weaving-with

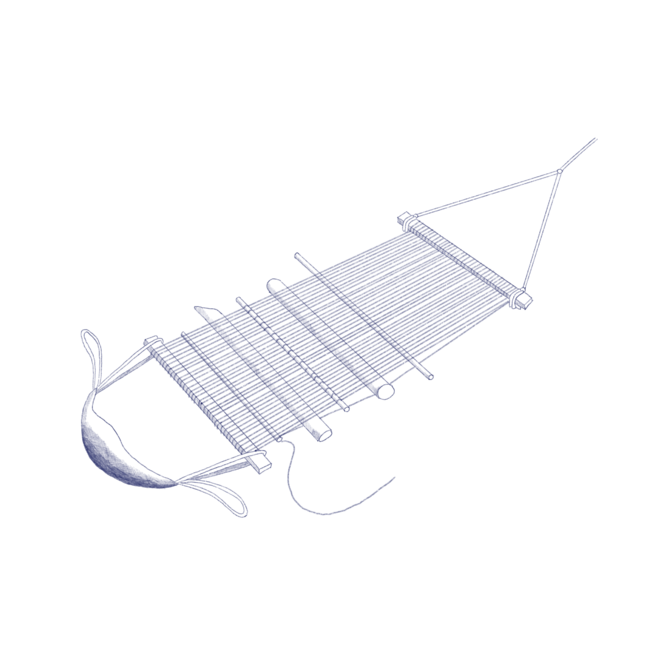

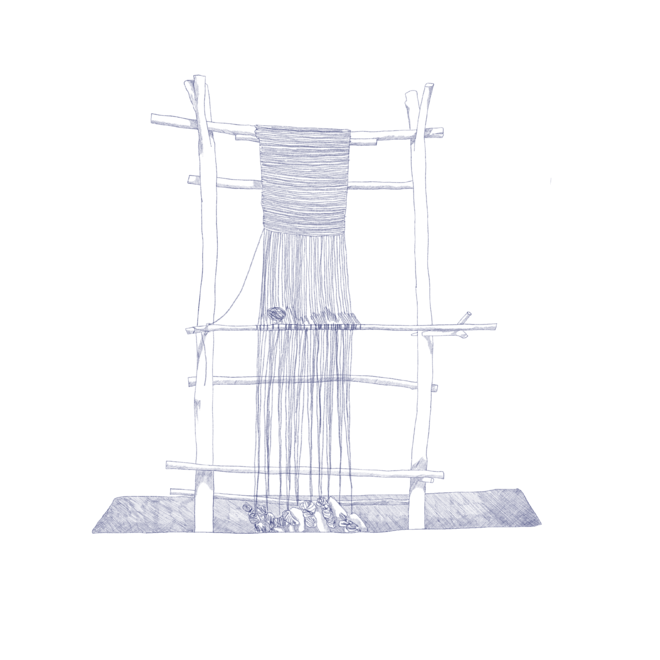

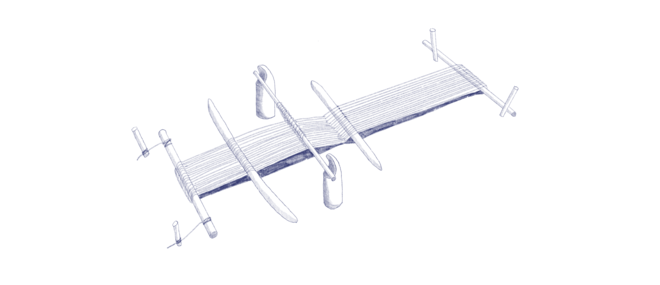

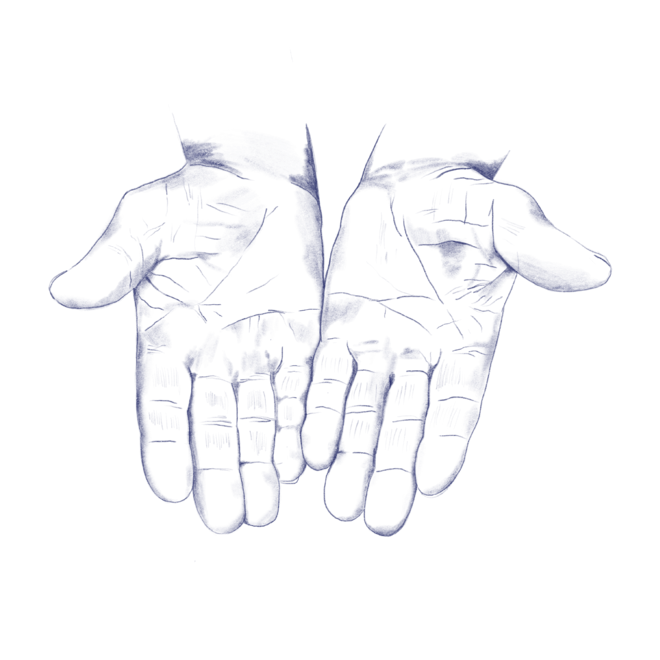

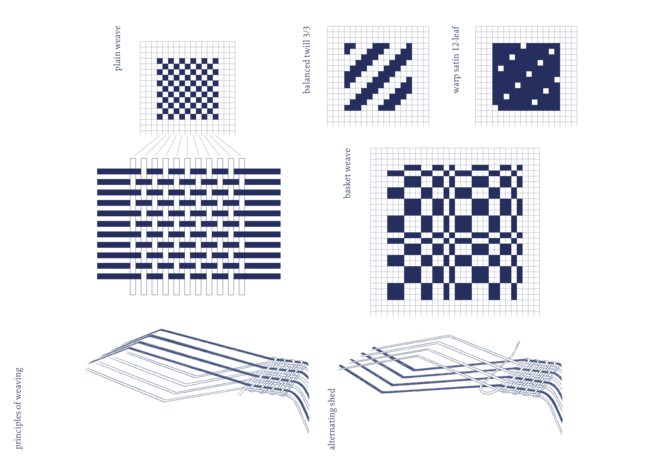

The weaving of fabric has been an integral part of society since the dawn of humanity. Mythological figures and gods of weaving played important parts of the cultures which dominated the planet—from the Ancient Greeks’ Athena to the Sumerians’ Uttu. These gods represented the female population, the ones in charge of supplying the household with cloth, as well as a bartering device during times of war or hardship, cementing women as domestic economic contributors. Weaving itself has not changed much since the development of the loom, its basic principles remaining the same. Weft goes over and under the warp threads, which are provided with tension either by loom weights and gravitational forces, or by their binding around the loom itself. This tension creates the structural stability of the fabric, providing a framework on which to assemble stories, record historical events, and maintain traditions of culturally significant patterns. Weaving-with utilises weaving as an agent for thinking and making, for informing the intentionality of an architecture as well as being a point of departure for propositional manifestations in Belfast, Northern Ireland, a post-industrial city layered with assemblages woven around flax and linen.

