knot, soil, and print: Institutions of Anarchism

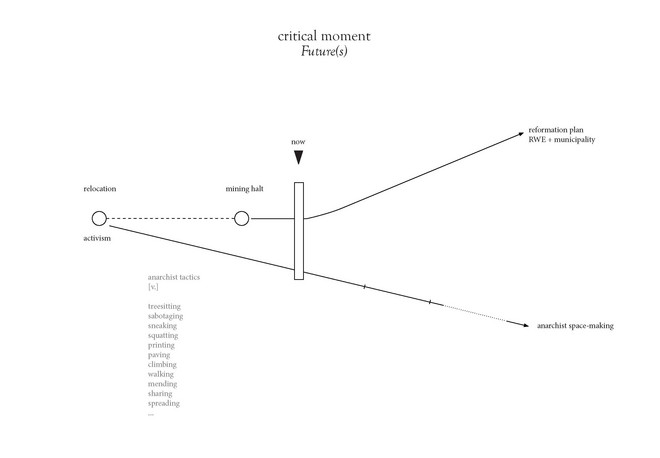

This project is firstly an inquiry into the anarchist tactics in the worlding of Hambach tree-sitting activists, and secondly an exploration of anarchist space-making by translating the tactics into an architectural proposal – the institutions of anarchism. Through fieldworks and makings, we explore how anarchism could inspire a bottom-up space-making process in the post-capitalist landscape.

knot, soil, and print: fieldwork

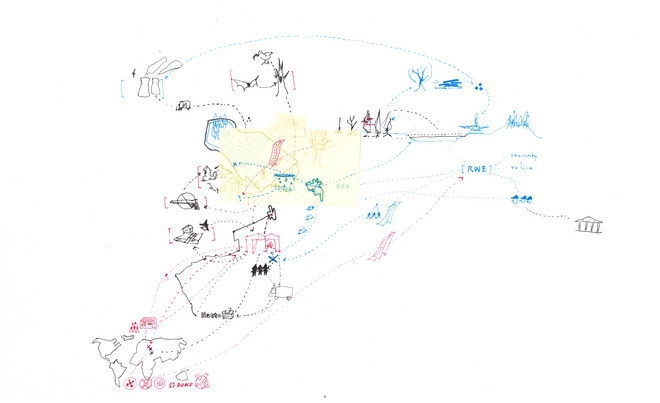

Through the fieldwork, three elements crucial in the Hambi activism emerged: the knot, the soil, and the print. We followed these elements as clues to guide us through the Hambach landscape.

