Fritids Pannan

FRITIDS PANNAN

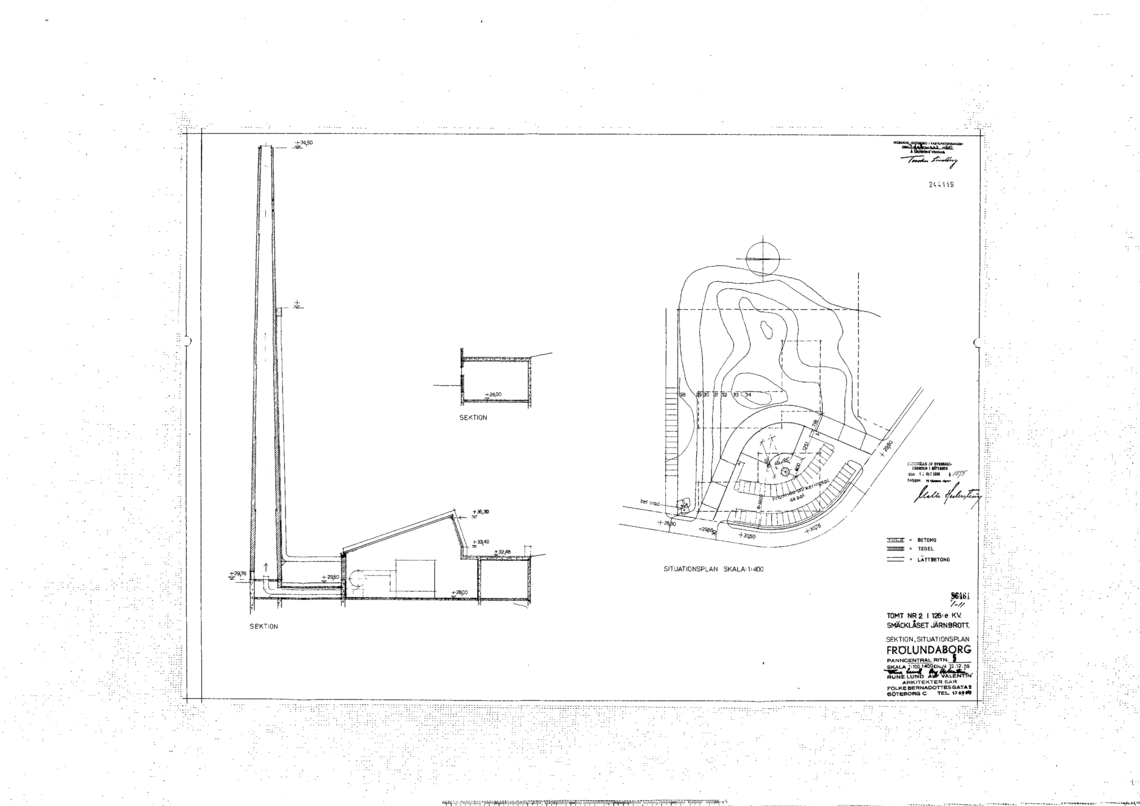

after-school program from 'panncentral', boiler facility

[[{"fid":"363505","view_mode":"top","fields":{"format":"top","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Illustrated text [Panncentralen] with pencil, using a quirky, industrial aesthetic.","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"Panncentralen (from The Map of Panncentralen)"},"type":"media","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-top"}}]]

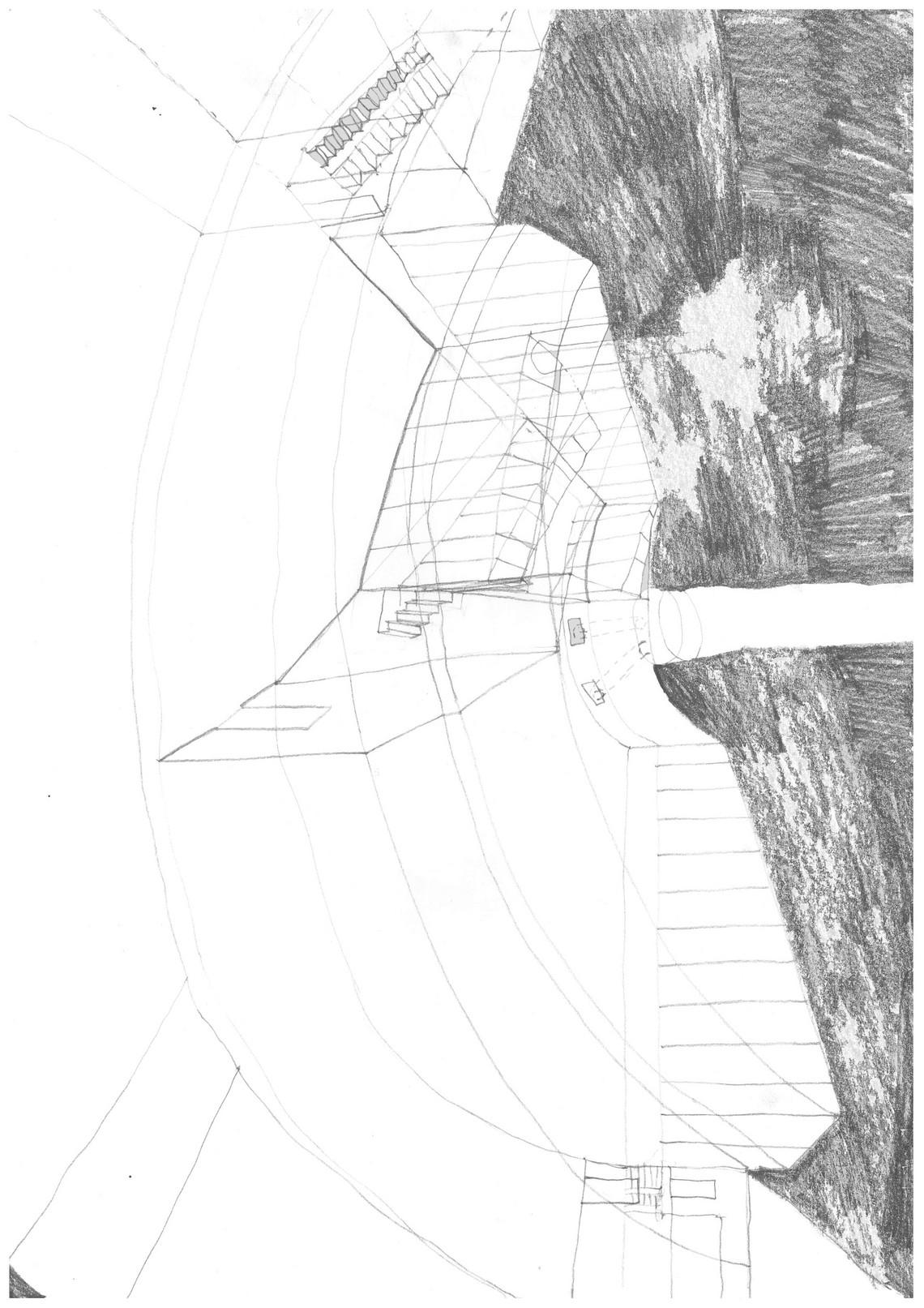

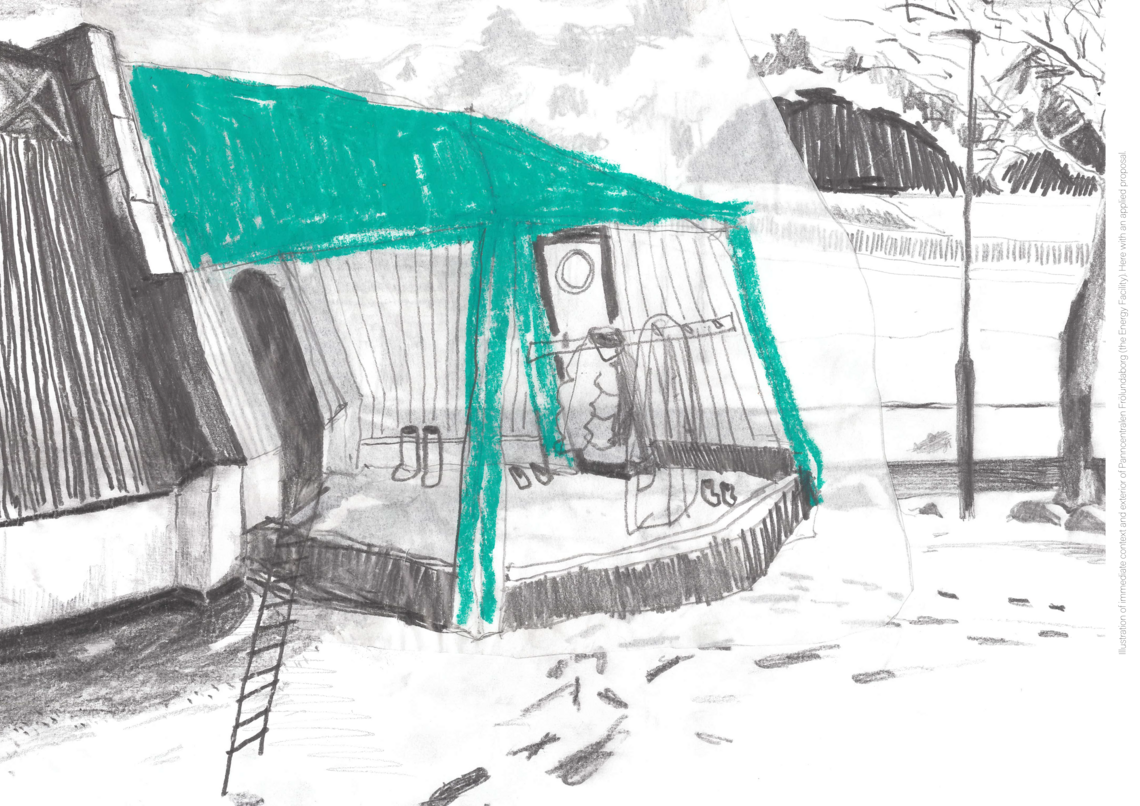

Fritids Pannan is a project that has sprung from research on inaccessibility to second home culture in a Swedish context. It covers themes of cross-programming, play with risk & the theoretical realm of re/de-territorialization. It houses an after-school program in a functioning geothermal energy facility, where summer camp & the seasonality of a garden are a key to the second home.