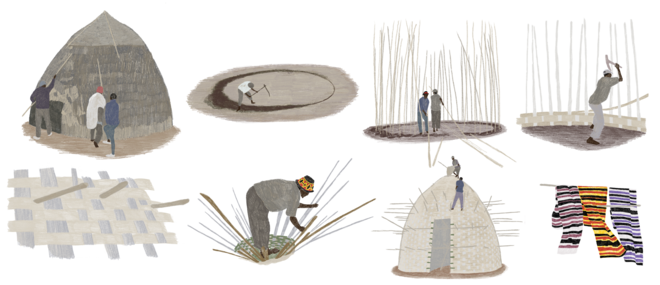

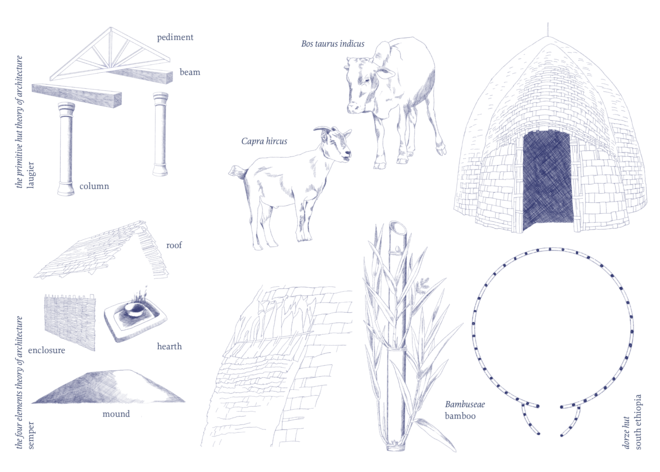

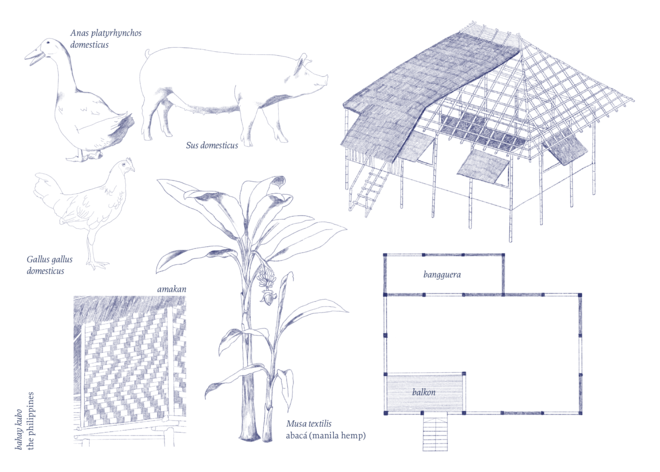

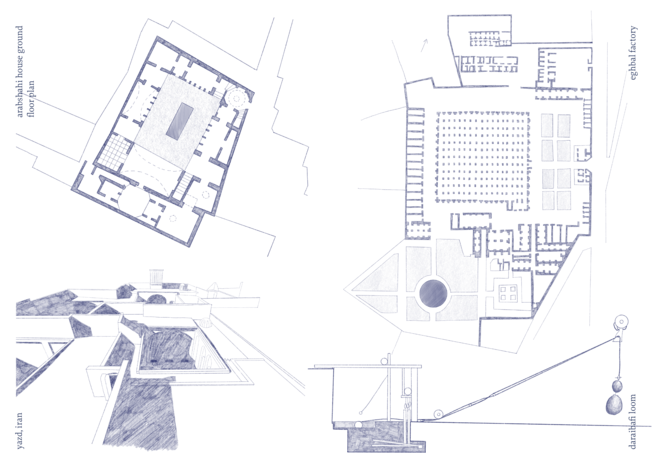

Semper’s Four Elements of Architecture include a woven enclosure—a direct progression of tree-branch woven fences and nomadic fabric tents and carpets. Evidence of this can be seen in current-day domestic architecture such as the Filipino Bahay Kubo and the South Ethiopian Dorze Huts, among others. Both utilise bamboo as a flexible building material, capable of withstanding the torque weaving imposes. Both have weaving traditions embedded in their cultures, influencing their architecture and relationships with their surrounding flora and fauna.