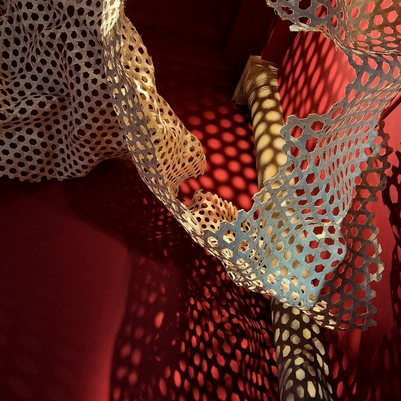

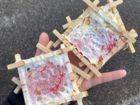

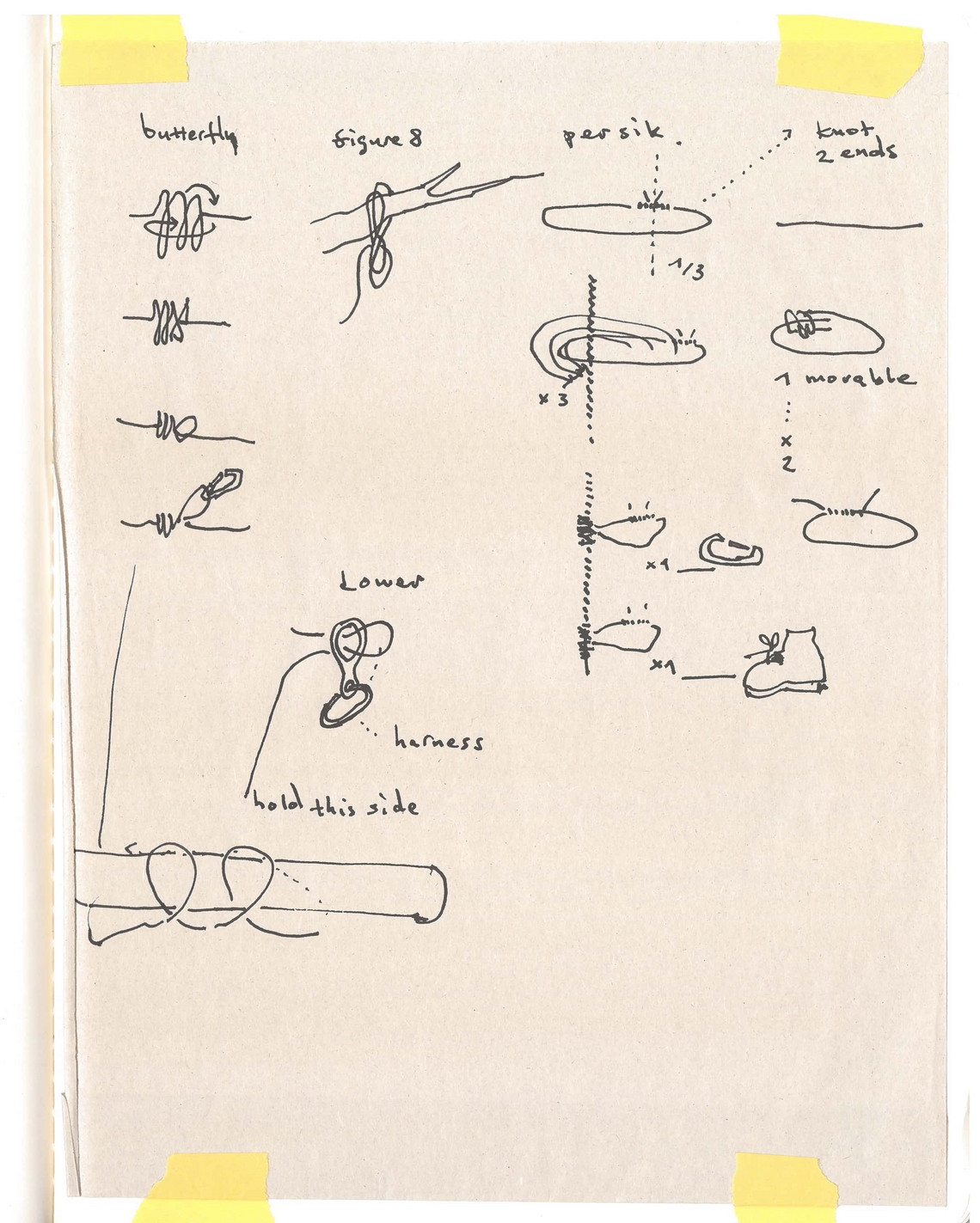

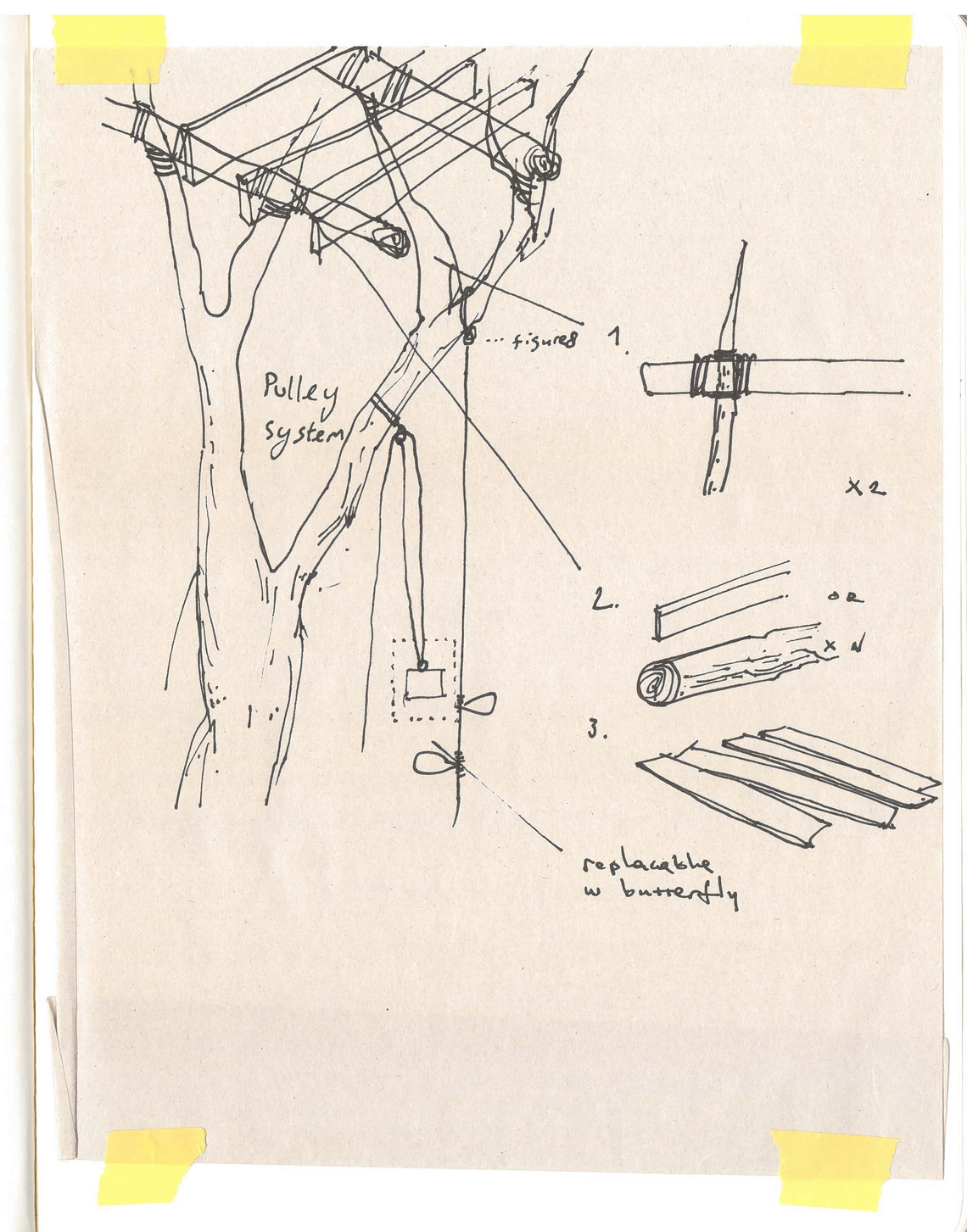

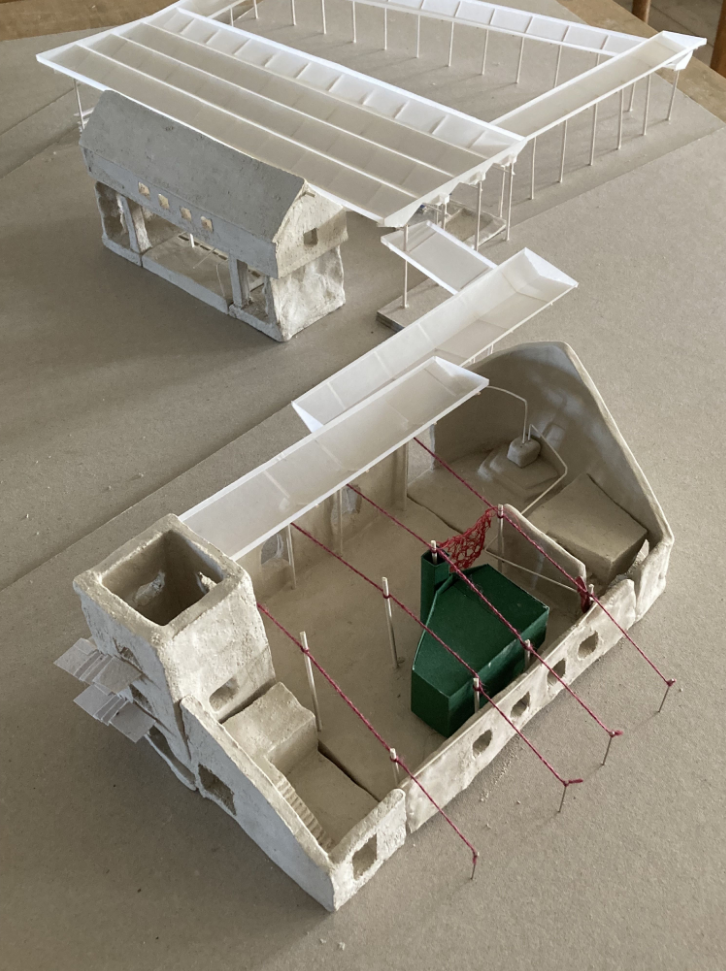

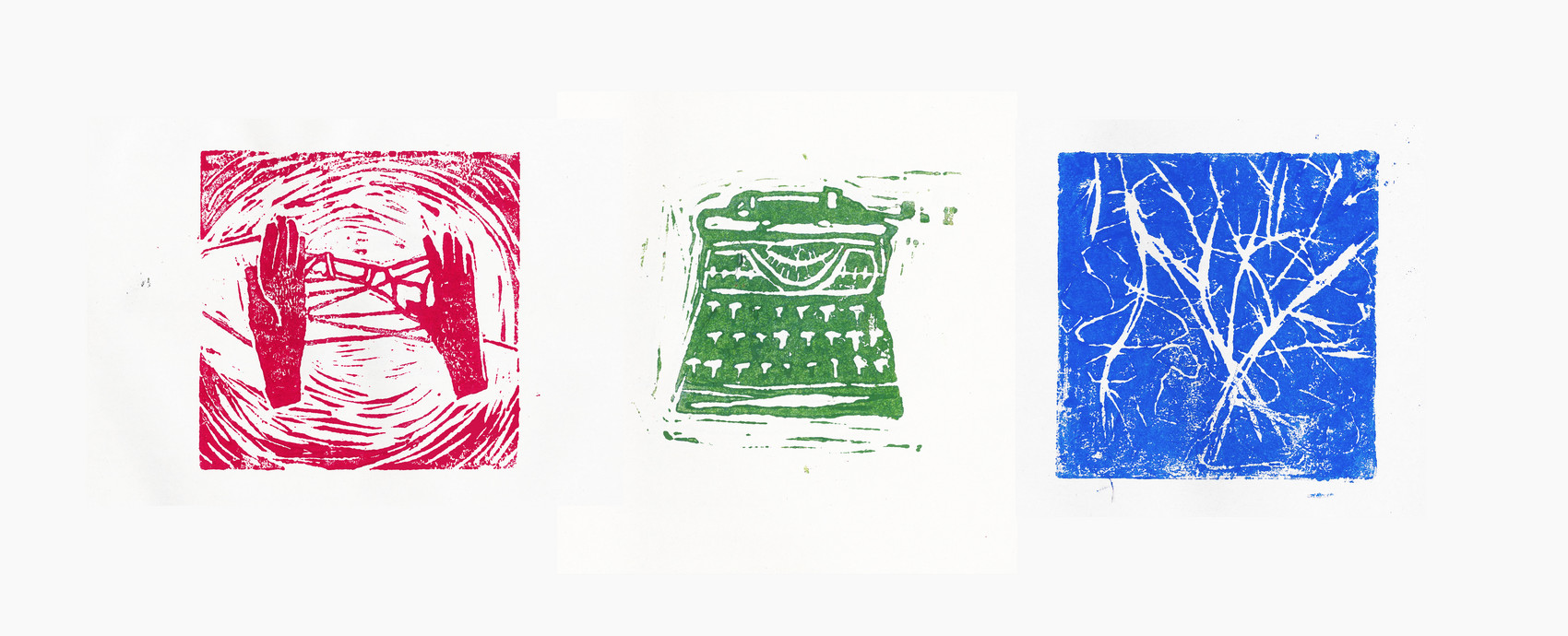

[x] Knots in Hambach are simultaneously a construction method, an embodied language, and a self-initiated infrastructure. Visible in tree climbing and tree house