[[{"fid":"363240","view_mode":"top","fields":{"format":"top","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Historical photograph of children playing outdoors, pushing some materials up a hill to build a wooden fort","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"Children in Play"},"type":"media","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-top"}}]]

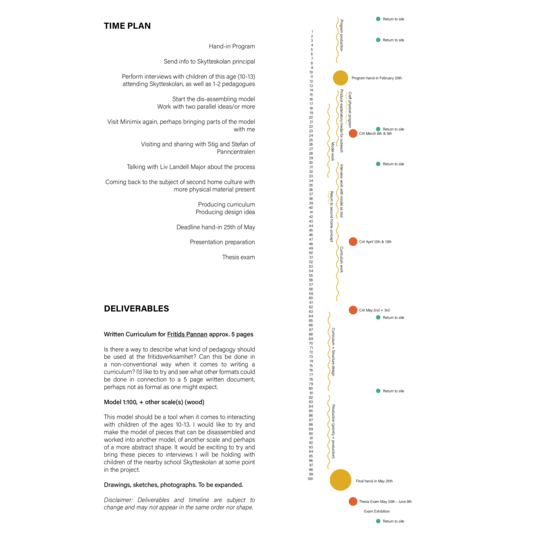

To be able to frame the project, a curriculum has been written. It is aimed at the pedagogue who might join the proposed universe of Fritids Pannan. Below, an excerpt:

______________________________________________________________

Curriculum for Fritids Pannan: Why, what, when, where, how, and with whom to learn?

Dear pedagogue,

Thank you for joining us at Fritids Pannan! We, the people who work here already, will firstly introduce you to our thoughts on the form of curricula, then follow it up by telling you a bit about our premises, the useful aspects of our after-school program being placed in an active energy facility, and what we aim to do for our kids at Pannan. Enjoy, and let us know if you think we should add something that you’ve experienced is a big part of the place and of our goals.

[..]

Why?

Why is Fritids Pannan different from the other after-school programs, and how does it perform with this in mind? Through what tools do we get an explorative way of thinking and evolving here that cannot be found elsewhere? Why do we need these practices and learnings?

It is often mentioned how important the after-school programs’ existence is to the development of children, their confidence, and their presence in society.[1] Especially children and youth in economically precarious situations are supported through the work of the after-school programs, as they might not have enough funds for other after school activities. It is sometimes discussed whether the after-school program is there to strengthen the added value of an individual, or if it is simply enough to strengthen their self-value on their journey to adulthood.[2]

Fritids Pannan has the potential to be part of this structure where independence and self-esteem is implemented to corroborate the way youth carry themselves throughout their school years and onwards. This center of learning has a tight connection to the reality of the practical because of its placement – in the frame of an active energy facility building.

What?