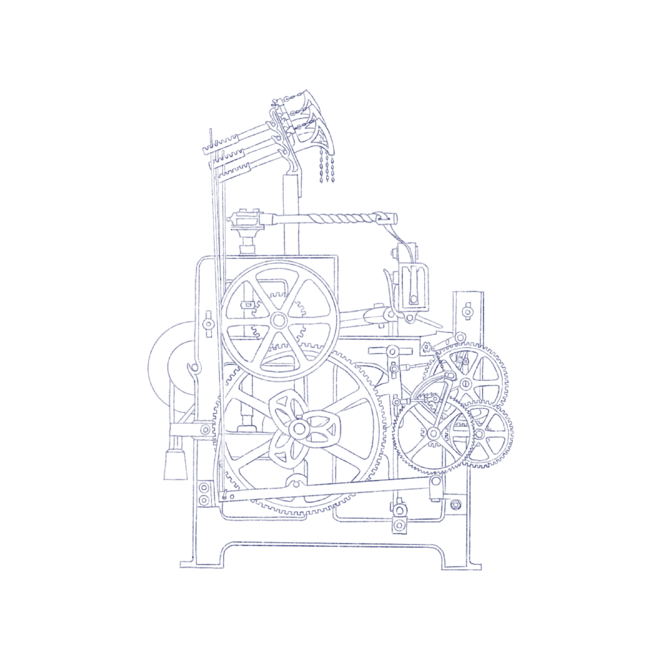

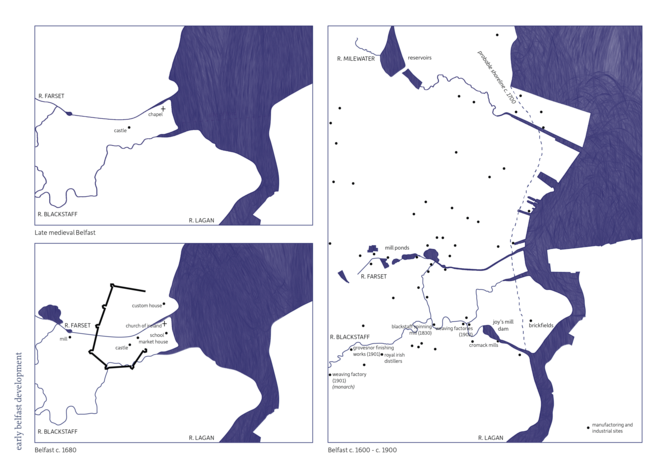

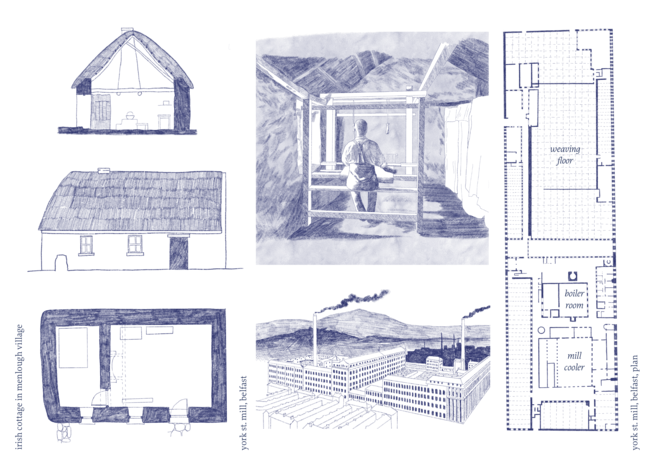

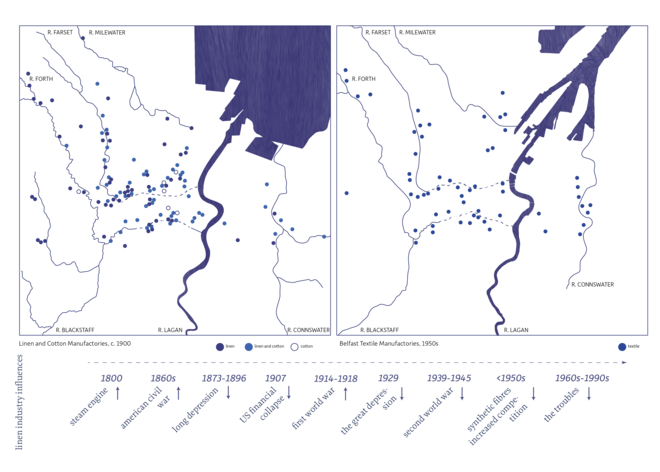

In Ireland, and in particular Ulster, spinning flax and weaving linen played a major role in the economy, even a few hundred years prior to the industrial revolution. In the late 17th century, a domestic network of female spinners and male weavers sold their linen to merchants and later on, bleachers, who would bleach the brown linen in bulk and sell it onwards. As industrialisation propelled a mass migration of workers into cities, and especially Belfast, women became the primary weaving workforce in mills around the city. The craft became a well organised manufacture, establishing Belfast as the largest producer of linen in the world, and the moniker of Linenopolis. Today, all but one of the weaving mills have disappeared, leaving only scattered physical remnants as memories of the once prolific industry.

Belfast was founded in 1613, with the construction of the Belfast castle on a defensive site between the river-mouths of the Farset and Blackstaff on the west bank of the significantly larger Lagan river. In 1640 its population barely reached 500. Up until the 18th century, the land Belfast lies on was too waterlogged to allow for any significant growth of the town. A formation of a sandbar across the Lagan aided in the settlement’s expansion to the west. By the 1720s Belfast became Ireland’s third busiest port. Before 1853 the town’s economy was mostly based on exports of butter and salted beef. In the late 17th century the introduction of improved methods of weaving by French Huguenots immigrants completely changed the town’s industrial landscape. It had only truly become an important centre of industry in the middle of the 19th century, with linen production at the core of its rapid industrial growth.