building, knots enable movement to previously inaccessible spaces. Extending the knot logic to a surface, the continuous knotting transforms into crocheting and weaving, which are also observed in Hambi forest.

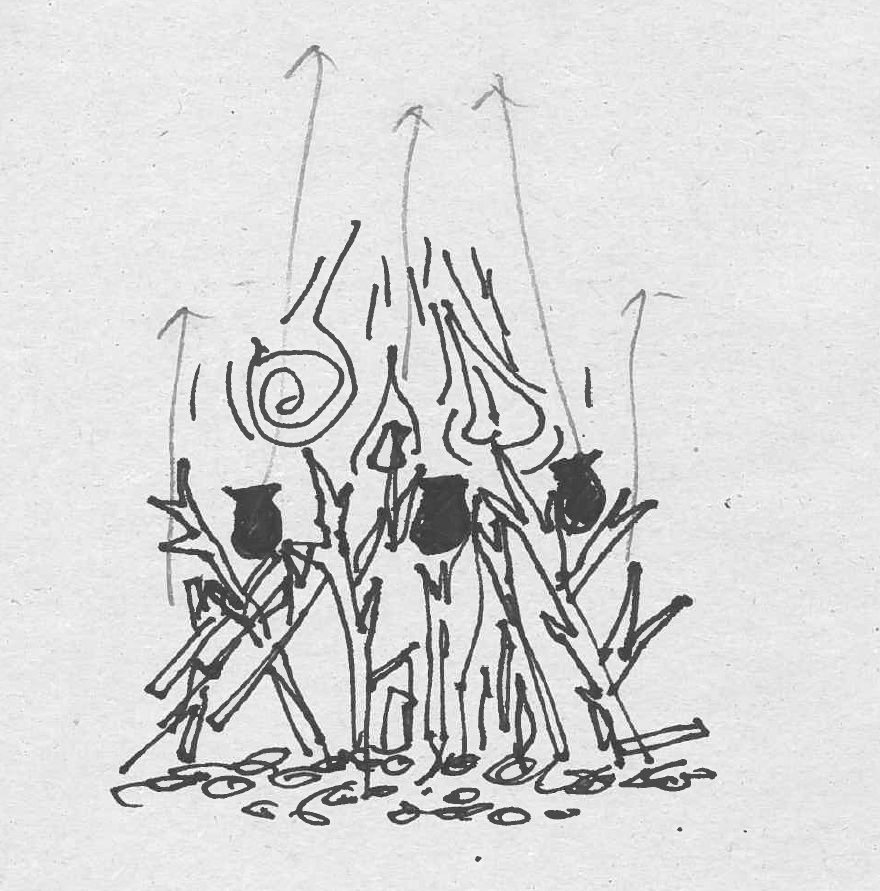

[x] Soil builds up the material life and alters territorial conditions, becomes a local handy building material, and relates to the life cycle in the forest.