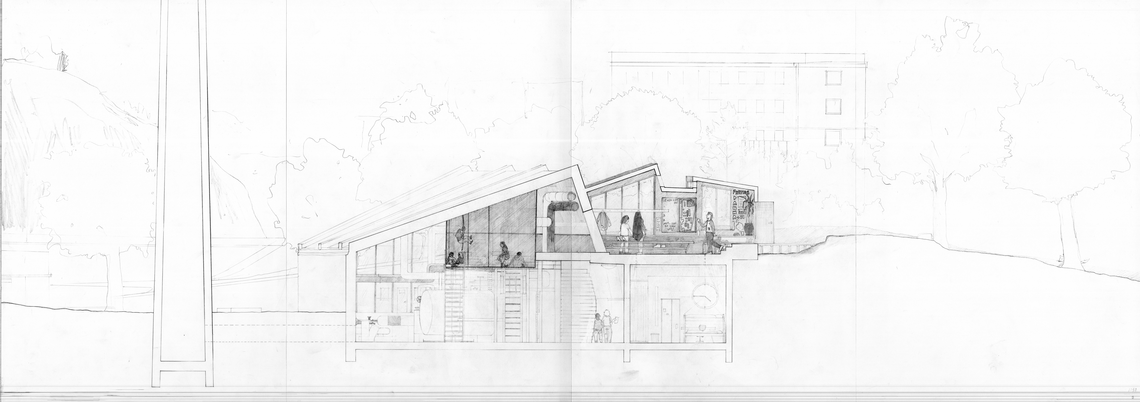

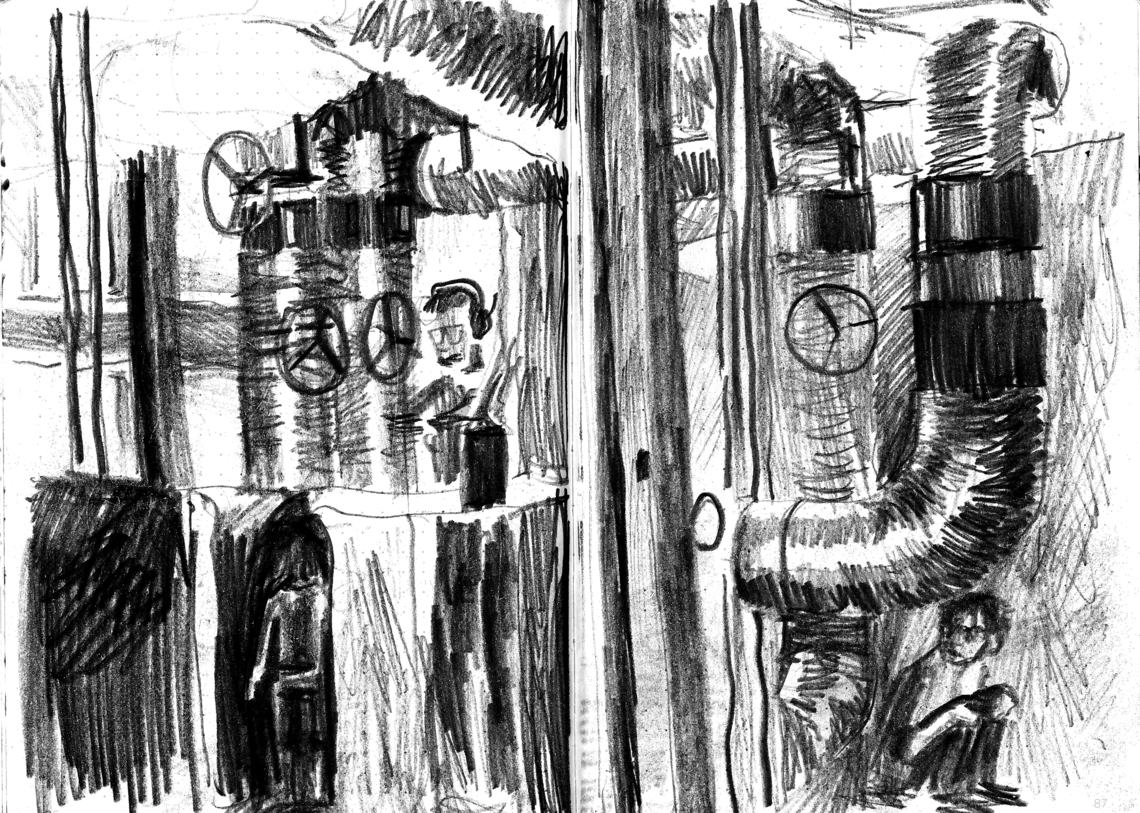

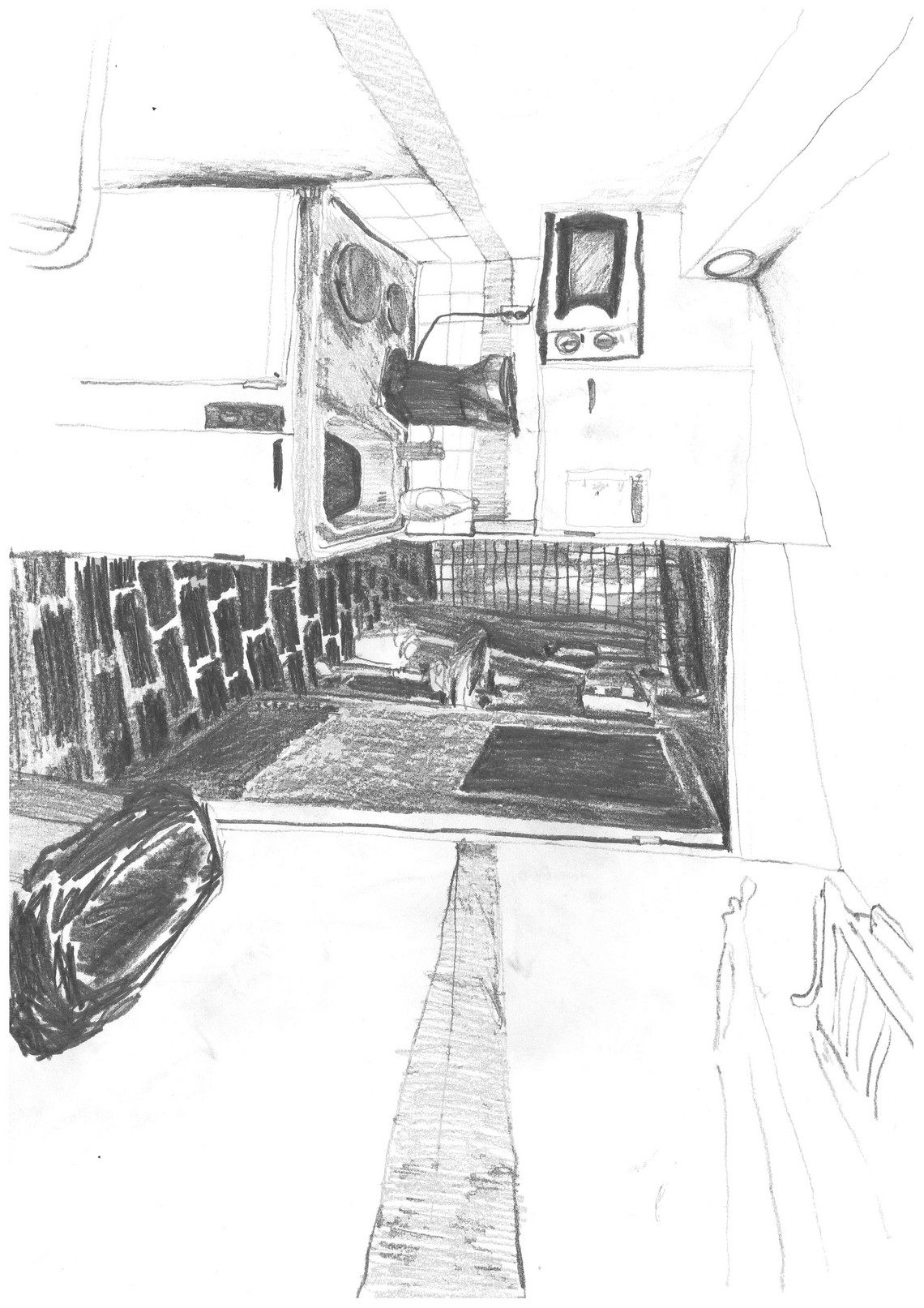

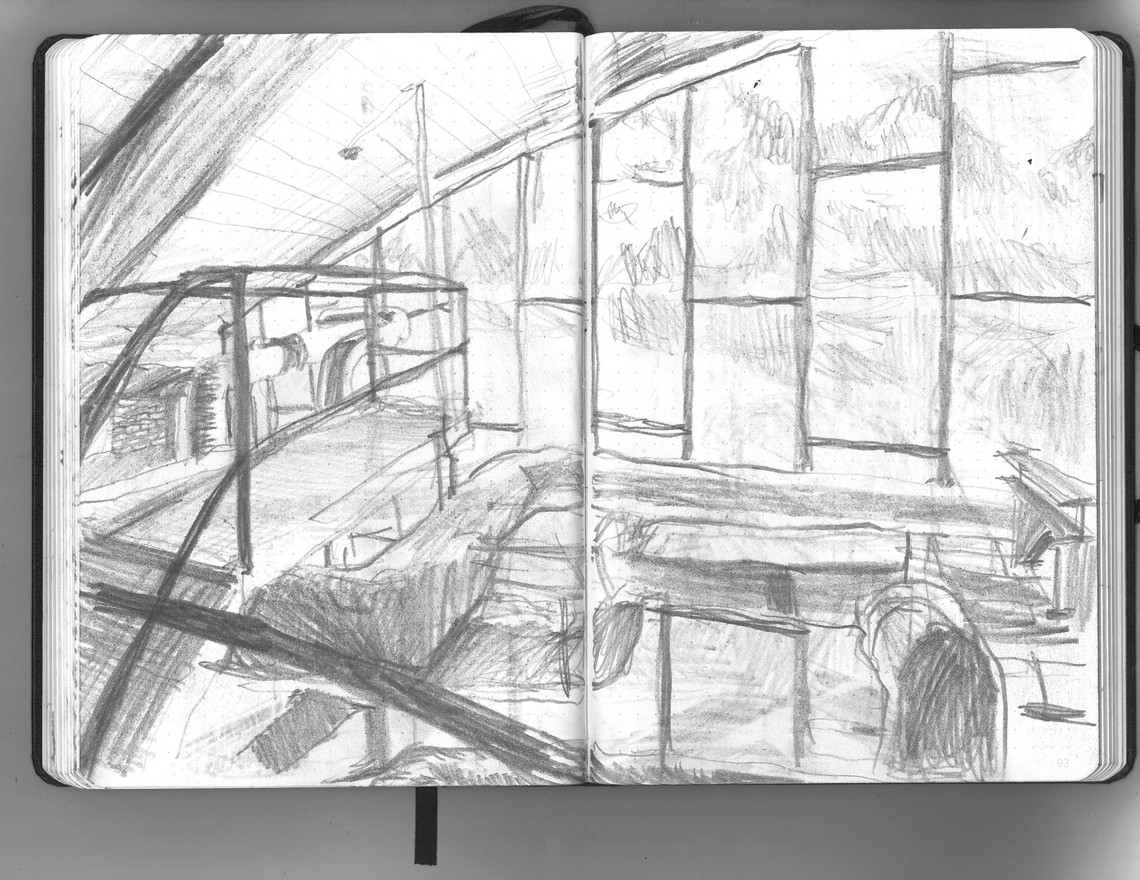

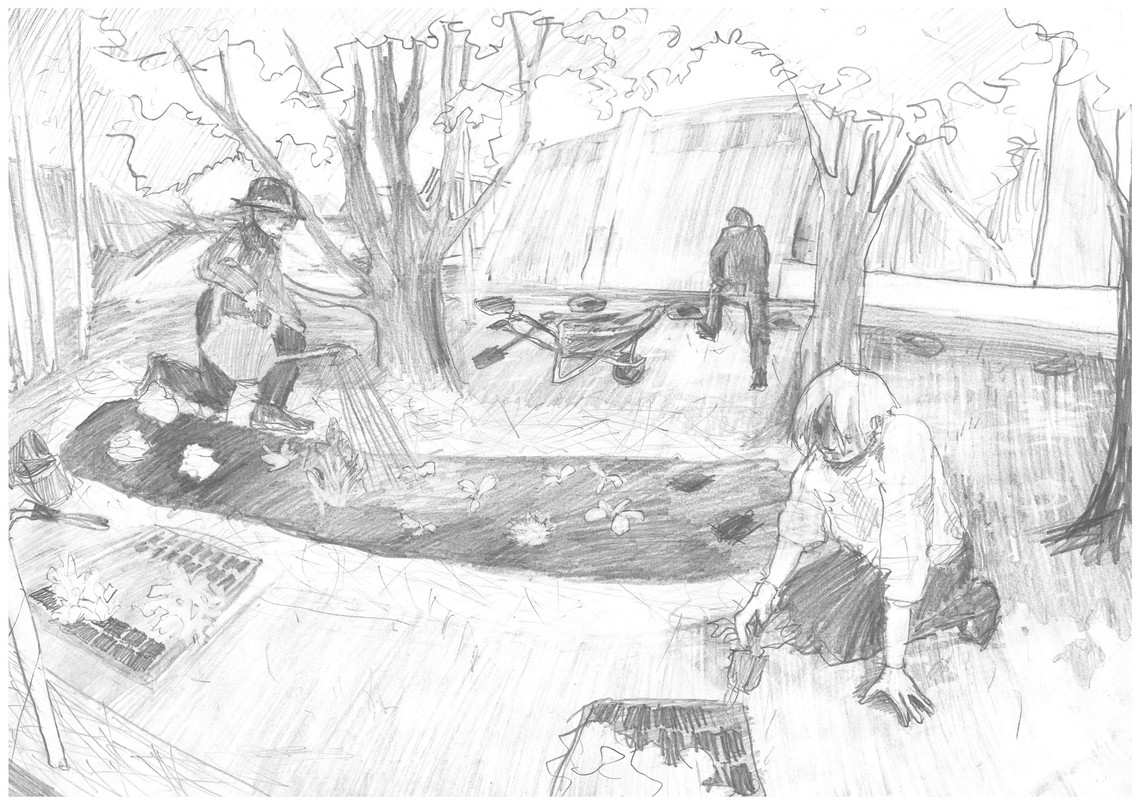

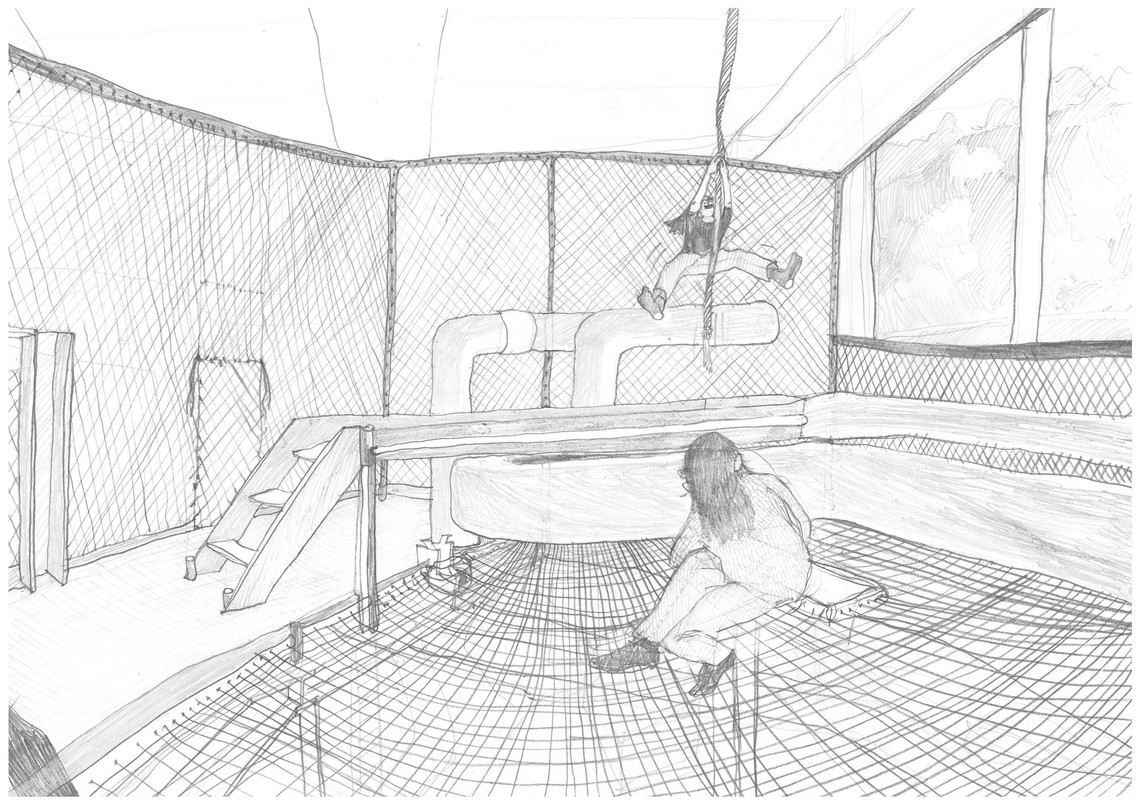

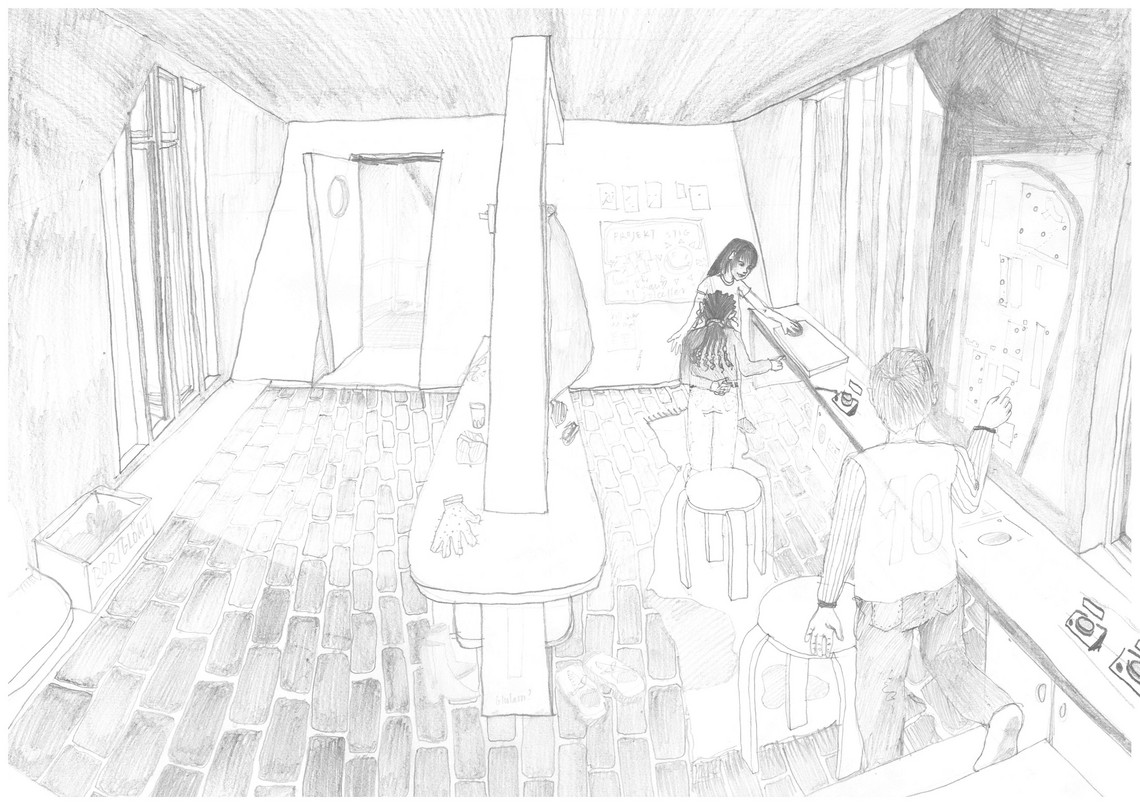

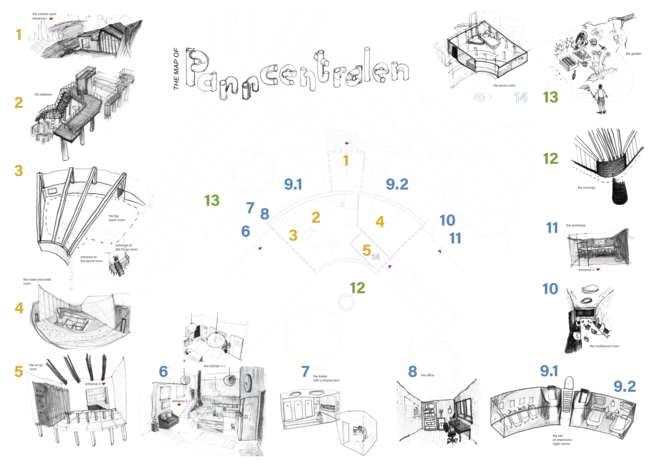

We and our curriculum aim to host youth from the ages of around 10 to 13 (grades 4-6) in school, to learn a more self-sufficient way to behave, move and act. To be able to work with the children that attend our after-school program, the premises hold spots of activity that ask them to maintain, care and uphold a process (like in the garden), which aspires to consolidate the relationship between the different time intensities of the place. There are spaces for igniting curiosity and hosting instructional and cooperative actions for the youth to initiate co-activities (like in the control room). They span across the physical space, and work with the specific location, leading outsiders to our space as well as entertaining and educating those already introduced.