Linen was joined by shipbuilding and the two industries, their byproducts, workforce, and infrastructure soon formed an assemblage of production around them. For example, the flax left over by the linen industry was used to make ropes and nets for ships. The use of more complicated machinery drove the emergence of a thriving engineering industry as well as many foundries. This assemblage was the driving force behind Belfast’s evolution as a city, as a space of labour and work. Today it is littered with the remains of the industries which slowly disassembled during the last seventy years.

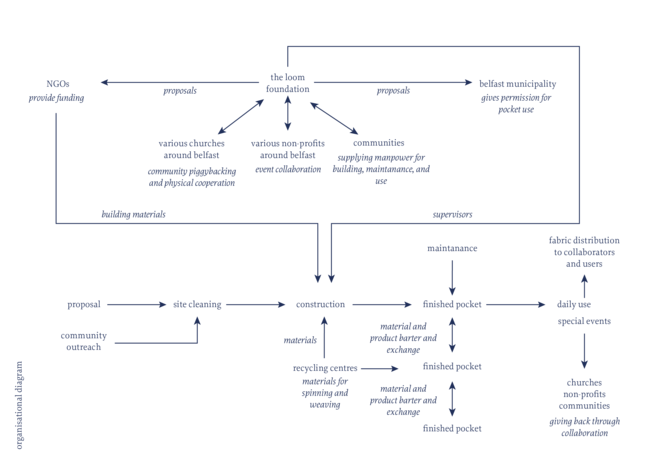

Weaving is re-introduced to Belfast through soft spaces. The heritage of the linen industry is alive in memories and artefacts scattered all over the city. Descendents of linen workers carry the past within them, though they have probably never attempted to make fabric themselves. People in communities which have lived in Belfast for more than a hundred years, passing down stories of the mills, the conditions in which they worked, the strikes which they took part of, and the artefacts they produced. Some may still have some remnants of table cloths or jacquard, stored in their attics. I propose connecting the mostly forgotten historical, industrial, and personal narrative through a tangible activity or craft, weaving. Taking part in an integral part of Belfast’s history, something which shaped the city into what it is today.

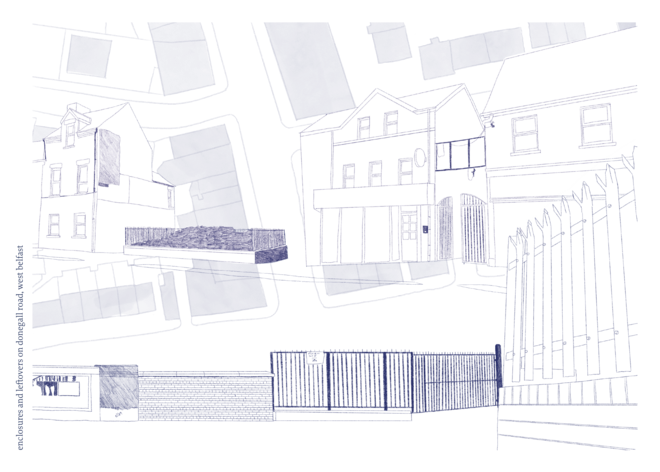

The pockets I chose to look at are leftover spaces between buildings that are abundant in Belfast. Some as a result of two ends of the street meeting awkwardly, other times because of demolition and rebuilding which leaves extra spaces between gables. Mostly, these spaces are left abandoned in Belfast, fenced off, not even providing passage through them. I chose to focus on these spaces to inject some softness into the harsh Belfast reality. A reality influenced by the brutal history of the Northern Irish conflict, memories of which remain on the streets. Since the Troubles, almost all public space in Belfast has been fenced and gated. Parks have closing times and are huge, intimidating, and uninviting spaces. On the street there is nowhere to linger. Places are either private or institutional. Public, non-sectarian spaces are basically non-existent. Especially outside the city centre. I suggest creating spaces free for interpretation and manipulation, ones which can morph into what the community requires at a particular time.

Donna Haraway uses weaving as a model system for sympoiesis, “making-with”—humans and non-humans living and dying together on earth. She asserts that the cosmological performance of weaving is crucial for

My woven methodology consists of thinking and making within the contexts of weaving, using weaving sensibilities, and metaphorically and literally weaving fabric together with architecture and the city.