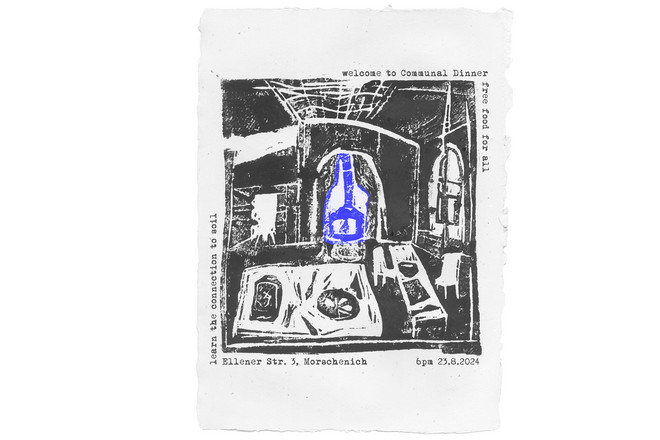

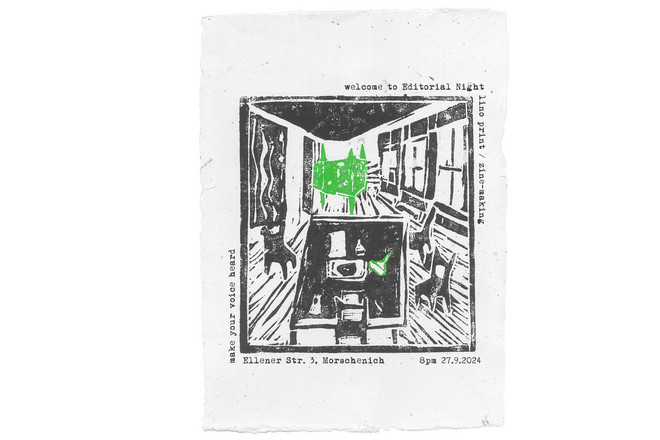

[x] Print is machine, action, and network. It spreads information outwards and makes allies on a nomadic scale, leaving traces and archiving the anarchist knowledge.

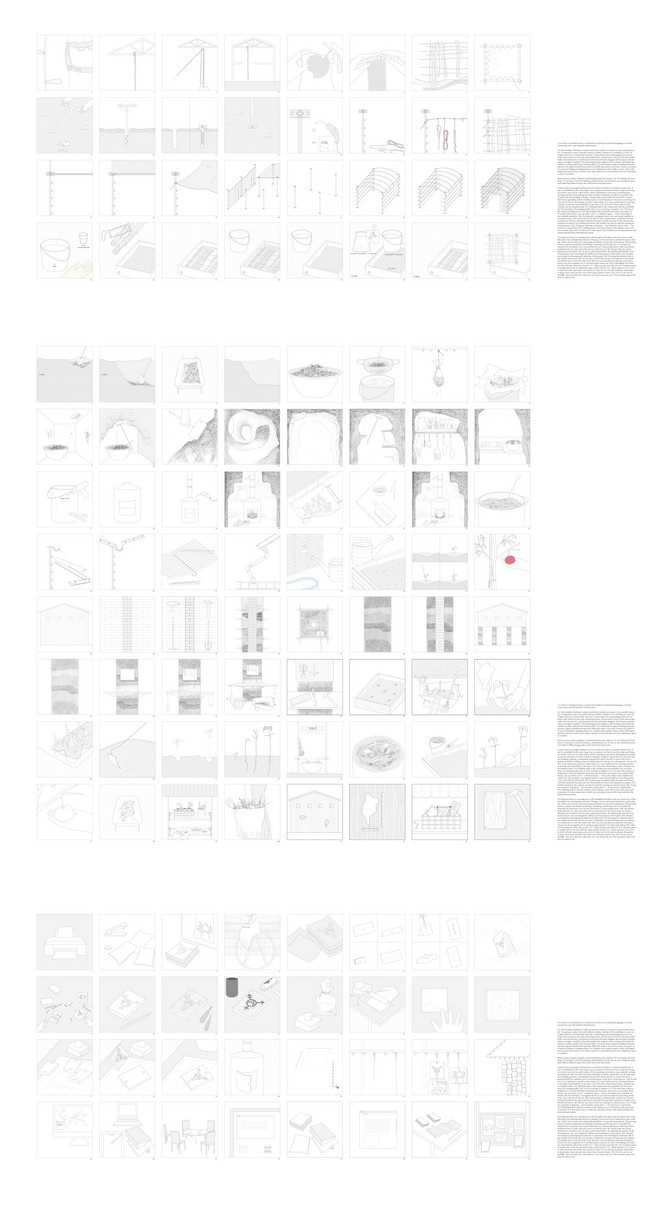

We observed, documented, practised on the knot, soil, and print during the fieldwork, and attempted to expand the scope of them by a series of material tests. We have tested knots as weaving pieces, as substrate for mycelium; soil as in clay pane; and print as in lino printing workshop and zine making.

Institution

“Anarchism is, itself, an idea, even if a very old one. It is also a project, which sets out to begin creating the institutions of a new society ‘within the shell of the old,’ to expose, subvert, and undermine structures of domination but always, while doing so, proceeding in a democratic fashion, a manner which itself demonstrates those structures are unnecessary.”

Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology (2004), David Graeber

In Graeber’s argument, there are two concepts that seem contradictory to each other appearing here: anarchism and institutions. From our fieldwork in Hambach, we realized that although anarchism is often perceived as chaos and anti-any-institutionalisation, it actually actively invents institutions, in a very different way from how governmental institutions form.

In a similar way, Natascia Tosel argues that the institution in the anarchist space “provides, rather than limitation, an invention, a positive model for action” (Tosel, Deleuze and anarchism, 2020).