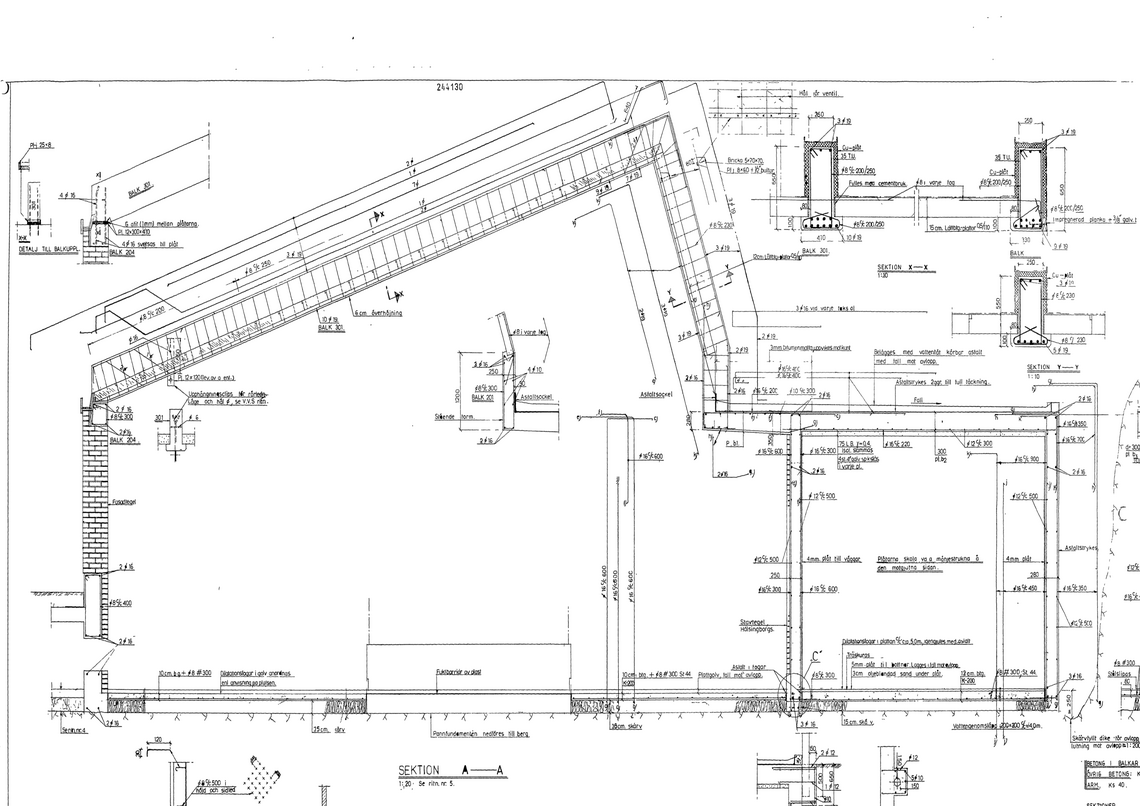

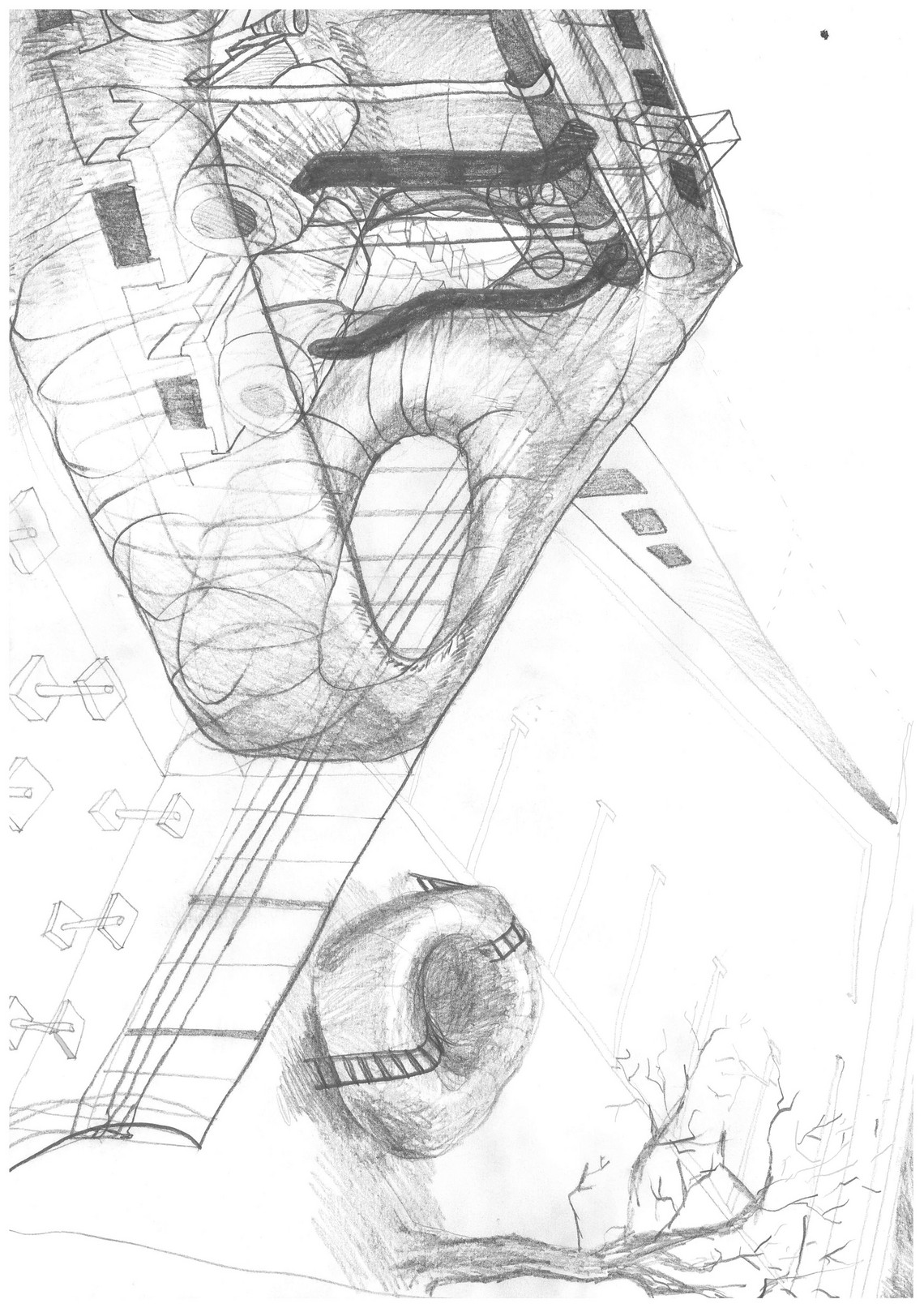

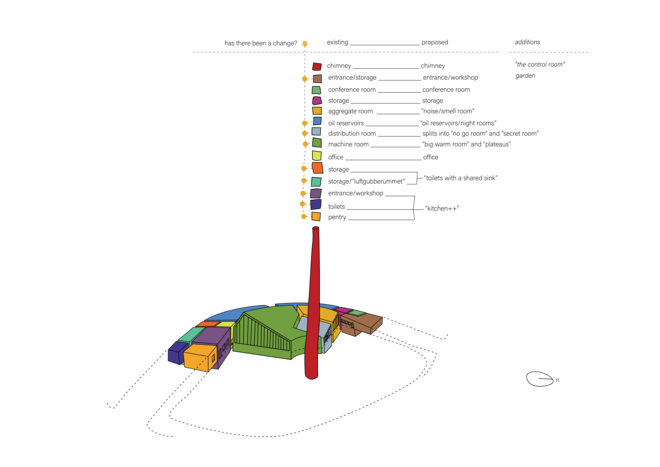

Fritids Pannan and the summer camp/“kollo” both have an architectural presence in the pre-existing facilities we use. The original use of the building is not suppressed, nor overruled by the introduction of the after-school programs. Instead, the rooms either fully occupy (the no go room) or partly and foremostly occupy the spaces (the noise and smell room, the workshop, the conference room, the big warm room ground floor) with the original use. The instances where the after-school program is more present (the plateaus, the control room, the old oil reservoirs/the night rooms) contrast to the ones where they are the main and only users (the secret room). The third type of space would be the equally used ones (the toilets with the shared sink, the office, the kitchen ++, all entrances).

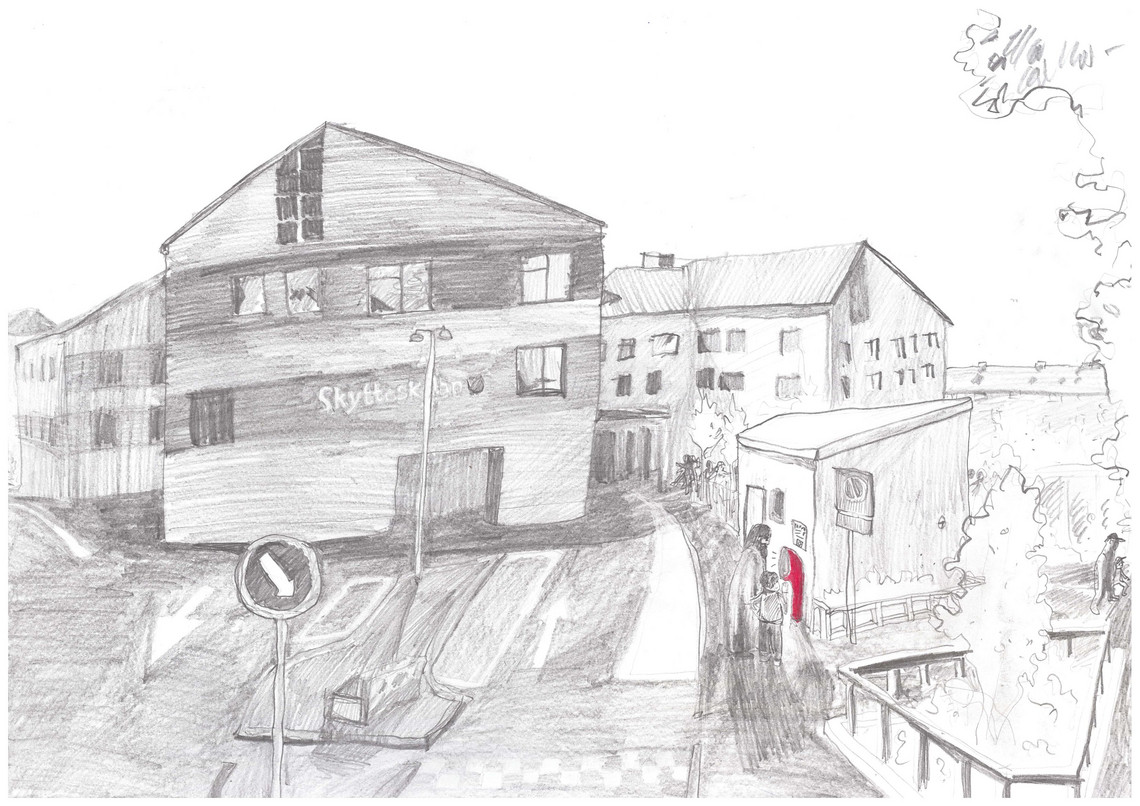

Together with the outdoors and the proximity to Skytteskolan, our after-school program can make use of the on-site potential to benefit the children in question. The energy facility can in turn be in favour of the presence of the after-school program with their connection to the local users of their product and process. This will in turn make sure that knowledge and engagement in their work can be sustained in future generations. Because of the way the energy facility was started, by and for the local users and inhabitants of the area, it can be upkept in a sustainable way.