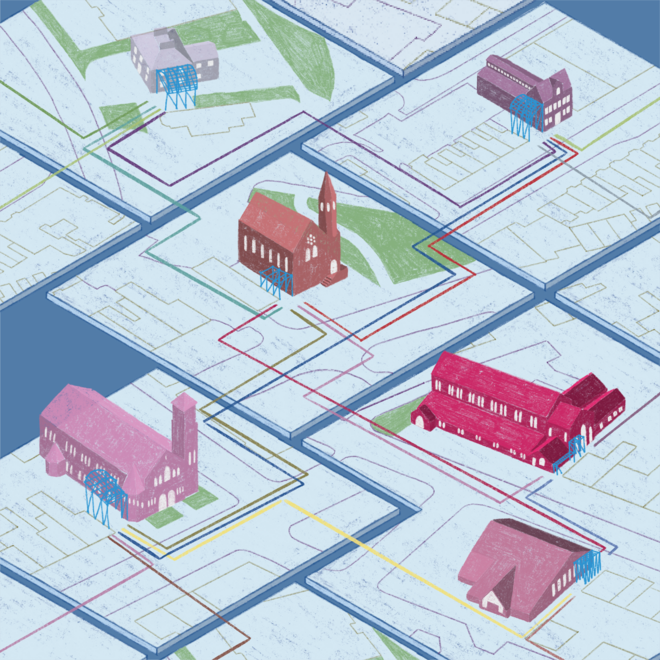

Northern Ireland is a very religious country. 80% of people associate themselves with some form of organised religion, with christianity being the dominant one by far. In Belfast there are hundreds of churches, both catholic and protestant. My proposal utilises leftover spaces, or pockets, which exist in between churches and adjoining buildings. I chose to focus on these spaces in particular, as a way of piggybacking on existing centres of community which house different activities throughout the week, as well as being a house of worship. The established churches provide a backbone of groups of people from the neighbourhood which are willing and wanting to participate and foster communal relationships. Ones which will hopefully cooperate with the initiative of adding outdoor, public space next to the church that can be used in different ways, revolving around the acts of weaving, fabric production, and artistic textile expression. The spaces are kept and maintained by the communities, who may do with them as they please, changing their use and function to suit their needs.