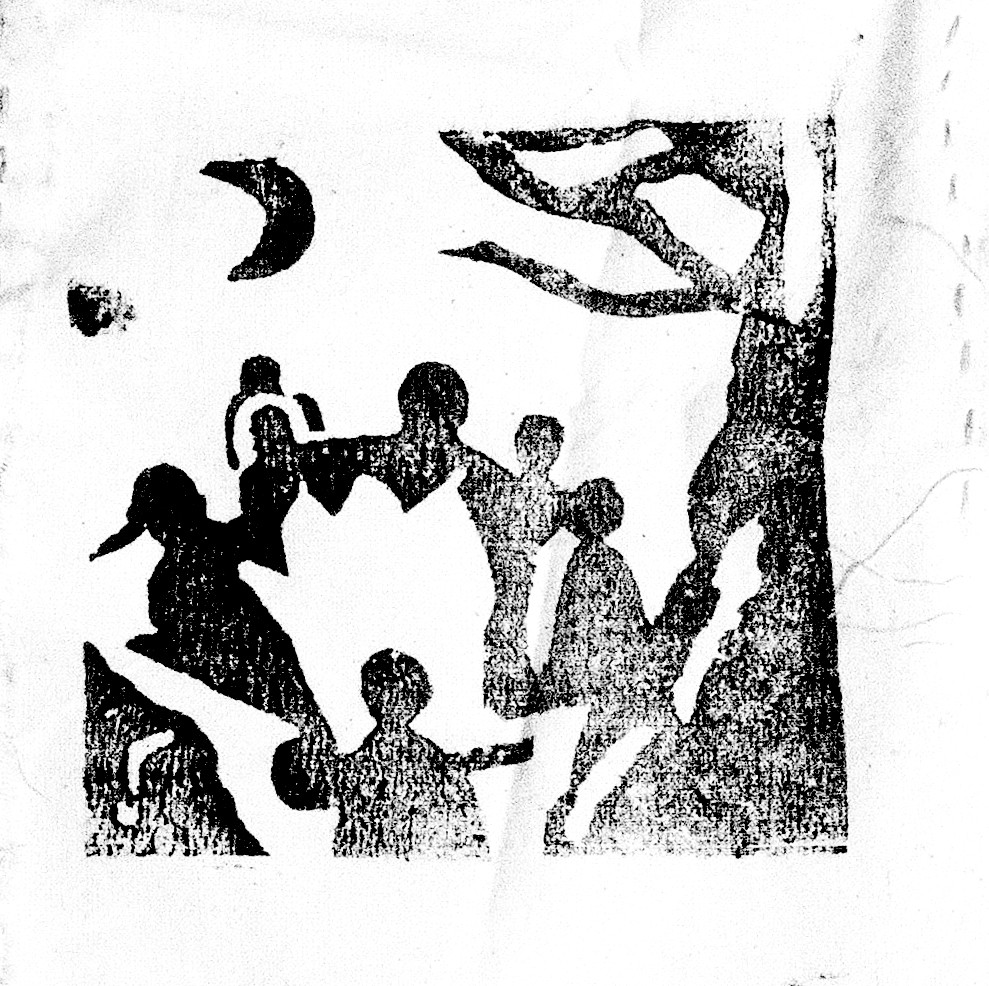

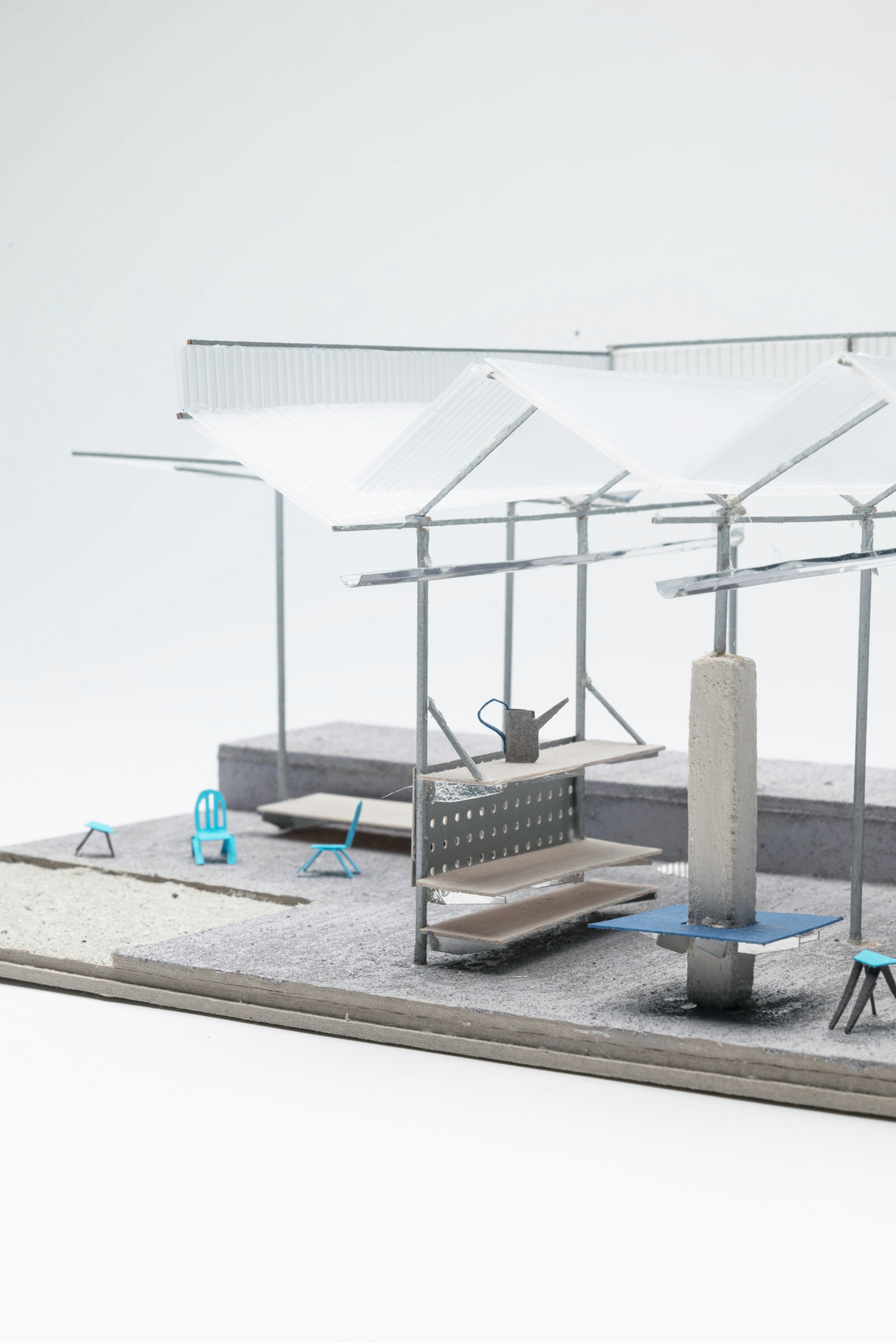

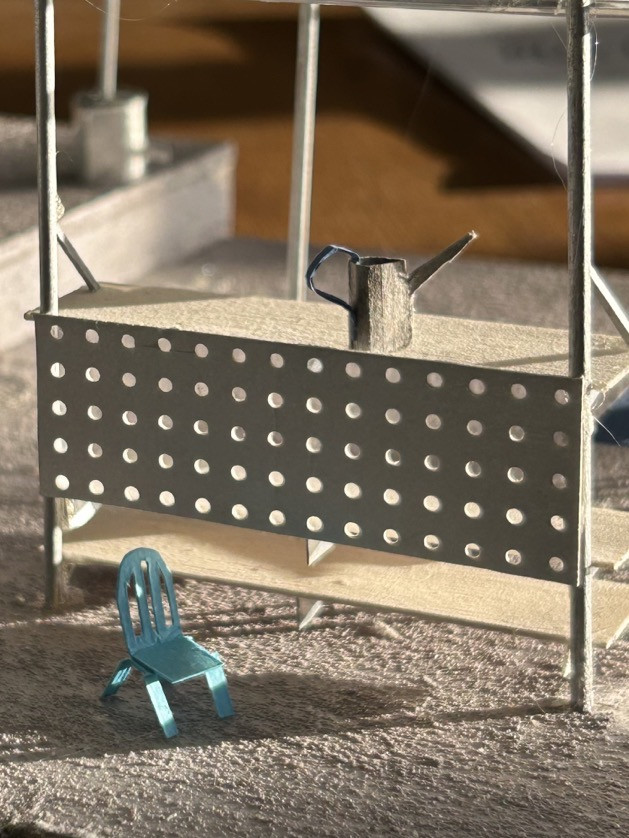

In the Hambi anarchist space, we’ve seen people inventing institutions to maintain their material and social relationships. For example, they set up a food sharing stand that shares the food with the residents nearby. There is also the “free-shop” that encourages the exchange of spare things, the rain collector that gathers water for farming and washing, the printer and the library produce and archive knowledge for the anarchist community. These inventions, functioning as the anarchist institutions, altered the anarchist space from chaos to auto-organisation, transferring the practice from temporal to durable.

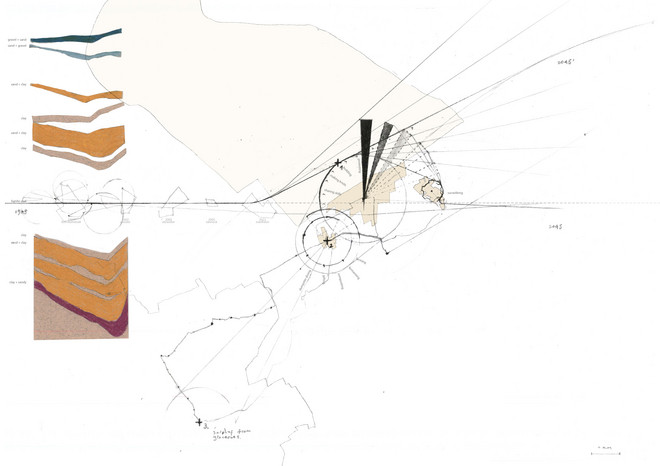

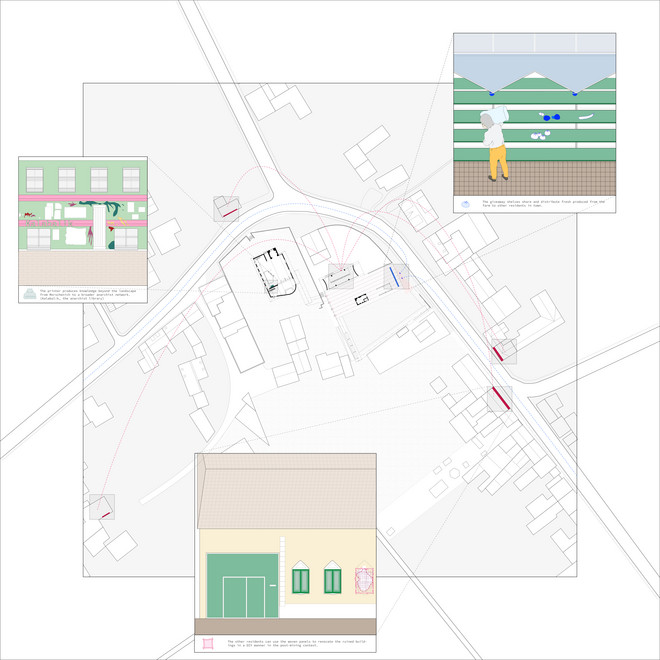

Morschenich, a village situated in the post-mining landscape next to the forest, is chosen as the project site. The social ecology around the mining pit has been affected for a century, but now with the halt of mining we are witnessing a new in-between status: places that were once evicted but in no need of tearing down anymore; places that are not fully desolate, nor are they livable; Morschenich represents quite well the situation of these places in the post-mining landscape. Many people call this evicted place a “ghost town”, but it is now still inhabited by several marginalised groups: a few residents who refused to leave during the eviction, the refugees temporally placed here by the government, and the Hambi anarchists.

Currently, as the mining stopped, the mining RWE company shifted its attention to the town, planning to transform the evicted town into a tech industry incubator. The core incentive behind this renovation plan is to seek investment and attract green business. RWE company has adopted several ways to keep the town under control: separating residents and refugees from the anarchists to prevent solidarity between the groups; having security patrolling the streets; sending social workers to persuade the anarchists to move away, etc. This strategic separation, with the deprived condition of the infrastructure, has made the resistance to the reformation plan very difficult.