_______________________________________________________________

The curriculum can be read in whole in the attached PDF "Curriculum".

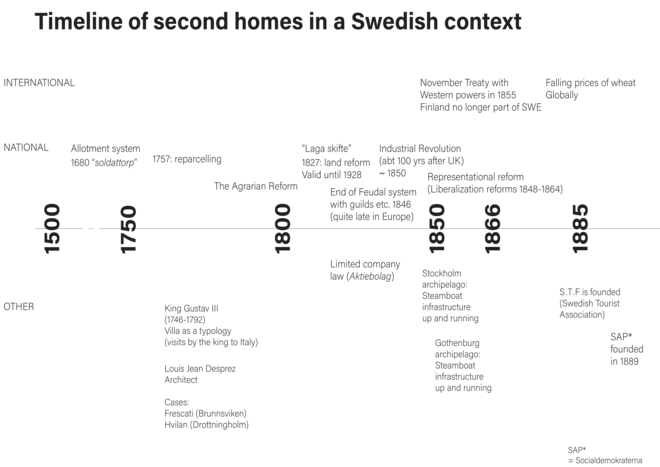

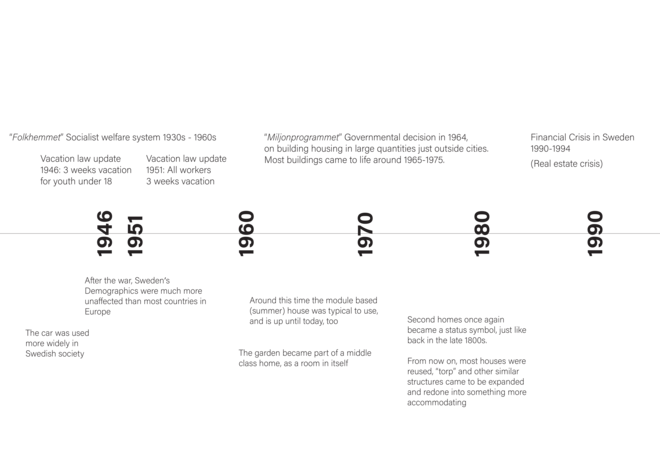

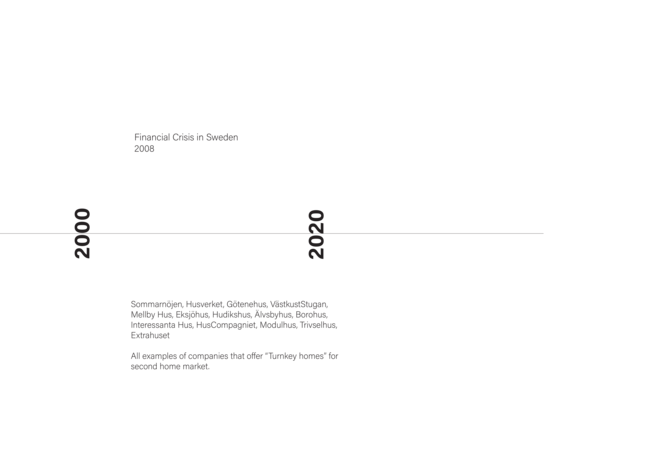

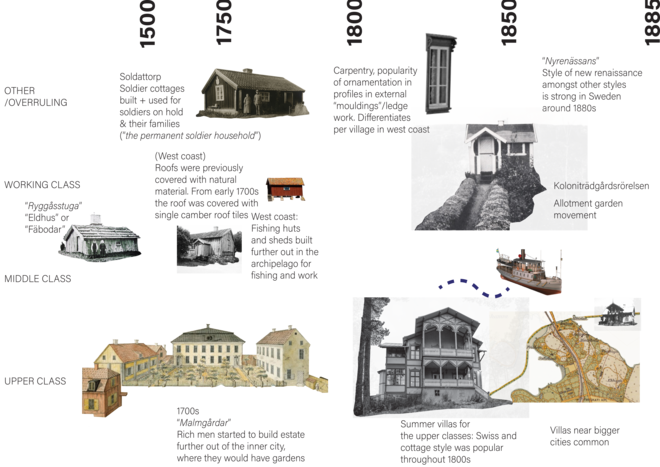

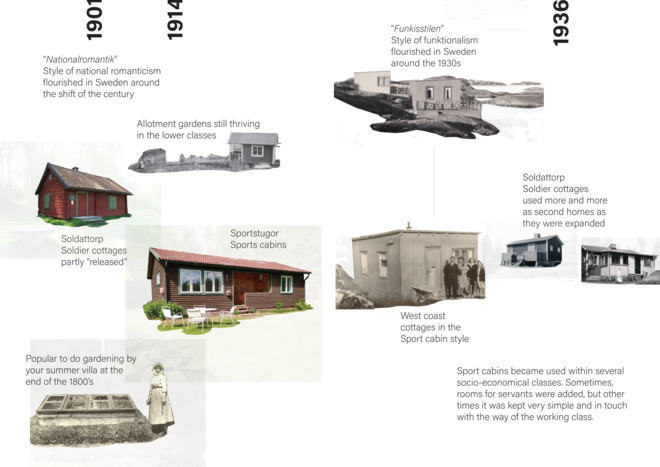

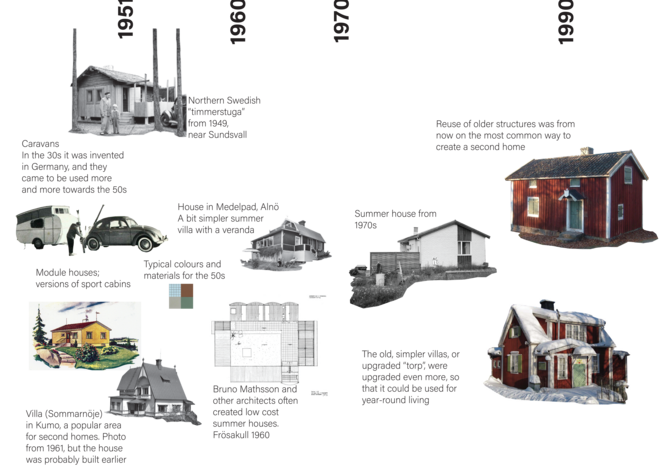

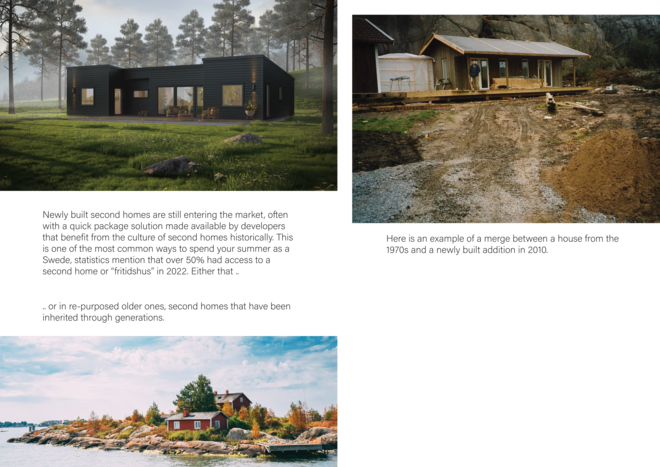

The second home; sommarstuga, hytte, sommerhus or fritidshus, is a highly common thing in the Nordic countries. Often it is connected to childhood dreams and rich summers where nature, family and certain timescales are present. This of course stems from many years of welfare and positive economic growth, mixed with geographical abundance, privilege and possibilities which are not shared all over the world. It does however exist in many other countries and areas, like the Russian Dacha, the east-Canadian chalet, the alp huts in Europe and probably lots of other typologies in more places. This project is focused on the Swedish west coast.

[[{"fid":"364637","view_mode":"top","fields":{"format":"top","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"Statistics over Sweden, density of second homes per 5x5 km2. Source: SCB.","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"Statistics over Sweden, density of second homes per 5x5 km2. Source: SCB."},"type":"media","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-top"}}]]

The history of second homes is a springboard to acknowledge a great privilege, of owning a second home and having the luxury of going elsewhere, of shifting environments, of having something so dear to you whilst it is an ownership opulence. It craves from us to have the reflection of access and immaterial accessibility - who has the choice and the circumstances to have a second home?

Who has access to a second home, and why? or: Who doesn’t - and why?