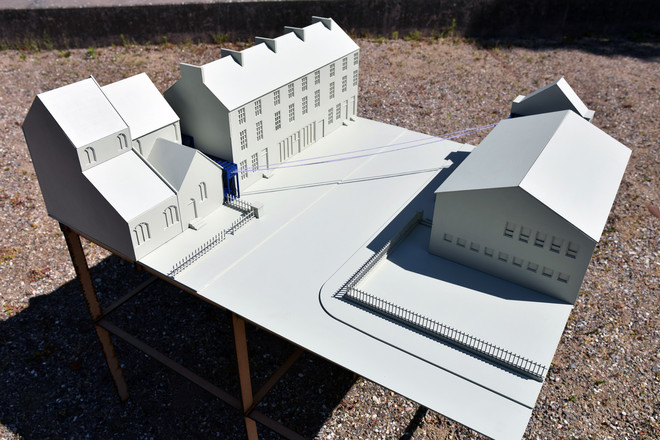

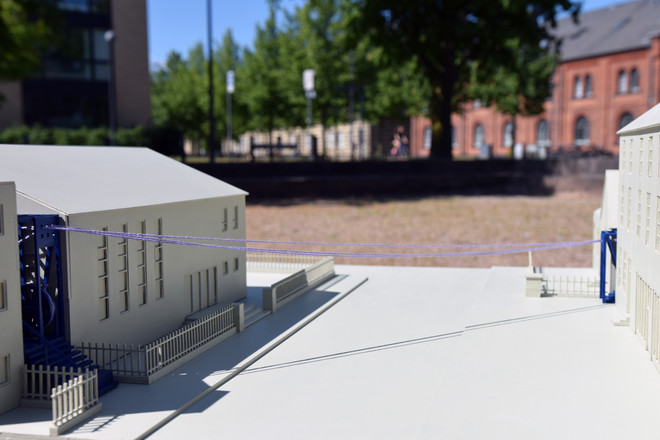

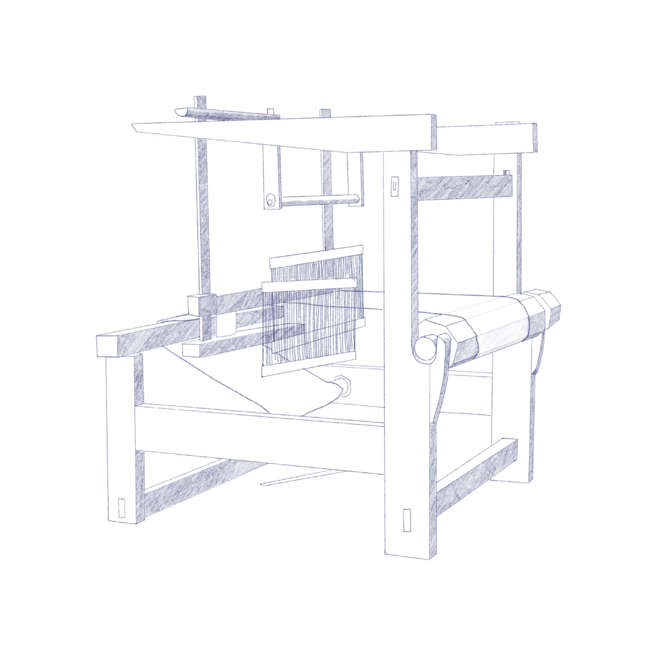

The pockets use the existing gables as a structural foundation. They are constructed of reclaimed leftover timber, and a modified ‘Belfast truss'—an industrial era timber truss invented in Belfast at the middle of the 19th century. This type of interlacing truss used leftover pieces of timber from the shipbuilding industry to create huge industrial hangers spanning up to 30 metres. The trusses were built on site, and are very easy to assemble. In the pockets, they have been modified to accommodate the smaller spaces, and yet they are still used to create a large roof span without the need for intermediate columns. The curved roof can be easily covered with fabric or other roofing material. The loom is hung from the beams of the truss, while the floors are supported by the side columns. The design itself is very simple, easy enough to build by people who do not have much, if any, experience building such structures.

In these pockets, looms and spinning wheels will occupy a part of the space, providing a performative, self-expressive function to the assemblage forming around the city. The various pockets have different kinds of looms which produce diverse types of fabric, according to the spatial dimensions of each pocket. The pocket communities will trade fabric and yarn with one another—at first perhaps cloth for dressing the pocket itself, creating a roof or curtains to divide the space. As their production continues, the fabrics can be distributed among members of the community as well as the various collaborators. The fabrics themselves may change from utilitarian to expressive, used for activism and communal storytelling, spilling onto the streets. While the looms are used for weaving, the spaces around them house different communal activities and gatherings, to each community’s desire.

![great victoria st. pocket section [1:50]](/sites/default/files/styles/large_wide/public/imported-file/section-images/10-01.png?itok=vaNqoGL1)

The connections between these pockets require communal cooperation and make up an assemblage of fabric production and communal interactions around Belfast. The framework allows for family histories to rise to the surface of civic society, reminding Belfast of what it once was, through the extroverted weaving in the streets, replacing the smoke rising from the chimneys of closed factories a hundred years ago.

“Let us never forget that there is an architecture of architecture. Down even to its archaic foundation, the most fundamental concept of architecture has been constructed. This naturalised architecture is bequeathed to us: we inhabit it, it inhabits us, we think it is destined for habitation, and it is no longer an object for us at all. But we must recognise in it an artefact, a construction, a monument. It did not fall from the sky; it is not natural, even if it informs a specific scheme of relations to physis, the sky, the earth, the human and the divine. This architecture of architecture has a history; it is historical through and through. Its heritage inaugurates the intimacy of our economy, the law of our hearth (oikos), our familial, religious and political ‘oikonomy’, all the places of birth and death, temple, school, stadium, agora, square, sepulchre. It goes right through us [nous transit] to the point that we forget its very historicity: we take it for nature. It is common sense itself.”

-Derrida, ‘POINT DE FOLIE — MAINTENANT L’ARCHITECTURE. Bernard Tschumi’, 65.

![models [1:50]](/sites/default/files/styles/large_wide/public/imported-file/section-images/dsc_0098.jpg?itok=9Fvw4G9J)

![pocket assemblage fragment plan [1:2000]](/sites/default/files/styles/large_wide/public/imported-file/section-slideshow/10-10.png?itok=ZJsFhkUb)