Now is the critical moment where the future depends largely on the actions now. We have one dominant, profit-oriented future - that is strategically pushed forward by the power and capital of the mining company and municipality. Facing this future planning, We imagine an alternative way of making space that takes the anarchist approach, learning from their tactics and engaging other stakeholders in the town into this collective action. This alternative way of making space will inherit the anarchist tactics from forest occupation, confronting and trying to subvert the current trajectory of techno-scientific vision. It aims to occupy and maintain a public space from a bottom-up way through direct actions.

We chose to focus on Morschenich for its politically charged and in-between situation, and also for that we see hope in the anarchist basecamp, with their way of staying with the post-mining ruins.

By focusing on this, we want to explore how anarchist tactics and direct action spirit can inform a bottom-up space-making and transformation process. These two ways of reformations also represent two ways of conceptualising time: the linear temporality of RWE company that focuses on the speculation of distant future vision, and in contrast to that, a messy, layered, and reoccurring temporality of the anarchists where reproductive labor is encouraged for strengthening the community.

Program

We imagine the becoming of Institutions of anarchism in Morschenich. The institutions of anarchism emerges within the current Hambi anarchist practice, stands with the anarchist perspective and extends outwards, inviting political participation of the residents, the refugees, and others, creating public space from inside.

Through the actions of sharing, learning, building, it subverts and undermines structures of domination. It is a place that uses the anarchist self-initiated tactics to repair the wounded material and social infrastructures in Morschenich.

Through materially rebuilding ruined infrastructure, the residents and refugees are able to gain political presence, to counter the demolition plan of the RWE and the municipality, projecting direct action anarchism into their everyday practice.