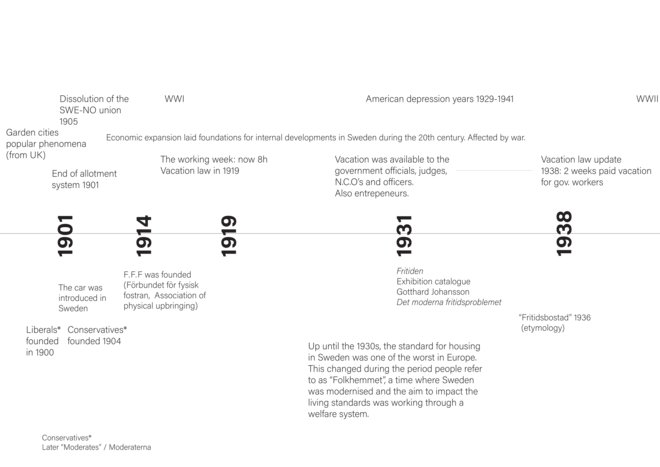

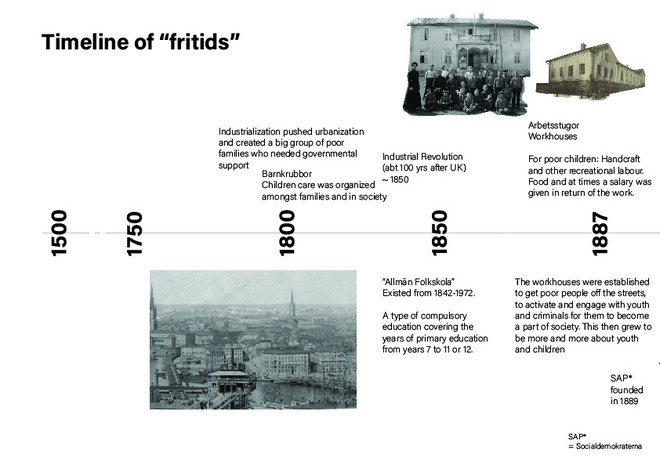

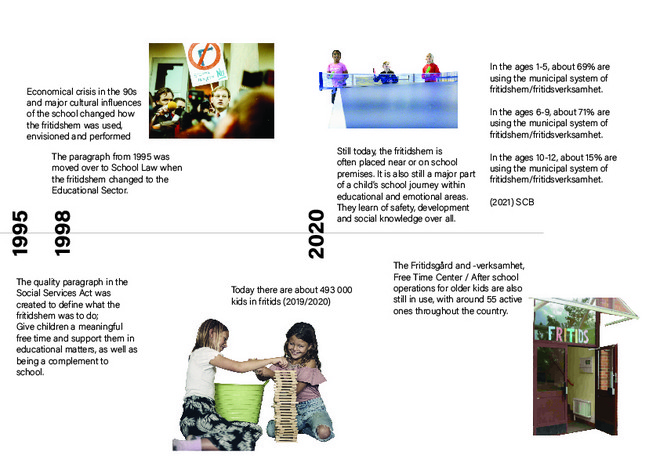

The concept of “fritids” – which roughly translated means free time, is more so relevant in the aspect of it being a space to spend the free time. Especially if a second home is not something you have the advantage of having. As a child, you may spend quite some time here when looking at the context of Sweden or the Nordic countries. SFO, fritidshem, nattis, fritidsgård, fritidsklubb, fritidsverksamhet are some versions of what may support the kids in their after-school hours, when their parents are working or away, and during holidays. The leisure-time center, fritids, has been a source of many successful stories, and has meant a great deal to culture and society overall. Many youth groups, movements and even musical bands have had their young days at an Ungdomsgård, which is what some of them were called in the 20th century (Ebba Grön, Jerry W etc.)

In Sweden, the after-school program consists of two parts. Firstly, the “fritidshem” which is for children aged 6-13, and is paid for by the parents. The school must offer a spot for all children, and there are different prices depending on occupation, income, and other parameters involved. All schools are legally bound to provide this care, and it is most commonly facilitated on school premises. From the age of 10 it is no longer demanded that “fritidshem” is available in every school. A lot of parents withdraw their kids from “fritidshem” at the age of 10 because of the payment, and sometimes also because there are free time activities for the children to attend such as football practice, music lessons, etc. Of course, this is not the case for all children, as these activities must be paid for most of the time. Therefore, the state also has economically facilitated a second part of the fritids – the “öppen fritidsverksamhet”. This is commonly known as “fritidsgård” or “fritidsklubb” in Swedish, and is what I will refer to as the after-school program in the remainder of this document. It spans from the ages of 10 up to 19 but is not as regulated as the “fritidshem”. Most commonly, the ages 13-16 are covered in these institutions. They are free of charge, and made for kids who might not have activities in their free time, either due to lack of interest, difficulties in engagement of performative tasks, and social and/or economic reasons. This kind of after-school program is therefore often visited by more troubled youth, but through the relationships made and maintained there, it is often a support in their development.

