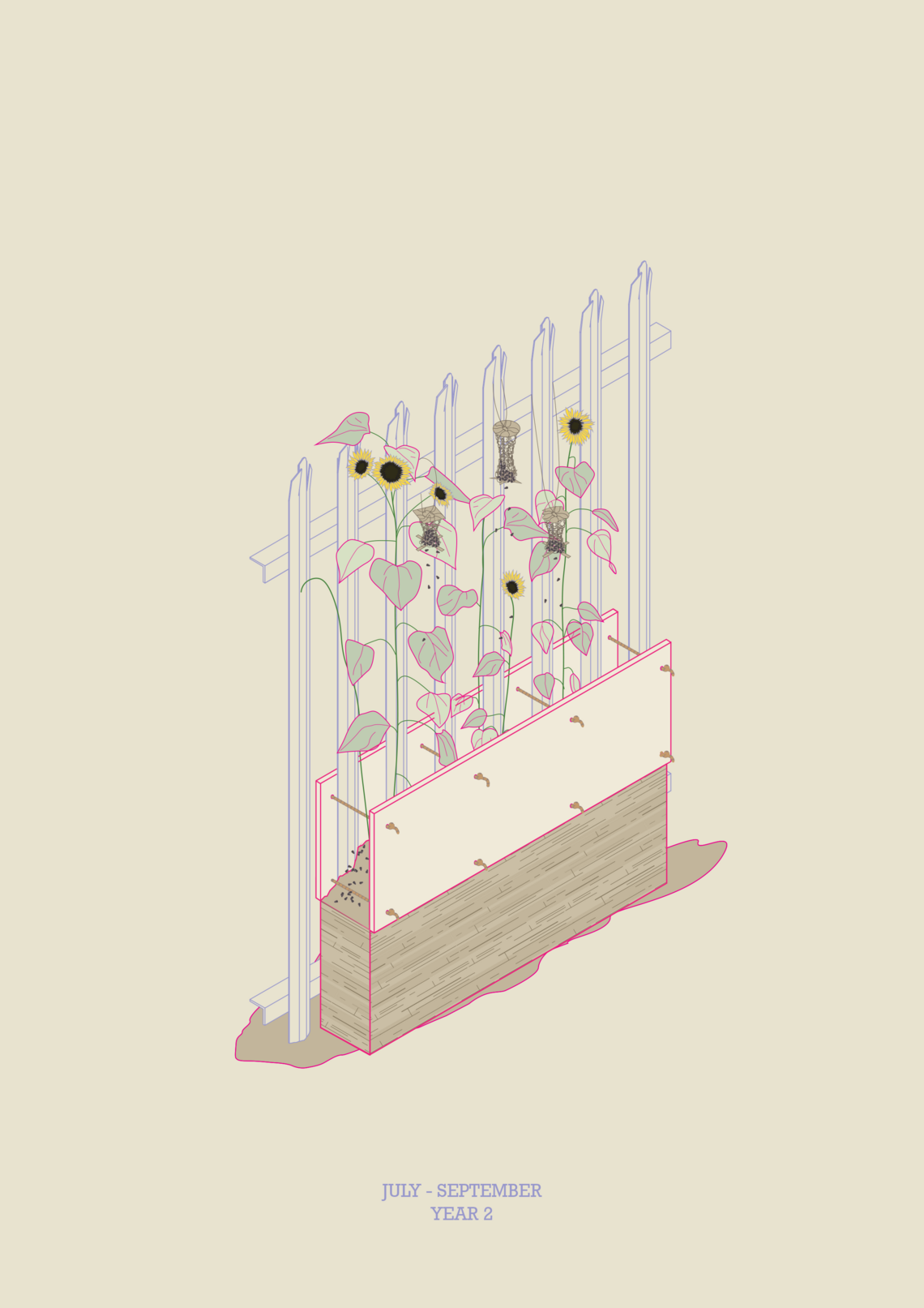

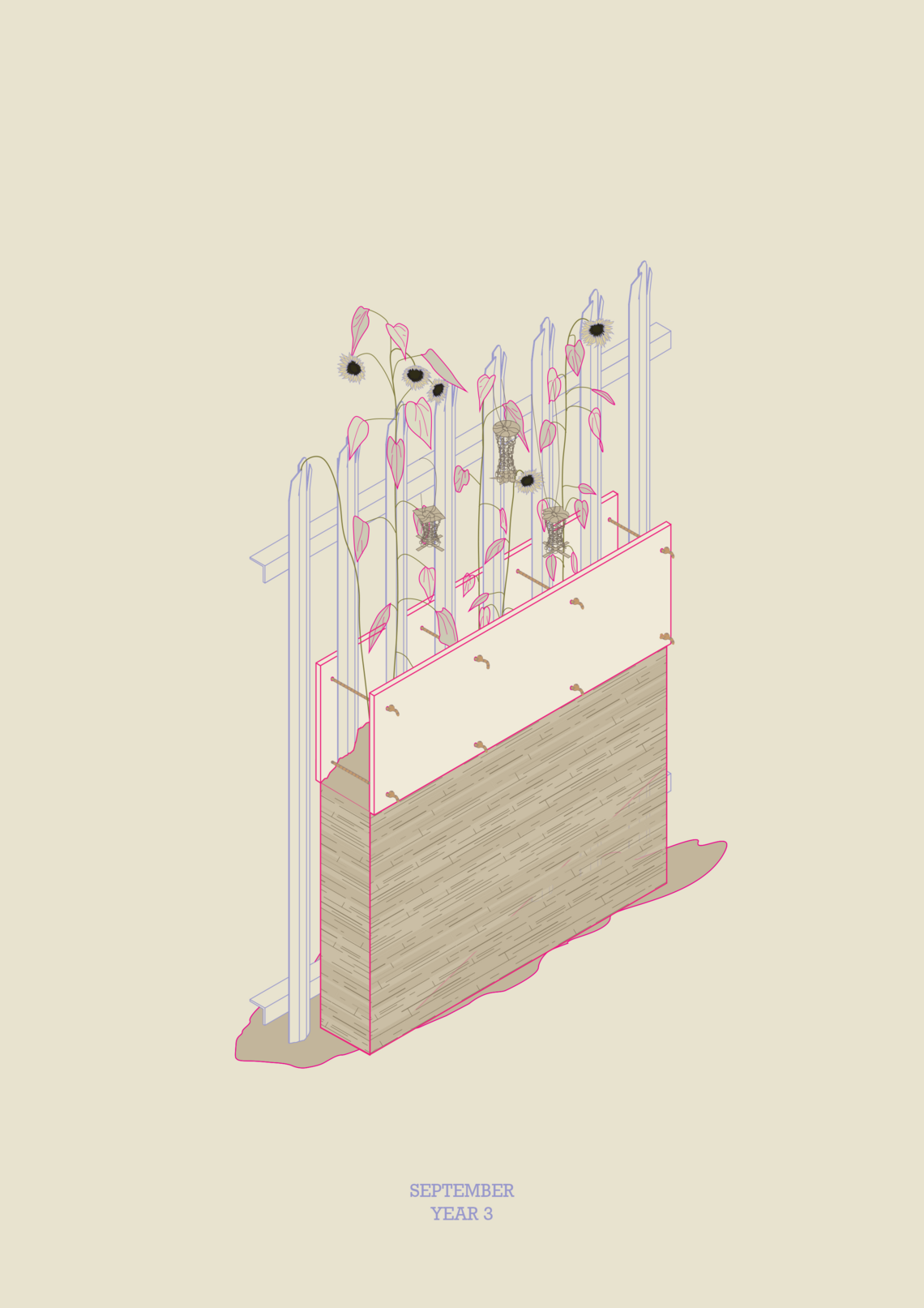

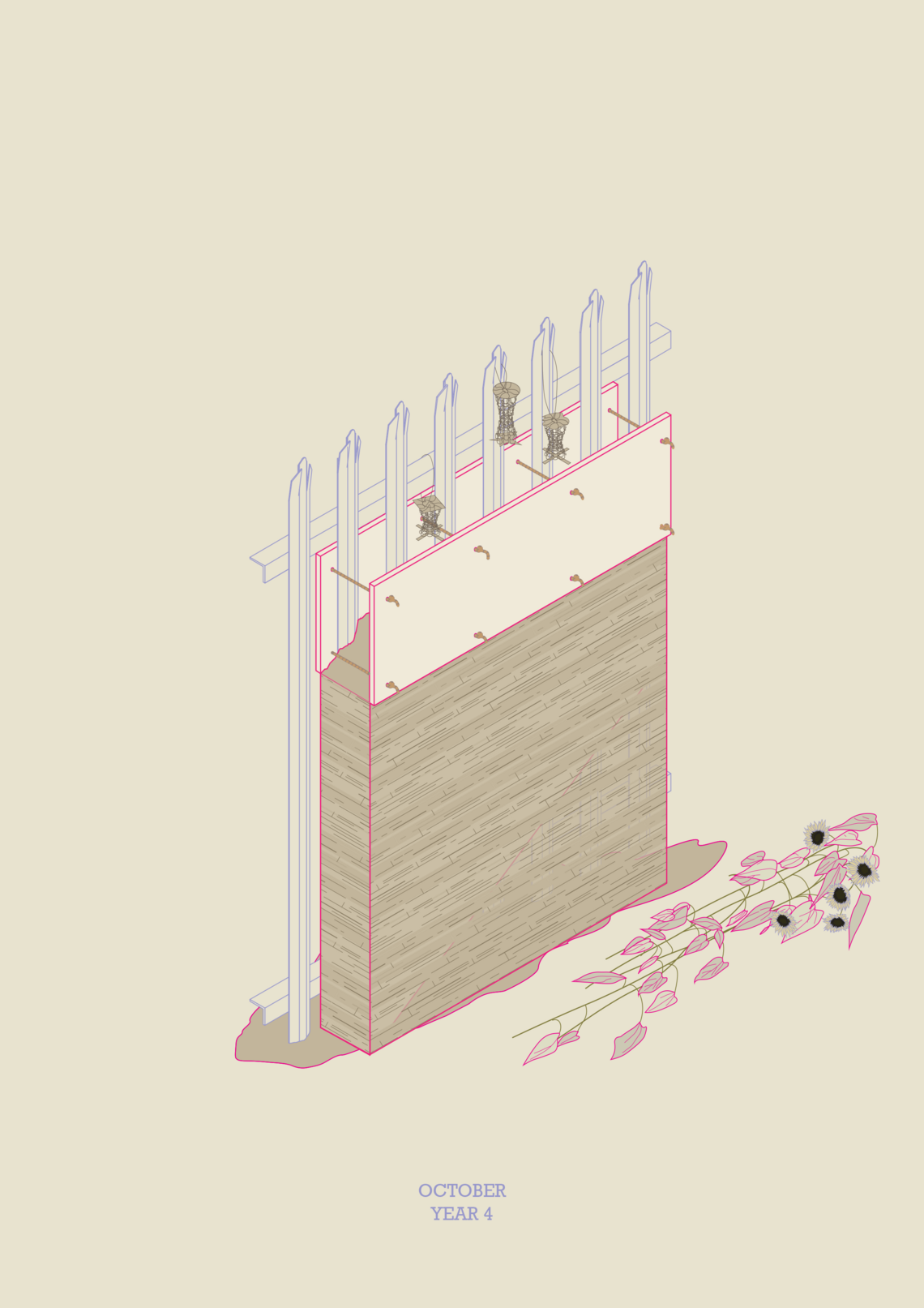

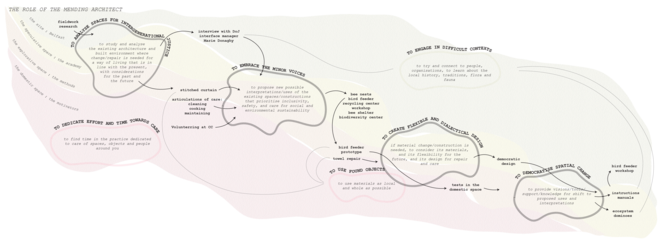

This bird feeder has been crafted as a catalyst for change: if maintained, refilled and cared for, the bird feeder would provide sunflower seeds for bird life on site. If vandalised, deteriorating or simply being whisked away in the wind, the seeds would fall into the ground, where they would sprout and grow into sunflowers. The birds and the flowers allow for the fence to be considered as an amplifier to non-human species, but they also aim to be a deterrent for setting up large bonfires as they would create pollution for birds and flowers. This catalyst has been designed as an initiative for a collaborative workshop between the two youth clubs across the interface, for children between 8 and 12 and their parents. An instruction booklet has been crafted and sent to relevant stakeholders, and includes the motivation for making such bird feeders, step by step instructions, a maintenance guidance, and future possibilities.