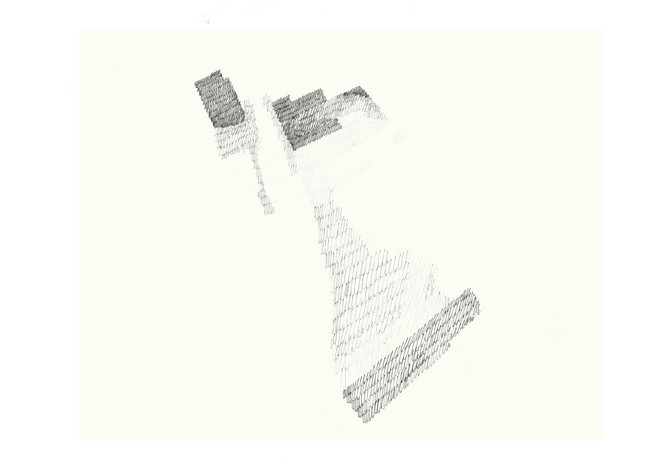

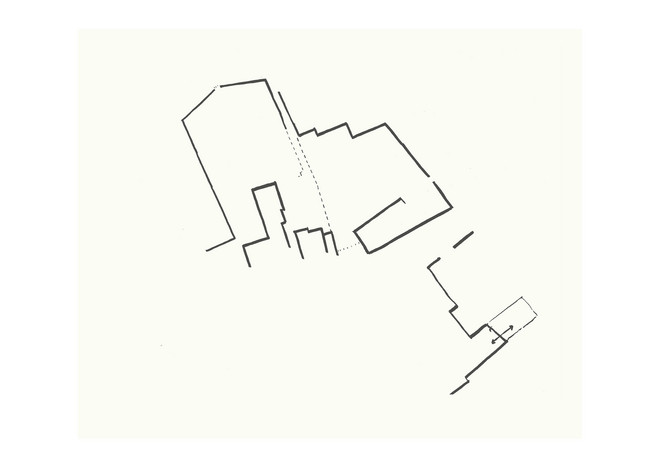

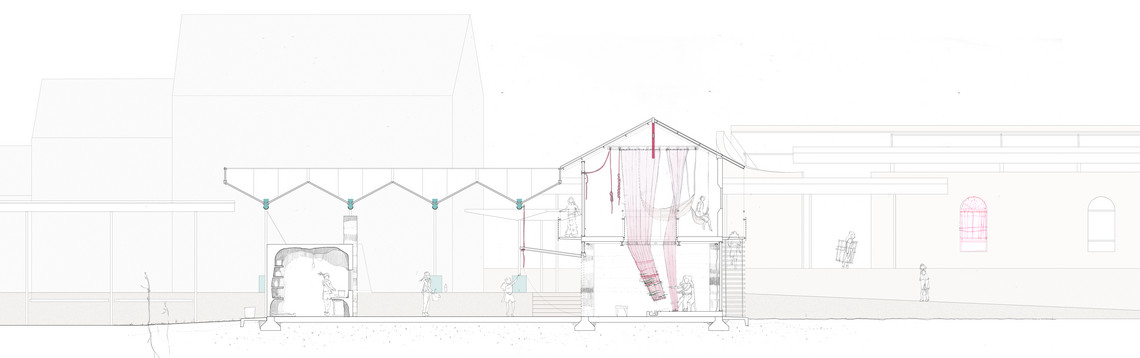

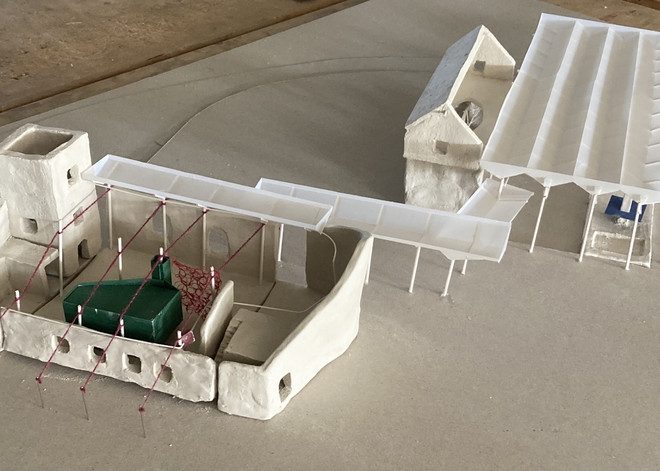

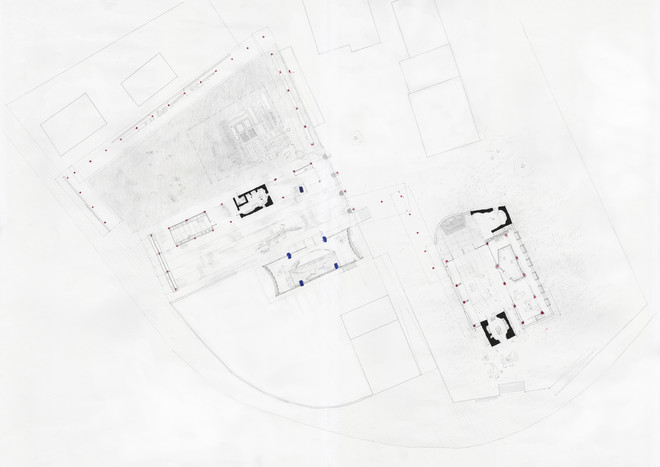

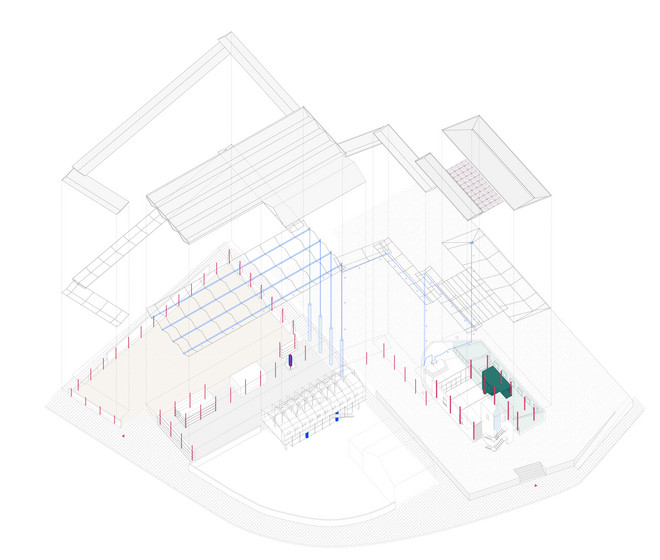

The site is situated in the centre of Morschenich, a church that was burnt down in 2023, and a farmhouse that is currently vacant.