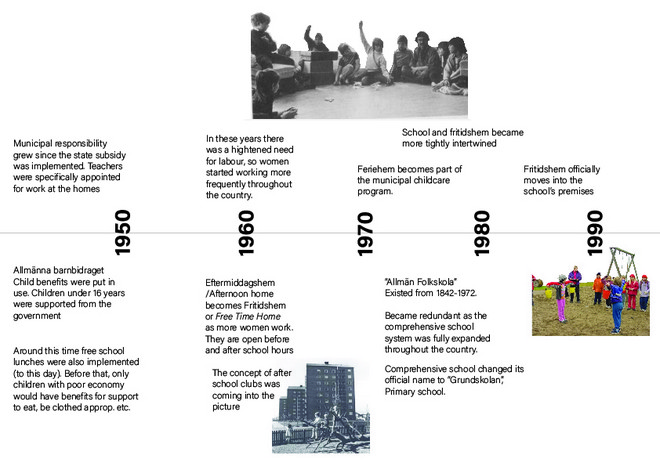

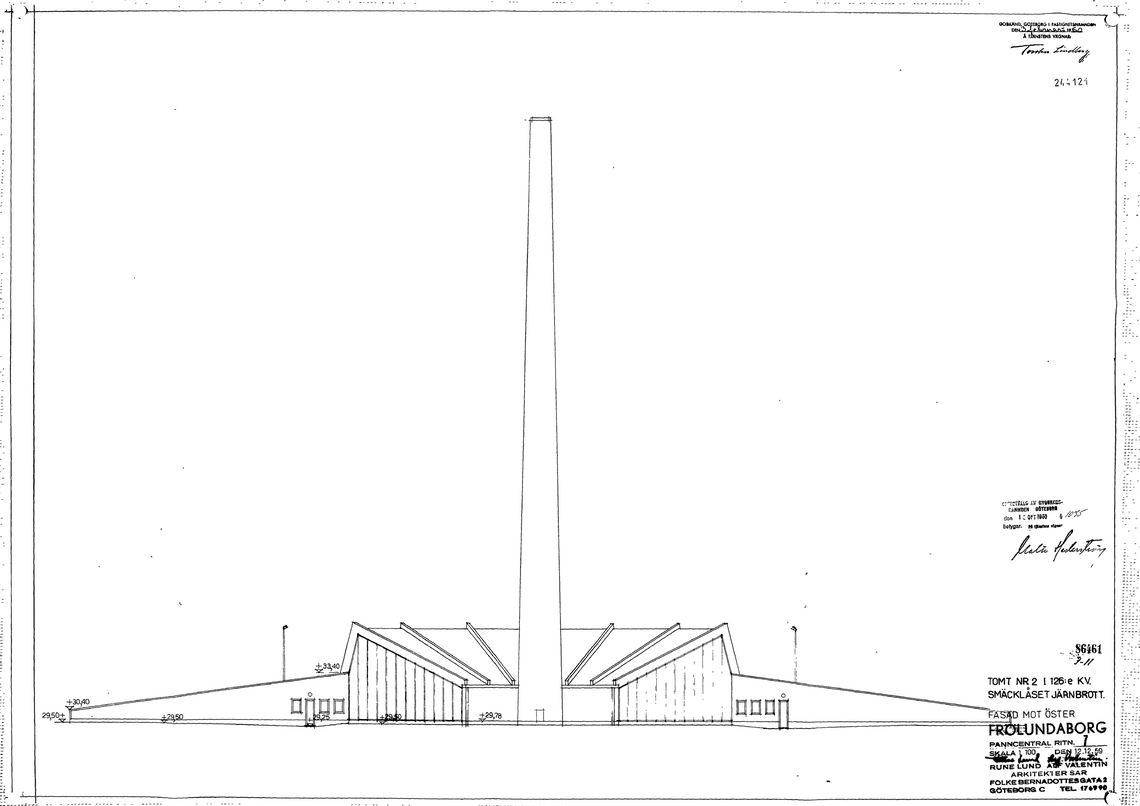

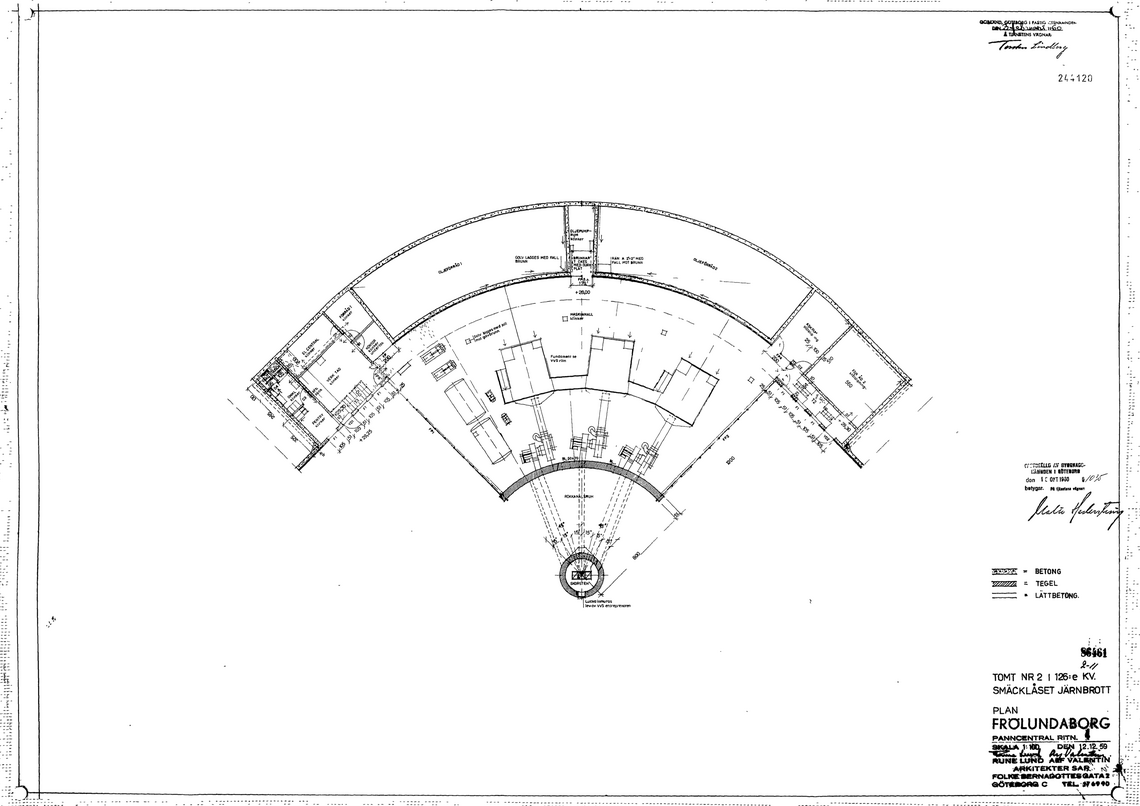

The welfare system of the 20th century has made these structures possible, where care for children is built up and supported financially through tax payments. In the same way there has been a big culture of “sommarkollo” or “skollovskollo”: a kind of summer camp which had its peak in the 1960’s and 1970’s, and has now been around for almost 150 years. Historically, these camps have been one of several ways to support similar groups of youth during longer holidays when parents needed to work and could not support their children whilst school was not active. The thesis project presented covers both the after-school program and the summer camp narrative, together with a third program: “Pannan”. It points to the word “Panncentralen” which is casually translated to boiler room/facility.

When looking both at the project as a whole, as well as the themes touched upon, the theory of de- or re-territorialization has been applied. The diagram below describes how this is done.

In the program it is covered as such:

"Critical Theory is a discipline which covers a range of concepts, one of which is deterritorialization. It can be described as the process where a social relationship, a territory, has its present arrangement and conditions revised, mutated or completely dismantled. The new pieces that come from this, are then composed into a new territory: this process in turn is called reterritorialization.

If deterritorialization, the moving of a concept from its own territory, can ignite imagination and create a platform for re-territorialization, how is this applicable to the project’s theoretical context?

I would like to see if disassembling the culture of second homes and putting it up in a new geographical context could impact the present intanglible accessibility to it. It would be placed in a new territory, where re-territorialization could develop an alternative way of enacting this experience, which then might be made accessible to new groups.

The after school program, fritidsverksamhet, is a host for the re-territorialization process, and to further challenge the structured it will on its own also be de-territorialized, taken apart and reshuffled.

It is not possible to plan these processes, but what is done is the sobreity of disassembling and reorganizing already existing concepts, bringing them together in new ways. This would be a work in progress."

For the sake of the method, to reorganize and re-iterate, I proposed a cross-contamination of functions. The suggestion is to create a fritidsverksamhet that shifts over to a summer/holiday camp, benefitting from the cross-programming, especially through their seasonal positioning. It will not shift permanently, but will in logistics be parallel to each other. To further benefit from cross-programming, there would be a second bridge. A possibility for contamination of worlds, through the pedagogical institution contrasting with a technical and industrial life of a geothermal energy facility.

The term transprogramming was coined by Bernard Tschumi as one of three options that he formulated to deal with the changing way that we see function and space, the other two being crossprogramming and disprogramming. Transprogramming involves the combination of two different programs in the same building. Regardless of the spatial and cultural incompatibilities and inconsistencies between these two programs, they are combined in the same physical object. This object therefore derives its form from the intersection of the various spatial configurations that are inherent in each program.

Tschumi was not the first to address these issues. Among the influences specifically cited in his writings is the avant-garde Situationist National movement of the late 1950’s and ‘ 60’s. The movement was largely academic, led by such figures as Guy Debord, Henri Lefevbre, and Constant Nieuwenhuis. Situationist thinking was aimed at a complete redefinition of almost all parts of life: history, theory, politics, architecture, urbanism, and art among them.

To cover the typologies and instances of second homes in the Swedish landscape, as well as the parts of history that have helped create the contemporary version of the after-school program, there has been work done on timelines covering these themes. Please peek through the gallery below to see more.

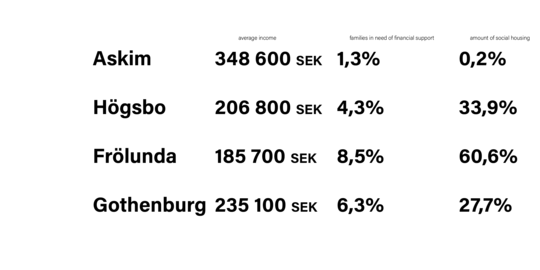

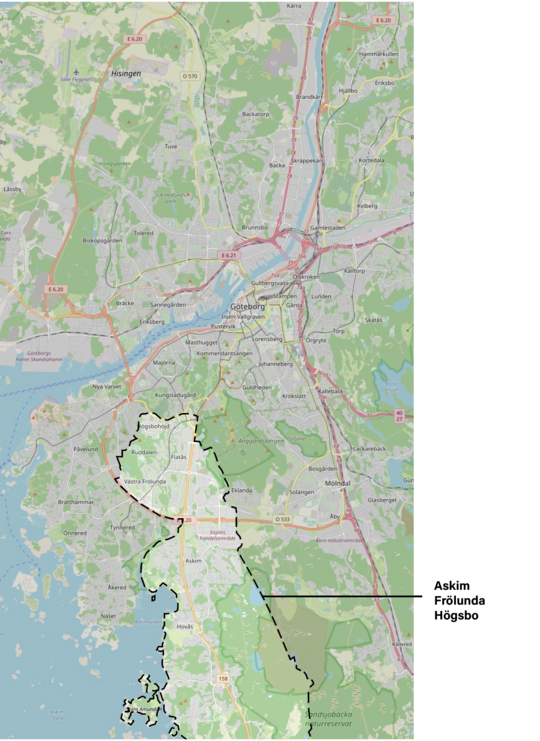

The Swedish context gives the framework of a politically introduced welfare system and a strong middle class, acting school systems and pedagogical routines. The placement is in southern Gothenburg, a place described as quite wealthy and a conservative part of the city. In contrast, the city itself has an overall rumour of being a socialist and working class-saturated place. The city is very segregated, keeping cultural and social groups apart. In 2011 the districts Frölunda-Högsbo were unified with Askim district to share one council and one budget. When looking at statistics, Högsbo has a marginal advance compared to Frölunda on parameters like employment, social housing and overall average income. Comparably, Askim is almost in double amounts in contrast to the Frölunda area. Gothenburg as a whole is statistically placed in between Högsbo and Askim.[1] Therefore, there was a big outcry of “injustice” from Askim when the original three areas were joined into one. The placement of today’s district Askim-Frölunda-Högsbo both internally and in total is relevant because of how people might move when going to work, consuming and using their context. Askim is south of both Högsbo and Frölunda, piercing through the two when moving towards the inner city, where most jobs are. Therefore, this area is interesting because it has a natural movement that can benefit the work of integration between people from within the same district but of shifting backgrounds. It is widely known that diversity and the meeting between different districts is favourable to society, economically and socially.[2][3]

[1] SCB, “Levnadsförhållanden i Sverige.”

[2] Fainstein, “Cities and Diversity.”

[3] “How Diversity Makes Us Smarter.”

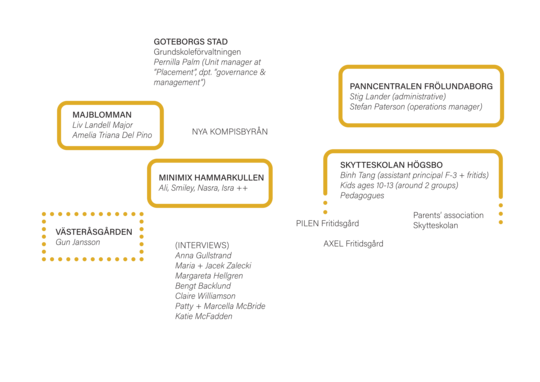

The project is a transformation of an existing building near the traffic hub Marklandsgatan in the intersection of the introduced areas.

The project outcome is the curriculum first and foremost represented through the drawing set (plan, section, isonometry), as well as the illustrations I have worked with methodically throughout the whole process. These, together with intense and wonderful interactions with stakeholders (Panncentralen Frölundaborg: Stig & Stefan, Skytteskolan: Anita, the kids & Binh, Minimix: Ali & Smiley, Majblomman: Liv L.M and so on) have been my strongest suit through it all. Please enjoy my drawings and production, and don't hesitate to message me on either my phone number, email or even Linkedin ;-) Let me know if you have questions!

Thank you for your attention.

Best,

Ada

Det Kongelige Akademi understøtter FN’s verdensmål

Siden 2017 har Det Kongelige Akademi arbejdet med FN’s verdensmål. Det afspejler sig i forskning, undervisning og afgangsprojekter. Dette projekt har forholdt sig til følgende FN-mål