Parent-children teaching is a dimension of the project that is quite important in dealing with intergenerational trauma. It has been analysed that anti-social behaviour and drug use by children and teenagers in interface areas have strong correlation to familial relations between parent and children. Knowledge and skill teaching from parent to children has been one way that I have become close to my mother, learned about the hardships in her life, but also seen the positive, the resilience. I have realised that these skill sharing situations were spaces where it felt safe to tackle barriers of trauma.

As architects, when we share our skills with others, we can offer the opportunity for them to envision another way of life, and how to achieve the changes towards it. By sharing our skills, we can democratise changes in the environment.

Catalyst #2: The pallet bee's nest initiative

The second social and material initiative involves creating relations on site between the Falls memorial garden, the pallets used for bonfires and the newly grown sunflowers on the blighted space. Through an external concern of biodiversity and pollination, the initiative involves youth centres from each side of the interface who have previously collaborated to a new collaboration: building pallet bee's nests.

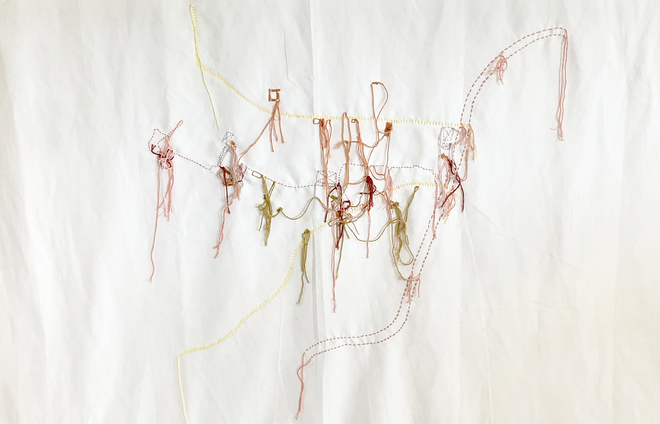

The solitary bee, over the course of a few weeks, mates, lays eggs and builds a nest with pollen which her offspring will feed on to grow into the next generation, the following year. The notion of time reveals itself through the life cycle of bees and sunflowers. Every year, the bees and sunflowers are provided a ground to be cared for. The active, cyclical, action oriented part of these initiatives is important in the act of mending. The space created for the amplification of non-humans requires, and allows, human agency. Over the course of a year, bees, sunflowers, birds, interfaces, memorial gardens, and bonfires benefit from the reproduction of caring behaviours.

An ecological corridor

Through the cumulation of all these initiatives, an ecological corridor can connect the sunflower fields to the memorial gardens, creating larger combined areas, allowing flora and fauna to circulate between the two zones, and reducing urban heat island effects, which impacts the survival of bee larvae.

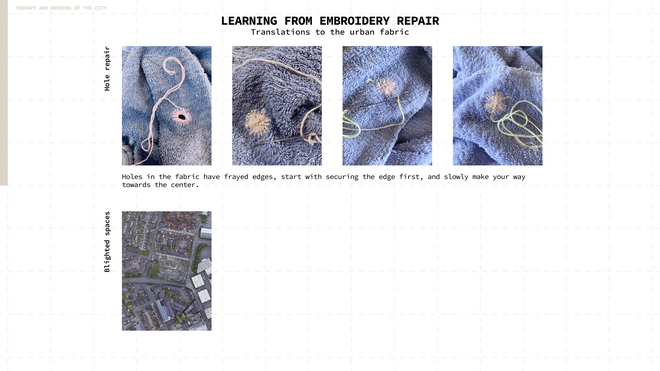

The role of the mending architect

This project in Belfast has been used to inform the creation of the practice of the mending architect. Under this propositional practice, architects can work in a way that makes amends to the earth, while also being mindful of the social consequences of the spaces that are and have been built. So instead of building new, the role of architect can shift towards engaging into crisis contexts, where mending is needed, analysing and researching thoroughly spatial, political, and social context, proposing new interpretations or uses of the existing space, and with design that is delicate and considerate of minimal materials, providing the tools for the work to be reproduced by minor voices, using acts of care, for new generations of humans and non-humans to live differently.

Det Kongelige Akademi understøtter FN’s verdensmål

Siden 2017 har Det Kongelige Akademi arbejdet med FN’s verdensmål. Det afspejler sig i forskning, undervisning og afgangsprojekter. Dette projekt har forholdt sig til følgende FN-mål