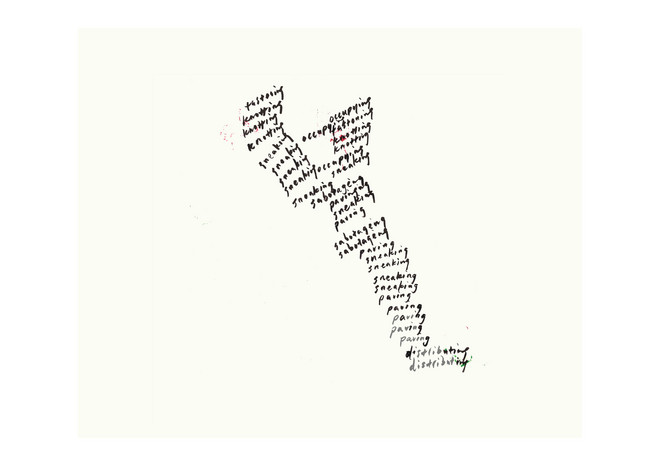

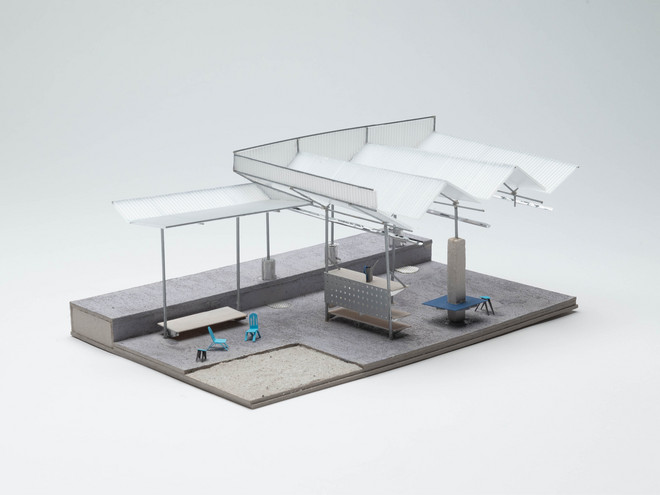

We imagine the making of the institutions of anarchism mirrors the temporal rhythm of the forest occupation. Initially, it takes direct actions, starting with a very fast-paced occupation like sneaking and squatting; later, it involves elongating it into long-term living with self-initiated institutions. The User’s Manual serves as an action toolbox for sustaining a space.

Eventually, the project evolves into a two-fold production: (1) an architectural proposal that is imagined to be both a space for gathering and a place for producing the space together, and (2) a user’s manual on how to elongate an occupation, which is formatted in a zine.

The user’s manual serves as a sharable knowledge for locals to make the space. It can also travel outwards to inform autonomous space-making in other places. The architecture itself could be seen as both an experiment to generate the tactics and an exemplary proposal resulting from actively employing the tactics.

The central space provides such platform for not only workshop and communal dining but also political discussion. To gain power for people requires direct actions, but also it requires negotiation and strategic communication with those who hold the power. So an anarchist space is never a frictionless place but a platform that invites and nurtures the voices of the minority to push forward direct democracy.

The Institutions of Anarchism started from a detail and building scale, but eventually reaches to the landscape and nomadic scale. The panels can repair the village, the giveaway shelves can make up for the ruined infrastructure, and the prints, the user's manual, will reach out to a broader community and hopefully inspire other towns that are going through a similar situation.

In a post-mining ruinous landscape, the institutions of anarchism will begin to suggest that bottom-up planning is possible, and a new form of community is possible. We wish that such a possibility can plant the seed of hope in other precarious places affected by the mining landscape.

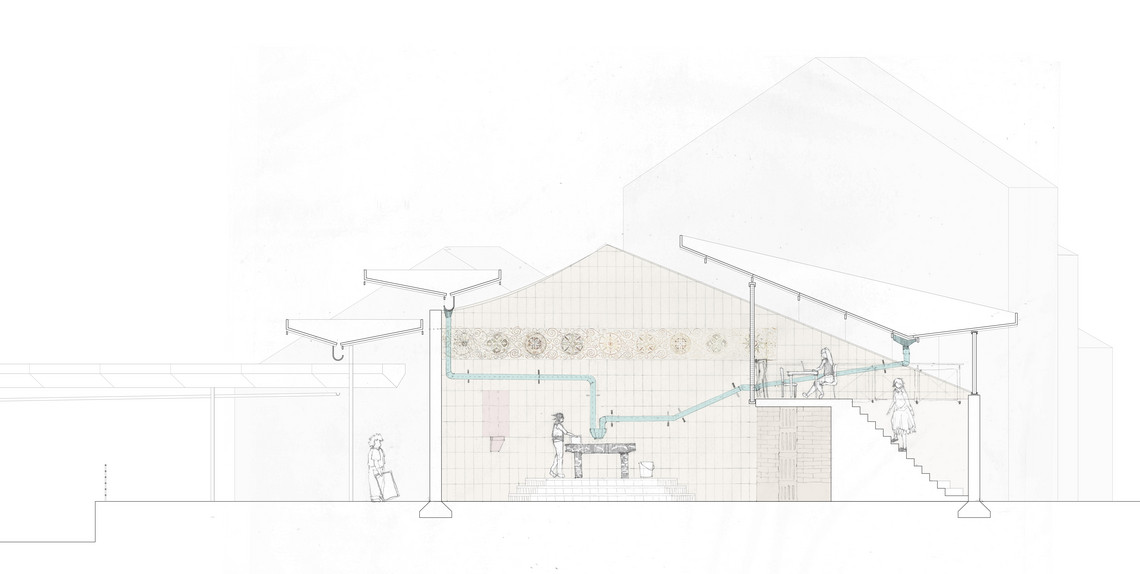

The church is transformed to a printshop and common gathering space with a kitchen; the farmhouse partially preserved its program of farming with a garden area, now equipped with water collecting roof and the farming toolbox. The other part of the farmhouse is transformed into a communal weaving house and a shelter in the attic. The entrance to the farmhouse area and the church is transformed into a free exchange and give-away shelf to invites broader participation.

Through the repairing actions, the Institutions of Anarchism will slowly take its shape. The space will be filled with objects that afford the programs of knot, soil, and print. It has then reached a phase when it can open up and inspire participation in the town. In between the architectural programs, various flows co-exist -- the ones of producing, gathering, making, discussing, and exchanging.

Fictional events are used as a way to develop the spatial experience and sequence. Institutions of Anarchism offer frameworks that support different levels of engagement from stakeholders: one can participate in the production of space through weaving, farming, and making clay, etc.; one can also just take the extra veggies left at the give-away shelves.

Det Kongelige Akademi understøtter FN’s verdensmål

Siden 2017 har Det Kongelige Akademi arbejdet med FN’s verdensmål. Det afspejler sig i forskning, undervisning og afgangsprojekter. Dette projekt har forholdt sig til følgende FN-mål